I learned some good news by way of Ian Mills on Twitter today. The British Library has now digitized Add MS 14451, better known as the Curetonian Syriac Gospels. There are a handful of leaves in other places as well (see here). The images from the BL are listed as in the public domain.

Showing posts with label Syriac. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Syriac. Show all posts

Friday, June 30, 2023

Wednesday, September 18, 2019

Handwritten-Text Recognition (HTR) for Syriac Manuscripts

The Beth Mardutho Facebook pages just announced a major development in the quest to use OCR (optical character recognition) technology for manuscripts. Calling it Handwritten-Text Recognition (HTR), they say they have it working for Syriac manuscripts. I know others have tried this for Greek for years and have run into trouble. We can hope the lessons learned here for Syriac can be passed on and used on Greek. If anyone has more details, please share.

Congratulations to the team!

Congratulations to the team!

Tuesday, July 18, 2017

Corpus of Christian Palestinian Aramaic online

NYU’s Ancient World Digital Library has the Corpus of Christian Palestinian Aramaic now online for free. This includes both volumes of the Christian Palestinian Aramaic New Testament Version from the Early Period by Christa Müller-Kessler as well as the Christian Palestinian Aramaic Old Testament and Apocrypha Version from the Early Period by Müller-Kessler and Michael Sokoloff.

NYU’s Ancient World Digital Library has the Corpus of Christian Palestinian Aramaic now online for free. This includes both volumes of the Christian Palestinian Aramaic New Testament Version from the Early Period by Christa Müller-Kessler as well as the Christian Palestinian Aramaic Old Testament and Apocrypha Version from the Early Period by Müller-Kessler and Michael Sokoloff.Also, don’t miss their papyrology section whcin includes the Chester Beatty Biblical papyri IV and V by Pietersma.

HT: Morgan Reed

Monday, March 13, 2017

On the Origin of the Pericope Adulterae in the Syriac NT

Here is an interesting detail about the origin of John 7.53-8.11 in the Syriac tradition. Apparently, in the excellent Mingana collection at the University of Birmingham, there is a “handsome and sumptuous” manuscript containing the New Testament and a number of other treatises. So says A. Mingana in his Catalogue (vol. 1, col. 863). One important feature of this manuscript that Mingana reports is this:

The Syriac can be translated as follows:

This story (ܣܘܢܬܟܣܝܣ = σύνταξις) is not found in all manuscripts. But Abba Mar Paule found it in one of the Alexandrian manuscripts and translated it into Syriac as written here from the Gospel of John.From this, J. de Zwaan, writing in 1958, draws this conclusion:

Paul of Tella, who was the leading spirit in the translation of the Hexaplaric O.T. by order of Athanasius I, and under whose auspices Thomas of Harkel laboured on the N.T. at the same time and the same place, viz. the Enaton-monastery near Alexandria (615-617), is, therefore, responsible for the introduction of John vii.53-viii.11 in MSS. of the Syriac N.T.We know that in most of the NT, Thomas actually used a nearly Byzantine text and in the Catholic Epistles he used something more distinctive, a possible precursor to the Byzantine text (so K. Wachtel). Where Thomas gave “Western” readings, so far as I understand it, is primarily in the margin in Acts.

This is interesting as it confirms the hypothesis that on Paul’s initiative the Harklean enterprise (whatever it has been: translation, revision, collation or mere annotating) was completed.

And this is important as it adds probability to the surmise that Thomas’ work should be considered as analogous to the O.T. enterprise. For textual criticism e.g. the question, whether ‘Western’ copies could be present in the viith century in Alexandria and be still valued there by experts as authoritative, this point is very important.

So I’m not convinced with Zwaan that this remark in Mingana Syr 480 shows that the “Western” text was valued in the 7th century in Alexandria. But it is still significant if Zwaan is right that this confirms Paul of Tella’s involvement in both the Syro-hexapla and the Harklean NT and that he is somehow responsible for the inclusion of the Pericope Adulterae in the latter.

You can find this and more discussed in Chris Keith’s excellent book on the Pericope Adulterae. For more on the manuscript sources, see Gwynn.

