Today’s guest post is from Mark Ward. Mark received his PhD from Bob Jones University in 2012; he now serves the Church as an Academic Editor at Lexham Press, the publishing imprint at Faithlife, makers of Logos Bible Software. He has written hundreds of articles for the Logos blog, and his most recent book is Authorized: The Use and Misuse of the King James Bible, a book “highly recommended” by D.A. Carson.

Today’s guest post is from Mark Ward. Mark received his PhD from Bob Jones University in 2012; he now serves the Church as an Academic Editor at Lexham Press, the publishing imprint at Faithlife, makers of Logos Bible Software. He has written hundreds of articles for the Logos blog, and his most recent book is Authorized: The Use and Misuse of the King James Bible, a book “highly recommended” by D.A. Carson.Though my efforts to grasp the CBGM have made me wonder if I should return all my biblical studies diplomas in shame, I am deeply grateful for the work of Evangelical Textual Criticism. I love to nerd out on all the asterisks and obelisks, and my stock method of impressing people at parties is to recite from memory all the NA28 sigla. (Not true.)

But I humbly suggest that believing textual critics ought to keep insisting to the church, for the good of the church, that most of their work is a tempest in a rather small teapot—and not the one Mother sets out when company comes over. Precisely because of my love for it, and after following it all these many years, and while acknowledging that textual criticism has chronological priority in exegesis, I insist that ETC is the etc. of biblical studies. It is the tithe on mint, dill, and cumin.

No, probably just the cumin.

And I have built a textual criticism teaching tool that, I hope, will help everyone see just how inconsequential the vast majority of textual decisions are: KJVParallelBible.org. After two years of labor, and helped along by numerous skilled volunteers, the site launches with the complete New Testament (plus study tools!) today.

What Is KJVParallelBible.org?

The site dedicates one page to each of the 260 chapters of the New Testament. On each of these pages are two columns. The left column is the KJV as it stands in the common 1769 Blayney edition. The right is the KJV as it would be if Peter Williams and Dirk Jongkind could travel back in time and hand the KJV translators an NA28—instead of the mixture of Stephanus (1550) and Beza (1598) the translators in fact employed. (In this imaginary scenario, I am asking them to hand over an NA28 rather than a THGNT—sorry.) The differences between the two KJVs are then highlighted.The result is a cheat sheet, in English, of all the translatable differences between the two most important printed GNTs in existence—their importance in this case being judged by one criterion: the TR and the NA are the only two texts major English translations have seen fit to translate.

|

| The homepage of KJVParallelBible.org |

Indeed, KJVParallelBible.org arose out of a personal calling I have to appeal to my brothers and sisters within KJV-Onlyism. My main work so far—a book and a documentary—has actually avoided textual criticism and focused on English, because I think NT textual criticism is too difficult a topic for most people to form a careful, firsthand opinion about.

Nonetheless, KJV-Only Christians who have responded to my work persuaded me that there had to be something I could do to make the work of textual criticism more accessible. And, in the process, I found that the site makes a great teaching tool for New Testament Introduction classes and even full-on textual criticism courses.

Now, I mean no offense and no discouragement to all my beloved ETC contributors when I compare their work to a seed small enough to get caught in one’s teeth. And I remember Jesus’ words: tithing on cumin is something which “ought not to be left undone.” Explaining to the church why there are textual footnotes in their Bibles is a necessary and perennial work. And on those days when someone such as Bart Ehrman upsets the TC teapot and the contents come spilling into very public view, I thank God especially for ETC.

But our argument against Ehrman is very commonly that he is making a mountain out of … a cumin seed. So how can we teach students about the complicated topic of NT textual criticism while keeping it in proper perspective? By giving students of the Bible the visual lessons implicit in KJVParallelBible.org.

Visual lessons from KJVParallelBible.org

And here are a few of the lessons—in fact, three (a number I arrived at through combining new CBGM techniques with Hebrew gematria via a formula only I know, and that there’s no way Peter Gurry would ever be able to understand).I’ll start with the most important lesson—and the most obvious.

1. What’s really remarkable about Scrivener’s TR and the modern critical Greek text is not how different they are, but how similar they are.

Standard critical editions of the Greek New Testament are awash in sigla, like pieces of cumin scattered all over each spread. Such editions also feature fat and complicated apparatuses on nearly every page. The visual emphasis (and this is heightened when one is informed that the apparatuses are not even exhaustive!) lies on the differences among NT manuscripts.But when I first designed and built KJVParallelBible.org and did some test chapters, something jumped out at me immediately. The overwhelming impression one gets upon viewing the TR and CT in parallel is the magnitude not of the differences but of the similarities.

|

| Philippians and James in parallel |

Verse after verse in the two texts is precisely the same. Sometimes whole chapters are. And even the variants that show up are frequently so minor that I feel grieved to the heart to know that Christians fight over these things, or (worse) lose their faith over them.

