The ECM Revelation came out last year and its changes will be included in the new UBS6/NA29. It’s the newest ECM volume to affect these hand editions. Having now spent some time with the edition, and having gone through all the listed changes, I thought I would give a brief report on them for the benefit of those who don’t have access to the print edition.

In all, the edition made 84 changes to the text of NA28 and now has 106 places with a split guiding line. These are places where the editors couldn’t decide between two readings (it is always two) and they are further marked by a diamond in the ECM and in the UBS/NA editions.

You could roughly compare this to the 35 places in NA28 that used square brackets to mark text the editors weren’t completely convinced was original. In 9 places, the ECM has a split line that matches bracketed text from NA28. In 8 places they adopted the text in brackets (now without brackets) while in 15 places, they now prefer the omission of the bracketed text. (NB: the ECM list of textual changes misses the bracket in Rev 12.12/5.)

All this means that there is quite a bit more editorial uncertainty in the ECM Revelation than there is in the NA28. Most of the split lines are not of great exegetical import. Sometimes you look at the two readings and wonder why the decision was so hard. It could be something about Revelation or could it be a result of the Rev editorial board being split between two institutions. I don’t know.

One thing that is certainly more robust in this volume is the textual commentary. It runs to over 170 pages! (All in German.) Some discussions span four or five pages. One new feature is that the comments are given labels to mark whether the variation is important for the printed history of Revelation, for the style of Revelation, its textual history, etc. The “SEM” label marks 48 variants of “semantic relevance.” Here are their addresses and the readings in question per the commentary:

- 1,3/4-12 a/b

- 1,5/48-52 a/d

- 1,13/12-16 a/b

- 1,15/20 a/c

- 2,7/52-54 a/b

- 2,9/34-38 a, f

- 2,13/48 a/d

- 2,20/17 a/b

- 3,14/44 a/b

- 4,3/22 a/b

- 4,3/30—1,4/2 a/g

- 4,11/55 a/b

- 5,10/22 a/b

- 6,8/40-42 a/c

- 6,9/47 a/b

- 6,11/32 a/b

- 6,14/14 a/b

- 6,17/18 a/b

- 9,4/38-40 a/an

- 11,4/10 a/b

- 11,12/4 a/b

- 11,16/12-20 a/b

- 12,2/9 a/b

- 12,18/4 a/b

- 13,3/38-44 a/b/e

- 13,7/2-22 a/g

- 13,8/6 a/b

- 13,10/6-10 a/c/f

- 13,10/20-30 a/c

- 13,18/44—48 a bis h

- 14,4/48 a/b

- 14,13/32 a/b

- 14,14/22-28 a/c

- 14,19/44-54 a

- 15,3/72 a/b

- 15,6/30-32

- 16,5/18-32 a/c/g

- 17,5/30 a/b

- 18,2/32-54 a/b/o

- 19,6/48 a/b

- 19,13/8 a/b

- 20,5/1 a/c

- 20,8/26-32 a/b

- 21,3/46 a/b

- 21,6/8-10 a/e

- 22,14/6-12 a/b

- 22,21/14-18 a/f

- 22,21/20 a/c

| Ref. | Change | Reading(s) | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rev 1.5 | Split line | λύσαντι / λούσαντι* | λούσαντι may reflect early baptismal theology |

| Rev 1.13 | New reading | ὅμοιον ὑιῷ ἀνθρώπου* | Relevant to Christology [I’m not sure I get this one] |

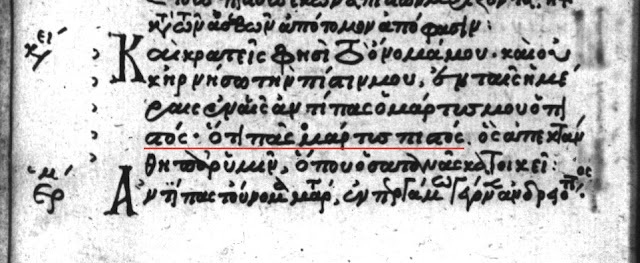

| Rev 2.13 | Split line | ἀντίπας* / ἀντεῖπας | Is it a personal name (Antipas) or a verb? The former has dominated translations in the past. (NB: ECM Mark and Rev do not capitalize proper names.) |

| Rev 6.17 | New reading | αὐτοῦ* | Relevant to Christology since it transfers the day of wrath to Jesus [seems like it does that with the old reading too though] |

| Rev 12.2 | New Reading | Omit καί* | May impact the interpretation of the woman who gives birth [not sure I understand this] |

| Rev 12.18 | Split line | ἐστάθη / ἐστάθην* | Changes who is standing on the shore, John or the dragon |

| Rev 13.10 | New reading | εἴ τις εἰς αἰχμαλωσίαν ὑπάγει, εἴ τις ἐν μαχαίρᾳ ἀποκτενεῖ, δεῖ αὐτὸν ἐν μαχαίρᾳ ἀποκτανθῆναι, | A number of options are possible with this new reading. [I think this one is pretty noteworthy.] |

| Rev 18.3 | New reading | πεπτώκασιν* | People have “fallen” rather than “drunk” |

| Rev 20.5 | New reading | Omit οἱ λοιποὶ τῶν νεκρῶν οὐκ ἔζησαν ἄχρι τελεσθῇ τὰ χίλια ἔτη. | A key line about the millennium is omitted [This may be the most significant change to my mind as it removes what has proven to be a very difficult phrase for Amillennialism] |

| Rev 21.3 | Split line | λαοί / λαός* | How many people groups does God dwell with in the New Jerusalem? One, or more? |

| Rev 21.6 | New reading | γέγονα ἐγώ | Introduces an element of “becoming” into God’s self-description [part of the commentary on this change is quite loaded theologically, and I’m a bit more cautious on its significance] |

| Rev 22.21 | New reading | πάντων τῶν ἁγίων. Ἀμήν.* | The request for grace is more strongly related to the church than in NA28 which just reads πάντων here [I agree] |