* * *

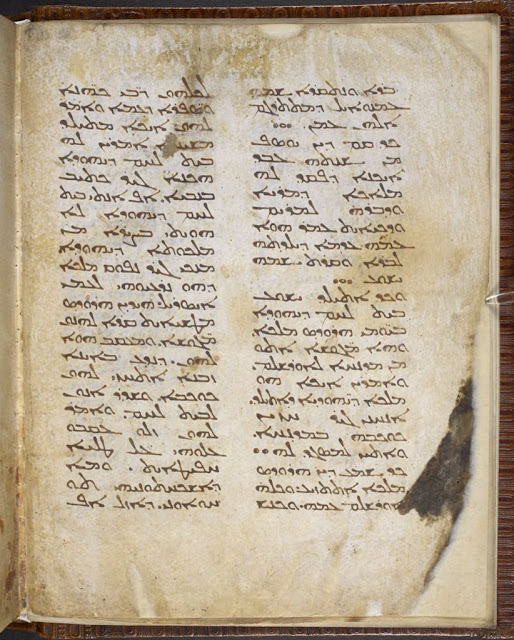

For more on the PA in Syriac and Arabic, see Adam McCollum’s blog post on a 17th cent. Garshuni lectionary which has the following note pictured below:

Know, dear reader, that this pericope [pāsoqā] is lacking in our Syriac copy [lit. the copy of us Syriac people], but we have seen it among the Latins [r(h)omāyē], and we have translated it into our Syriac language and into Arabic. Pray for the poor scribe!

|

| Marginal note in CCM 64, f. 79r, (17th cent.) explaining the origin of the Pericope Adulterae. |

Friday, March 03, 2017

Lund on Ezekiel in the Antioch Bible (Peshitta)

In RBL, Jerome Lund reviews Gillian Greenberg and Donald M. Walter, trans. Ezekiel according to the Syriac Peshitta Version with English Translation (Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias, 2015).

In RBL, Jerome Lund reviews Gillian Greenberg and Donald M. Walter, trans. Ezekiel according to the Syriac Peshitta Version with English Translation (Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias, 2015).After two pages of suggested improvements and corrections, he concludes:

Every researcher in Syriac Ezekiel will appreciate this fully vocalized text and translation. It is useful in learning Syriac and in understanding forms that might at first blush be allusive if left unvocalized. However, textual critics of the Hebrew Bible should not use this text independently of the Leiden edition.I would think the same could be applied to the other OT volumes as well. The best place for TC is the Leiden edition but the Antioch volumes can be helpful.

Friday, November 18, 2016

Le Nouveau Testament en syriaque Conference

Obviously this is too late for anyone wanting to attend, but the Society for the Study of Syriac organizes a “round table” every year and today they are meeting on the topic of the Syriac New Testament. The papers should be published in the accompanying series by Geuthner next year which I look forward to. I should note that ETC contributor, Jean-Louis Simonet, is giving a paper. Here is the full program:

Obviously this is too late for anyone wanting to attend, but the Society for the Study of Syriac organizes a “round table” every year and today they are meeting on the topic of the Syriac New Testament. The papers should be published in the accompanying series by Geuthner next year which I look forward to. I should note that ETC contributor, Jean-Louis Simonet, is giving a paper. Here is the full program:- David Phillips (Université catholique de Louvain, Louvain-la-Neuve)

« Les canons des Nouveaux Testaments en syriaque » - David Taylor (University of Oxford)

« L’Apocalypse de Jean en syriaque : des origines à Diamper » - Jan Joosten (University of Oxford)

« Le Diatessaron syriaque » - Jean-Claude Haelewyck (FNRS et Université catholique de Louvain,

Louvain-la-Neuve)

« Les vieilles versions syriaques des évangiles (sinaïtique et curetonienne) » - Andreas Juckel (Institut für Neutestamentliche Textforschung, Münster)

« The New Testament Peshitta (Corpus Paulinum) : History of the Text and History of the Transmission » - Jonathan Loopstra (University of Northwestern, St. Paul, MN)

« Le Nouveau Testament dans les manuscrits syriaques massorétiques : Où en sommes-nous ? » - Gerard Rouwhorst (Tilburg University)

« La lecture liturgique du Nouveau Testament dans les Églises syriaques » - Dominique Gonnet (HiSoMa – Sources Chrétiennes, Lyon)