Textual criticism is one of those fields in which statistics can be both genuine facts and damned lies (and I use that word advisedly!) at the same time. The variants between manuscripts do amount to something huge, numerically, this is true—and that is understandably scary to anyone who believes that the Bible is the inspired word of God. But I must condemn it as a lie if it is used to insinuate that there are numerous meaningful, viable, doctrinal differences between the major printed Greek texts.

2. English makes certain patterns in the variants more visible.

“Insufficient sampling” is a common temptation in textual criticism. Both scholars and laypersons can form judgments based on very slim selections of the data. And, truth be known, given the state of original languages education, the number of people who can read Koine Greek with anything close to fluency and rapidity is vanishingly small. It’s so laborious to take in textual critical data, even when you “know” Greek, that it’s hard to go quickly enough to get a big sampling to chew on. Most people can’t “skim” Koine.But they can skim English. I myself felt I’d entered a new world as I worked through more and more chapters of the NT on KJVParallelBible.org. Suddenly I could take big bites of the data at once. Whereas (metaphor change alert) I had previously dug deep into individual textual-critical problems, now I could fly over bunches of variants at, say, drone level. Suddenly I noticed patterns that I don’t think I could have seen in any other way.

Three brief examples:

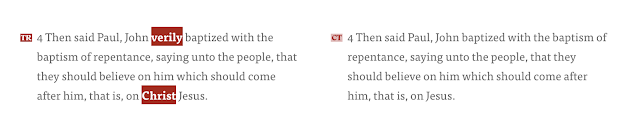

A. “Jesus Christ” and “Christ Jesus” are a common variant pair. I knew this on a theoretical level: I’d read it as a postulate in various discussions of textual criticism. But to see it over and over and over is to sense that there had to be some kind of rhyme and reason, some kind of program or purpose. My suggestion: use KJVParallelBible.org to find possible patterns in the variants, and then do your digging in the Greek.

|

| Philippians 1 |

|

| Acts 19 |

|

| Acts 19 |

B. I’ll put this on the hypothesis level—I’m not ready to conclude anything yet; but Revelation appears to me to be worse, textually, than other books. I uploaded Revelation last, and after looking at 238 other chapters in the NT, Revelation’s number of variants jumped out at me visually. (I still think the similarities jump out more than the differences, but the jump in the latter seemed noticeable.) Even if my hypothesis turns out to be wrong, I found it in the best way: through a sufficient inductive sampling of data. And now I can test it.

C. The TR is not so much “longer” as “easier” or “smoother” and therefore longer. A staple argument of KJV-Only apologists is that the critical text “omits” certain statements. This, of course, presumes that the TR didn’t “add” them. And I came away from looking at all the data more convinced that the critical text explanation makes the most sense: it seems far easier to me to explain the longer text in the TR as smoothings than it is to explain why scribes would purposefully or accidentally omit words that cause interpretive difficulties. It’s kind of like the apocryphal additions to Esther—it’s easy to see why moral questions raised by the story (why didn’t Mordecai bow to Haman, and why did Esther willingly spend a night with a pagan king?) would occasion these additions.

Here’s the TR being helpful, as it likes to do, by specifying the referent of a pronoun:

|

| Revelation 21 |

Here’s the TR filling out an elliptical expression for the benefit of readers (not unlike many contemporary translations):

|

| Matthew 5 |

Here’s the TR making sure to specify that it’s only “those who are saved” who will walk by the light of the Lamb. Only if you assume that omission equals denial (first presuming, of course, that the CT “omits” rather than the TR “adds”) can you call this a doctrinal difference:

|

| Revelation 21 |

|

| Matthew 5 |

3. The same thing can be said with different words.

It’s one thing to say, “The variants between the TR and CT amount to an entire page/chapter/what-have-you.” That’s alarming for any evangelical worth his Mark 9:49. It’s another thing to actually look at these variants in context. People quickly forget how many statements in the NT are not remotely doctrinal, and—and I say this as an unabashed inerrantist—they overestimate the contribution of individual words to the meaning of sentences. Yes, it feels wrong to say that a perfect book can be changed without its meaning being changed, but it’s really true.Look for yourself. Here are three verses with variant units that were chosen at random by my TI-616 CBGM calculator, which comes with a random NT chapter selector:

|

| Romans 2 |

|

| Matthew 16 |

|

| 2 Corinthians 9 |

Of course, I don’t want to be in the business of figuring out how many variants can be introduced before doctrine changes, but I’ll observe that the Holy Spirit has already entered that business. The reason I can’t bring myself to believe that there is a “doctrine of perfect preservation” is both that it misinterprets various Scripture passages and that every jot and tittle is every jot and tittle. Unless we not only have every last stroke of the pen but have perfect confidence in which strokes belong and which don’t (even if one prefers the TR, what does he do with its variants?), God has not given us a world in which the Bible has been perfectly preserved. That is the standard Jesus sets up in Matthew 5:18—if indeed his words are talking about preservation at all, and not efficacy. Naturally, I take the latter view. The Spirit gave us a remarkably but not perfectly pure NT textual stream. I choose to be thankful rather than to demand better.