« Les citations patristiques syriaques » - Jean-Louis Simonet (Université catholique de Louvain, Louvain-la-Neuve)

« Vetus Syra – arménien : les citations des Actes » - Eva Balicka-Witakowska (Uppsala University)

« Artistic Means in the Syriac New Testament Manuscripts » - Robert Wilkinson (Valley House, Temple Cloud, Somerset)

« Printed Editions of the Peshitta New Testament »

Friday, August 05, 2016

Three Interesting Variants at Rev. 2.13 Not in Nestle

While doing some sermon prep last week I came across some interesting variants in Rev. 2.13. The NA28 reads:

Others have followed Lachmann’s conjecture of Ἀντιπᾶ (the “proper” genitive of the name) suggesting that the sigma arose from dittography involving the article: αντιπα ο μαρτυϲ → αντιπαο ο μαρτυϲ → αντιπαϲ ο μαρτυϲ. That is one too many steps for my liking though.

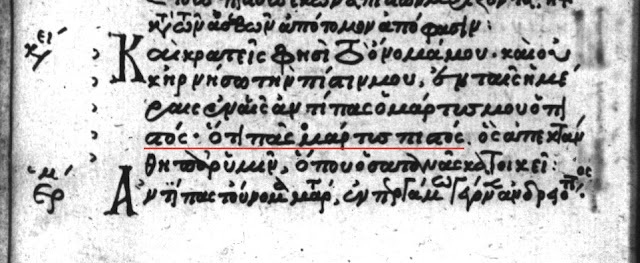

Where things get more interesting is in the Syriac. Here is what we find in the British and Foreign Bible Society (BFBS) edition which is also the basis for the recent Gorgias edition. I’ve highlighted the main differences with the Greek:

The first variant has a good explanation in that Ἀντιπᾶς is sometimes spelled αντειπας and this could be read as an Aorist form of ἀντιλέγω. Hence we get ܚܪܐ in Syriac which means “resist, dispute, contend,” etc. in the ethpeal. Tischendorf tries to explain the Syriac as a translator’s failed attempt to render the name. But explaining it as a different way to read the Greek is much more viable especially because Hoskier lists several Greek minuscules that seem to accent it as the verb (ἀντεἶπας rather than ἀντειπᾶς).

The third variant, the omission of the last phrase, is a bit easier to explain in Syriac than in Greek. In Syriac, it looks like a case of homoioteleuton involving ܐܠܐ at the beginning of v. 14. The phrase is included in the Harklean Syriac manuscripts, so, apparently, it didn’t last long. It’s only attested by two minuscules in Greek perhaps just by accident.

The second variant, the addition, is the most surprising of the three. It is also not unique to the Syriac, being found in over a dozen Greek minuscules. This suggests that the Syriac is not innovating but rather reflecting its Greek Vorlage. In his edition, Gwynn argues the same but still calls the longer reading an “interpolation.” What he doesn’t mention but should have is that its omission has an obvious explanation by way of homoioteleution, the scribe’s eye jumping from πιστός to πιστός (cf. GA 2028).

What’s important is that the Syriac shows that this reading has much earlier support than the Greek evidence alone would suggest. It goes back at least to AD 616 when the Harklean Syriac was completed and probably earlier since the Crawford MS (the basis for the BFBS and Gorgias editions) likely predates the Harklean. This is thus a good example of late Greek manuscripts preserving much earlier readings. It also illustrates the benefit of keeping an eye on the versions.

None of this made it into the sermon, you’ll be relieved to know. But I wonder if some of these readings shouldn’t make it into the Nestle apparatus. The longer reading in particular belongs there not only for its exegetical significance, but because, at least transcriptionally, it can explain the shorter reading.

οἶδα ποῦ κατοικεῖς, ὅπου ὁ θρόνος τοῦ σατανᾶ, καὶ κρατεῖς τὸ ὄνομά μου καὶ οὐκ ἠρνήσω τὴν πίστιν μου καὶ ἐν ταῖς ἡμέραις Ἀντιπᾶς ὁ μάρτυς μου ὁ πιστός μου, ὃς ἀπεκτάνθη παρʼ ὑμῖν, ὅπου ὁ σατανᾶς κατοικεῖ.

I know where you dwell, where Satan’s throne is. Yet you hold fast my name, and you did not deny my faith even in the days of Antipas my faithful witness, who was killed among you, where Satan dwells. (ESV)The trickiest part here is grammatical—what should we do with the nominative after ἐν ταῖς ἡμέραις when we expect genitives? The commentators will tell you that scribes tried to smooth this by adding αἷς before Ἀντιπᾶς and that’s what we find in the Byzantine text. The syntax still isn’t great since we’re left with a verbless clause, but some have suggested that it is implied.

Others have followed Lachmann’s conjecture of Ἀντιπᾶ (the “proper” genitive of the name) suggesting that the sigma arose from dittography involving the article: αντιπα ο μαρτυϲ → αντιπαο ο μαρτυϲ → αντιπαϲ ο μαρτυϲ. That is one too many steps for my liking though.

Where things get more interesting is in the Syriac. Here is what we find in the British and Foreign Bible Society (BFBS) edition which is also the basis for the recent Gorgias edition. I’ve highlighted the main differences with the Greek:

ܝܳܕ݂ܰܥ ܐ̱ܢܳܐ ܐܱܝܟܴ݁ܐ ܥܳܡܰܪܬ݁ ܂ ܐܱܬ݂ܱܪ ܕ݁ܟ݂ܽܘܪܣܝܶܗ ܕ݁ܣܳܛܴܢܳܐ ܂ ܘܰܐܚܺܝܕ݂ ܐܱܢ̄ܬ݁ ܒ݁ܫܶܡܝ ܂ ܘܰܒ݂ܗܰܝܡܳܢܽܘܬ݂ܝ ܠܴܐ ܟ݁ܦ݂ܰܪܬ݁ ܂ ܘܰܒ݂ܝܱ̈ܘܡܳܬ݂ܴܐ ܐܷܬ݂ܚܪܻܝܬ݁ ܘܣܳܗܕܴ݁ܐ ܕܻ݁ܝܠܝ ܂ ܡܗܰܝܡܢܳܐ ܂ ܡܶܛܾܠ ܕ݁ܟ݂ܽܠ ܣܳܗܕܴ݁ܐ ܕܻ݁ܝܠܝ ܡܗܰܝܡܢܳܐ ܂ ܐܱܝܢܳܐ ܕ݁ܡܶܢܟ݂ܽܘܢ ܐܷܬ݂ܩܛܷܠ ܂

I know where you dwell, the place of Satan’s throne, and you hold fast my name, and you did not deny my faith even in the days when you contended, even my faithful witness, because every witness of mine is faithful, the one who was killed among you [omit].So we have (1) the verb “you contended” substituted for the name “Antipas,” (2) the long addition of the phrase “because every witness of mine is faithful,” and (3) the omission of the final clause “where Satan dwells”—none of which you will find in the NA/UBS editions. You have to go all the way to Hoskier (or at least a footnote in Beale) to find the addition.

The first variant has a good explanation in that Ἀντιπᾶς is sometimes spelled αντειπας and this could be read as an Aorist form of ἀντιλέγω. Hence we get ܚܪܐ in Syriac which means “resist, dispute, contend,” etc. in the ethpeal. Tischendorf tries to explain the Syriac as a translator’s failed attempt to render the name. But explaining it as a different way to read the Greek is much more viable especially because Hoskier lists several Greek minuscules that seem to accent it as the verb (ἀντεἶπας rather than ἀντειπᾶς).

The third variant, the omission of the last phrase, is a bit easier to explain in Syriac than in Greek. In Syriac, it looks like a case of homoioteleuton involving ܐܠܐ at the beginning of v. 14. The phrase is included in the Harklean Syriac manuscripts, so, apparently, it didn’t last long. It’s only attested by two minuscules in Greek perhaps just by accident.

The second variant, the addition, is the most surprising of the three. It is also not unique to the Syriac, being found in over a dozen Greek minuscules. This suggests that the Syriac is not innovating but rather reflecting its Greek Vorlage. In his edition, Gwynn argues the same but still calls the longer reading an “interpolation.” What he doesn’t mention but should have is that its omission has an obvious explanation by way of homoioteleution, the scribe’s eye jumping from πιστός to πιστός (cf. GA 2028).

|

| Rev 2.13 in GA 2028 (15th cent.) showing the longer reading. |

None of this made it into the sermon, you’ll be relieved to know. But I wonder if some of these readings shouldn’t make it into the Nestle apparatus. The longer reading in particular belongs there not only for its exegetical significance, but because, at least transcriptionally, it can explain the shorter reading.