What the KJV translators said about translation I think they (and we) can say about textual transmission:

No cause therefore why the word translated should be denied to be the word, or forbidden to be current, notwithstanding that some imperfections and blemishes may be noted in the setting forth of it. For whatever was perfect under the sun, where Apostles or apostolic men, that is, men endued with an extraordinary measure of God’s Spirit, and privileged with the privilege of infallibility, had not their hand? (xxviii)

Conclusion

Of course, there is plenty of expert discussion on textual criticism, some of which has been made very accessible (including, notably, on the ETC blog). But TC is a necessarily inductive discipline—you cannot form an accurate impression of the variants out there without exposure to a great many of them. We do have excellent textual commentaries—Metzger/Omanson, Comfort, even Brannan and Loken’s Lexham Textual Notes, which covers the entire Bible and includes no Hebrew or Greek. But these, too, “leave out” data I have come to see as extremely important, particularly (but not only) for laypersons: they do not show English readers how many words in Scripture are precisely the same across major GNTs. After two years of work on KJVParallelBible.org, I have come to believe that a firm grounding in the differences and the similarities, inductively gathered, is the best defense against the unhealthy skepticisms of both Ehrman on the left and Ruckman on the right.KJVParallelBible.org is a teaching tool, a quick-reference cheat sheet, and (I pray) a resource to bring light to the church. I end the project grateful to the Lord for his word and its preservation.

I have now made my personal tithe on cumin and can move on to dill.

This is wonderful! Mark, great job in helping TC be accessible. Even further, thank you for trying to give the only-ists a more nuanced view of translations.

ReplyDeleteExcellent! "blessed are the peacemakers".

ReplyDeleteBravo!

ReplyDeleteThank you for all the work you did in compiling and sorting.

This side-by-side comparison is so very easy to use, and makes instantly clear how little the CT differs from the TR (and therefore, presumably, even less than from the Majority or Byzantine Text).

Mark,

ReplyDeleteThe issue of being able to see at a glance, a large swath of scripture in comparison, seems to me, to be the greatest value. One TC website focuses on sections of chosen passages to give the appearance that the early manuscripts are corrupted in comparison to MT. Kudos, Mark.

Tim

Matthew 16:8 has obviously been affected by parallelism to Mark 8:17. Take your pick; either the TR brought in αὐτοῖς or NA brought in ἔχετε. But I speak in a figure, as neither the editors of the TR or the editors of NA made any such move themselves.

ReplyDeleteThe TR's alleged urge to help the reader out doesn't come through in Revelation Chapter Six, where I count only two Stephanus expansions (a formulaic και βλεπε after every occurrence of ερχου, and πασ before ελευθεροσπασin v.15), as compared to four in the critical text ('seven' and 'with' in v.1, 'as it were' in v. 6, and 'whole' in v. 12).

ReplyDeleteThis is a great resource! Thank you so much!

ReplyDeleteThere is a very similar resource in print that I have recommended to people for a few years. I do not recommend the author or any of his other books, but I have found Jack Moorman's "8,000 Differences Between the N.T. Greek Words of the King James Bible and the Modern Versions" to be a useful resource. If I remember correctly (my copy is currently packed away somewhere), each 'opening' has two columns on each page. One is the TR (I don't remember which; maybe the Trinitarian Bible Society?) paired with the AV, and the facing page has the NA27 and an AV-styled translation that reflects the differences, if the differences make a difference in translation. It gives the same English text in both places for non-translatable differences, but it still gives the Greek to show what the differences are. I seem to remember it even includes differences like εστι/εστιν.

It's available here: https://www.amazon.com/Differences-Between-Modern-Versions-English/dp/1568480547

That being said, having a resource like yours that is online is far more useful because of its accessibility. Thanks again!

I suppose if one is only concerned with the differences between variants selected for inclusion in the base-texts of English translations, this has a use, as a tool for assuaging some concerns of apologetics-students. But whaddaya do at passages such as Mt 13:33 and Mt 27:49 and Mark 1:41 and Hebrews 2:9, and Jude 5, and Jude vv. 22-23, where things get a little complicated?

ReplyDeleteApparently not much.

Btw, the links in the Table of Contents are a little glitchy; all the chaoters in Matthew after Matthew 21 seems to be linked to Matthew 21.

James, thanks for pointing out the issue on the TOC of Matthew. Those links should now be fixed.

DeleteNot snark...

ReplyDelete...but when your first sentence contains an acronym that I've never heard of, despite a post grad qualification that includes years of Greek, then I'm afraid your English became Greek to me! Perhaps only second and later instances of acronym-worthy phrases should get abbreviated? Please?

=) Good call. Maybe Peter can turn "CBGM" into a link to his book:

Deletehttps://www.amazon.com/dp/0884142671?tag=3755-20