Monday, November 02, 2015

A Three Part Correction to the Editio Critica Maior at 1 John 3.24

I use the Editio Critica Maior frequently and I continue to be impressed by how well it combines clarity with great detail. Yes, it takes a bit of getting used to its format (as with any large apparatus), but once you’ve got the basics, it’s great.

But occasionally, I do find that it has mistakes. 1 John 3.24 is a case in point. The ECM records the first hand of 180 and both Syriac versions as attesting a dittography of the first ἐν αὐτῷ in καὶ ὁ τηρῶν τὰς ἐντολὰς αὐτοῦ ἐν αὐτῷ μένει καὶ αὐτὸς ἐν αὐτῷ. But, in fact, a check of Aland’s edition of the Syriac shows that there is no such dittography. Both versions have the equivalent of each occurrence of ἐν αὐτῷ (ܒܗ) just once. I suspect this was a simple case of the Syriac sigla being put with the wrong variant address. But there’s more.

Since I was checking, I tried looking at the images for GA 180 in the VMR but quickly realized that what I was looking at was a manuscript of only the Gospels. This led me to Elliott’s Bibliography where I learned that part of GA 180 has a new number: GA 2918. As best I can tell, GA 2918 is in the same codex as 180 (Borg. gr. 18) but, since the Gospels are in a different hand of a different date, they now have a different GA number. Apparently the change happened after the ECM was printed, so it still reflects the old number.

Checking the images for 2918, then, I found a third problem. Ιt looks to me like the scribe of 2918 has not written the first ἐν αὐτῷ twice, but rather ἐν αὐτοῦ, his eye jumping to the wrong αυτ-. The ECM is right about the correction though; it’s just the original error that’s incorrect.

All this means that if you were only reading the ECM apparatus, you would be led astray in three ways: (1) you would have the wrong reading for 180*; (2) you wouldn’t know that GA 180 has been split numerically in two (and so wouldn’t find it in the VMR); and (3) you would wrongly think that the Syriac tradition agreed with it in error. Thankfully, with just a little digging, all three problems can be spotted. Maybe in another printing it can be fixed.

I suppose the lesson from this is that producing a good critical apparatus is complicated work with numerous points at which the process can break down. A second lesson follows from this: check your sources!

But occasionally, I do find that it has mistakes. 1 John 3.24 is a case in point. The ECM records the first hand of 180 and both Syriac versions as attesting a dittography of the first ἐν αὐτῷ in καὶ ὁ τηρῶν τὰς ἐντολὰς αὐτοῦ ἐν αὐτῷ μένει καὶ αὐτὸς ἐν αὐτῷ. But, in fact, a check of Aland’s edition of the Syriac shows that there is no such dittography. Both versions have the equivalent of each occurrence of ἐν αὐτῷ (ܒܗ) just once. I suspect this was a simple case of the Syriac sigla being put with the wrong variant address. But there’s more.

Since I was checking, I tried looking at the images for GA 180 in the VMR but quickly realized that what I was looking at was a manuscript of only the Gospels. This led me to Elliott’s Bibliography where I learned that part of GA 180 has a new number: GA 2918. As best I can tell, GA 2918 is in the same codex as 180 (Borg. gr. 18) but, since the Gospels are in a different hand of a different date, they now have a different GA number. Apparently the change happened after the ECM was printed, so it still reflects the old number.

Checking the images for 2918, then, I found a third problem. Ιt looks to me like the scribe of 2918 has not written the first ἐν αὐτῷ twice, but rather ἐν αὐτοῦ, his eye jumping to the wrong αυτ-. The ECM is right about the correction though; it’s just the original error that’s incorrect.

|

| 1 John 3.24a in GA 2918 (formerly GA 180) showing the deletion marks around εν αυτου |

All this means that if you were only reading the ECM apparatus, you would be led astray in three ways: (1) you would have the wrong reading for 180*; (2) you wouldn’t know that GA 180 has been split numerically in two (and so wouldn’t find it in the VMR); and (3) you would wrongly think that the Syriac tradition agreed with it in error. Thankfully, with just a little digging, all three problems can be spotted. Maybe in another printing it can be fixed.

I suppose the lesson from this is that producing a good critical apparatus is complicated work with numerous points at which the process can break down. A second lesson follows from this: check your sources!

Monday, July 27, 2015

Book Review: The Gospel of Mark in the Syriac Harklean Version (2015)

Samer Soreshow Yohanna. The Gospel of Mark in the Syriac Harklean Version: An Edition Based upon the Earliest Witnesses. Biblica et Orientalia 52. Rome: Gregorian & Biblical Press, 2015. xi + 196. €48 (hardback); £5.75 (e-book)

Samer Soreshow Yohanna. The Gospel of Mark in the Syriac Harklean Version: An Edition Based upon the Earliest Witnesses. Biblica et Orientalia 52. Rome: Gregorian & Biblical Press, 2015. xi + 196. €48 (hardback); £5.75 (e-book)“No other branch of the church has given so much effort to spread and to accurately transmit the Gospel. From the hills of Lebanon and Kurdistan, from the Mesopotamian plains and the coast of Malabar, even from faraway China, Syriac manuscripts that are valuable for textual criticism have come to the European libraries.” —Eberhard Nestle

1. Background

The Syriac speaking church has left us one of the richest traditions of Biblical translation. The translation of the New Testament starts with the Gospels as early as the second and third centuries with Tatian’s Diatessaron and the Old Syriac Gospels. The Peshitta came next and was to become the most prominent of all the Syriac translations. Even so, the heat of theological controversy led to a number of more exacting translations which were intended to help settle matters of exegetical dispute. The Philoxenian was completed in 508 and was the first to include the small Catholic Epistles and possibly Revelation, the former being all that survives to us today. The last of the major translations and the most literal was that of Thomas of Harkel who finished his work in 616, shortly after Paul of Tella’s completion of the Syro-hexepla. |

| Even with native Aramaic, Thomas gives the Greek (e.g., μαραναθα in 1 Cor 16.22) |

Saturday, June 27, 2015

Online Database of Syriac Manuscripts

There is a fairly new online database for Syriac manuscripts called e-ktobe. The aim of the database—listing “all syriac manuscripts in the world”—is quite ambitious. From the website:

On the topic of Syriac, the latest issue of Novum Testamentum has an article by Christophe Guignard on one of the newest majuscules to receive a Gregory-Aland number. In the under text of the Old Syriac palimpsest Codex Sinaiticus, there are four leaves of John’s Gospel from the 4th-5th century. This text has been known for 120 years but is only now receiving its proper GA number. Sadly Guignard doesn’t give us any pictures.

The article is “0323: A Forgotten 4th or 5th Century Greek Fragment of the Gospel of John in the Syrus Sinaiticus,” NovT 57.3 (2015), 311-319.

E-ktobe is a database on Syriac manuscripts which aims to collect information on texts, physical elements, colophons and notes. It will enable any researcher to make a request on texts, authors and codicological elements for all the Syriac manuscripts in the world. Thanks to this database, you can search for some material details, do multi-criterial research, and also make a request about one person connected with the making of Syriac manuscripts (copyist, restorer, sponsor, owner...). The main scientific goals of this project are to give insight into the cultural history of Syriac communities and develop Syriac codicology.Unfortunately the database seems a bit sparse at the moment. If there are 10,000 extant Syriac manuscripts according to one recent estimate (Binggeli, p. 502), then the current database lists about 5% of all Syriac manuscripts. At the moment, a search of the largest catalogue in Europe (the British Library) only turns up five results! Given this, the 136 results filtered for Old and New Testament should be taken as a drop in the bucket.

* * *

On the topic of Syriac, the latest issue of Novum Testamentum has an article by Christophe Guignard on one of the newest majuscules to receive a Gregory-Aland number. In the under text of the Old Syriac palimpsest Codex Sinaiticus, there are four leaves of John’s Gospel from the 4th-5th century. This text has been known for 120 years but is only now receiving its proper GA number. Sadly Guignard doesn’t give us any pictures.

The article is “0323: A Forgotten 4th or 5th Century Greek Fragment of the Gospel of John in the Syrus Sinaiticus,” NovT 57.3 (2015), 311-319.

Wednesday, October 22, 2014

Oxford Syriac Conference Jan 2015: Call for Papers

Syriac Intellectual Culture in Late Antiquity: Translation, Transmission, & Influence

This conference explores the intellectual cultures of Syriac-language literary and scholarly communities of the late antique (c. 3rd–9th century) Near and Middle East. It will also provide an opportunity for postgraduate and emerging scholars in the fields of biblical studies, theology and religion, late antique and Byzantine studies, near eastern studies, and rabbinics to present their work on Syriac literature within the University of Oxford’s vibrant late antique studies community.The conference welcomes proposals for papers on the following and related topics:

- The reception and revision of Syriac biblical translations, especially works such as the Harklean and Syrohexaplaric versions and Jacob of Edessa’s Old Testament revision. How did Syriac authors navigate the diversity of translation options available to them? How were later translations and revisions received in both exegetical and liturgical contexts? Which textual variants were employed by exegetes, and in what contexts?

- What role do translations of Greek patristic literature, such as the works of Gregory Nazianzen and Theodore of Mopsuestia, play in the context of Syriac literature? How is material from Greek historiography, such as the ecclesiastical histories of Eusebius, Socrates, and Theodoret, translated and transmitted by Syriac chroniclers?

- What factors played a part in the development of literary canons and exegetical traditions in Syriac? How did different communities determine which texts to elevate to canonical status? When and why were authors from rival communities read and utilized? How did Greek-language authors, such as Severus of Antioch, undergo a process of ‘Syriacization’? Which authors survived the decline of spoken Syriac and were translated into Christian Arabic, and how?

- What forms did Syriac intellectual life take over the course of the period, in monastic, scholarly, and church communities? How did Syriac culture react to and interact with influences such as Aristotelian and neo-Platonist thought, rabbinic scholarship, and other vernacular literatures? What role did Syriac scholars play in the early development of Arabic-language intellectual culture, and how did this role affect or change their own traditions?

Those wishing to present a twenty-minute paper may submit a brief abstract (250 words or less) and academic biography to oxfordsyriac2015@gmail.com. The deadline for submissions is Monday, 17 November 2014.

Thursday, March 18, 2010

Syriac New Testament Bibliography

|

| Peshitta Gospel lectionary (source). |

Aland, Barbara. “Die Übersetzungen ins Syrische, 2. Neues Testament.” TRE 6:189–96.

——. “Die philoxenianisch-harklensische Übersetzungstradition: Ergebnisse einer Untersuchung der neutestamentlichen Zitate in der syrischen Literatur.” Mus 94 (1981): 321–83.

Aland, B. and A. Juckel. Das Neue Testament in syrischer Überlieferung, I. Die grossen katholischen Briefe, II. Die Paulinischen Briefe, 1. Römer- und 1. Korintherbrief, 2. 2. Korintherbrief, Galaterbrief, Epheserbrief, Philipperbrief und Kolosserbrief, 3. 1./2. Thessalonicherbrief, 1./2. Timotheus¬brief, Titusbrief, Philemonbrief und Hebräerbrief. 4 vols. ANTF 7, 14, 23, 32. Berlin, New York: de Gruyter, 1986, 1991, 1995, 2002.

Friday, March 16, 2007

The Prologue of Revelation in the Syriac Text

In reading the latest issue of JETS the article by John Noe includes a reference (derived from James M. MacDonald) to the “Syriac version of the Bible” which apparently entitles Revelation as “The Revelation which was made by God to John the evangelist on the island of Patmos, into which he was thrown by Nero Caesar.” Is this peculiar to one particular ms or is it widespread? It would provide evidence that some in the Syriac church dated Revelation to the 60s.

The prologue to Revelation includes up to 60 different wordings (cited by H.C. Hoskier, Concerning the Text of the Apocalypse: Collations of All Existing GreekDocuments [1929], 25-27). I think the TR includes a reference to “John the Theologian” and 1775 includes the longest description: “The Revelation of the all-glorious Evangelist, bosom-friend [of Jesus], virgin, beloved to Christ, John the theologian, son of Salome and Zebedee, but adopted son of Mary the Mother of God, and Son of Thunder” -- that’s quite an introduction!

Interesting stuff!

Tuesday, February 20, 2007

Tremellius' Syriac New Testament

Thanks to Rob Price, who made me aware that a new article on Immanuel Tremellius has just come out in the Journal of Ecclesiastical History. Tremellius was a sixteenth century philologist who converted from Judaism to Catholicism to evangelicalism (associated with Cranmer and the Prayer Book) and who was for some time Professor of Hebrew in Cambridge. He was also the first person to distinguish between dialects of Aramaic, arguing that Syriac was not the dialect of Aramaic used by Jesus. The first edition of the Syriac NT was 1555. Tremellius’ 1569 edition, using Hebrew script, appeared visually inferior, but sought to use historical linguistics to restore the vocalisation of the Aramaic to its earliest form (and therefore a form closer to that of Jesus).

Details

Robert J. Wilkinson, ‘Immanuel Tremellius’ 1569 Edition of the Syriac New Testament’, JEH 58.1 (2007) 9-25.

Abstract

Tremellius’ 1569 edition of the Syriac New Testament was a quite distinctive product of Heidelberg oriental scholarship, very different from other sixteenth-century editions produced by Catholic scholars. Tremellius produced his edition by first reconstructing an historical grammar of Aramaic and then, in the light of this, vocalising the text of Vat. sir. 16 which he took to be more ancient than that of Widmanstetter’s editio princeps. Thus in this way he sought to construct the earliest recoverable linguistic and textual form of the Peshitta. The anonymous Specularius dialogus of 1581 is here used for the first time to corroborate this assessment of Tremellius’ achievement and to cast light on the confessional polemics his edition provoked.

Details

Robert J. Wilkinson, ‘Immanuel Tremellius’ 1569 Edition of the Syriac New Testament’, JEH 58.1 (2007) 9-25.

Abstract

Tremellius’ 1569 edition of the Syriac New Testament was a quite distinctive product of Heidelberg oriental scholarship, very different from other sixteenth-century editions produced by Catholic scholars. Tremellius produced his edition by first reconstructing an historical grammar of Aramaic and then, in the light of this, vocalising the text of Vat. sir. 16 which he took to be more ancient than that of Widmanstetter’s editio princeps. Thus in this way he sought to construct the earliest recoverable linguistic and textual form of the Peshitta. The anonymous Specularius dialogus of 1581 is here used for the first time to corroborate this assessment of Tremellius’ achievement and to cast light on the confessional polemics his edition provoked.

Friday, March 10, 2006

Foundations for Syriac Lexicography I

A. Dean Forbes and David G.K. Taylor, eds, have just brought out the volume Foundations for Syriac Lexicography I: Colloquia of the International Syriac Language Project (Piscataway: Gorgias Press, 2005). It contains much that is of interest to Syriasts and lexicographers with contibutors such as Terry Falla, Alison Salvesen, George Kiraz, Dean Forbes, Janet Dyk, Andreas Juckel and Sebastian Brock. Perhaps I may be forgiven for drawing attention to my own contribution, which is probably the one most relevant to textual criticism. It is: 'On Matching Syriac Words with Their Greek Vorlage' (pp. 157-166). Andreas Juckel, Syriac expert at the INTF in Münster, writes on 'Should the Harklean Version Be Included in a Future Lexicon of the Syriac New Testament' (pp. 167-194), which, despite the title, also includes material of text-critical interest.

A. Dean Forbes and David G.K. Taylor, eds, have just brought out the volume Foundations for Syriac Lexicography I: Colloquia of the International Syriac Language Project (Piscataway: Gorgias Press, 2005). It contains much that is of interest to Syriasts and lexicographers with contibutors such as Terry Falla, Alison Salvesen, George Kiraz, Dean Forbes, Janet Dyk, Andreas Juckel and Sebastian Brock. Perhaps I may be forgiven for drawing attention to my own contribution, which is probably the one most relevant to textual criticism. It is: 'On Matching Syriac Words with Their Greek Vorlage' (pp. 157-166). Andreas Juckel, Syriac expert at the INTF in Münster, writes on 'Should the Harklean Version Be Included in a Future Lexicon of the Syriac New Testament' (pp. 167-194), which, despite the title, also includes material of text-critical interest.

Subscribe to:

Posts

(

Atom

)

Loading...