Because we have been discussing the difficulty of counting manuscripts lately, I decided to jump in with my own way of making things worse minor contribution: It might be the case that Gregory 724 should be removed from the Liste.

|

| Gregory 724—the note in the front |

Details:

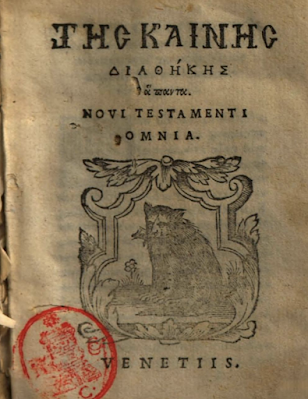

Gregory 724 is a Greek manuscript of the Gospels on paper+parchment and dated 1520. A note in the front of the manuscript even claims that it was copied from an edition of the New Testament ("scriptus fuit ex aeditione noui testamenti"). We know the copyist from this note, Levinus Ammonius, a Carthusian monk. There's an entry for him on pp. 50–51 of Bietenholz, ed., Contemporaries of Erasmus: A Biographical Register of the Renaissance and Reformation, vol. 1. A–E. According to Bietenholz, Ammonius lived from 13 April 1488–19 March 1557, and "...joined the Carthusian order, making his profession on 18 August 1506 in the monastery of St Maartensbos near Geraardsbergen, 30 kilometers west of Brussels."

Ammonius also had a bit of correspondence with Erasmus, and some of those letters have been published. Their first interaction (to my knowledge) occurred when Ammonius wrote to Erasmus on 4 July 1525 (Ep 1463, available in CWE 10), which the editor describes as "his first attempt to open a continuing correspondence with Erasmus." The editor continues: "His second attempt was successful (Epp 2016, 2062), and five of the letters in their subsequent correspondence survive (Epp 2082, 2197, 2258, 2483, 2817). The beginning of Ep 1463 shows the respect he had for Erasmus (my second-favorite Dutch scholar to live in Cambridge and edit a Greek New Testament): "For a long time I was full of misgivings, Erasmus most incorruptible of theologians, whether my action would be inexcusable if I were to interrupt you with a letter, I being a monk living obscurely in solitude and you the most distinguished of our whole generation for your outstanding gifts, and if I who enjoy the blessings of leisure were to inflict this tedium on a man who labours for the common good of Christendom."

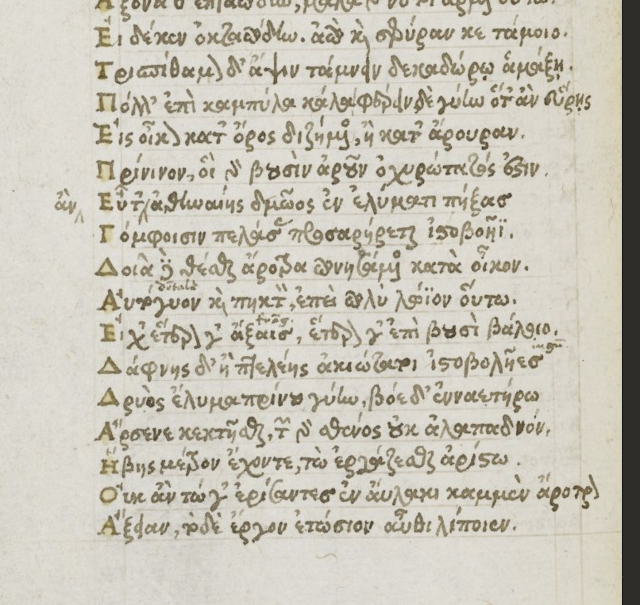

In Ep 2016 (available in CWE 14), Ammonius mentions that he had once copied out a Greek Psalter that Erasmus had even seen. Gamillscheg and Harlfinger (1981; Repertorium I a no. 10; p. 28) identify him as the copyist of Cambridge, Corpus Christi College ms 448, though the data at the Parker Library on the Web suggests that the copyist may have been Johannes Olivarius. This alternative identification seems to go back at least to K.A. de Meyier in 1964. That is all to say that by his own testimony, we can conclude that he copied at least one other Greek manuscript (and a Biblical text at that), and there may be at least one other manuscript copied by him that is now in the Parker Library at Corpus Christi, Cambridge. Here are samples of each below. I am not familiar enough with handwriting in this era to say anything about them worth taking too seriously, but I do see a lot of similarities. One thing that jumps out to me is that in the color images of CCC ms 248, the capital letters seem to have yellow 'around' them (or something that has faded to yellow), and I see the exact same pattern of 'discoloration' (for lack of a better word) in the microfilm of Greg. 724.

|

| Writing sample from Greg. 724 |

|

| Writing sample from Cambridge, CCC ms 248. |

Checks:

Pinakes mentions a few references for Greg. 724 that I haven't been able to check.

The first and second editions of the Liste are identical, save that it's on p. 100 in the 1st ed. and on p. 90 in the 2nd ed. (and the line break is at a different place in the location section). Here it is in the 2nd ed.:

724 is ε530 in von Soden's edition; here is his entry on vol. 1, p. 208:

"GA 724 has a Latin colophon that suggests it may have been copied from a printed edition in 1520: [[Libellus hic quatuor Euangeliorum scriptus fuit ex aeditione noui testamenti pr[ ... ] & postea ad tertiam eiusdem etc.]] In fact, except for not reproducing the spelling error 8:6 κατηγωρειν, the text agrees exactly with that of Erasmus 1516 (even Ιησους is written plene throughout; although my collation fails to note such for 8:1, this is almost certainly the case). The top margins appear like a printed book as well: ¶ ευαγγελιον || κατα ιωαννην. At 8:1 the margin has ¢ 8 sic. At 7:52 a corrector changed one form of abbreviation for και into another, without otherwise affecting the text."

How I found it:

I was reading an article about Erasmus and chased a rabbit trail. There's more to the story, but in short, the only manuscript I could find (at first) with the lives of the four evangelists by Dorotheus of Tyre (which Erasmus included in his 1516 edition, and only the 1516 edition) is 724. So obviously I looked into 724. I did end up finding the content elsewhere, so I can be confident that it's not another patristic forgery by Erasmus.

Conclusions:

1. Getting curious and chasing rabbits can lead to interesting things.

2. Robinson's collation data needs to be published! Where else do we get to see the work of someone who examined ~3,000 manuscripts and made notes about them.

3. Jacob Peterson might not have been wrong to extrapolate a level of error in counting manuscripts back into the minuscules and lectionaries. I wasn't looking for mistakes and, unless I am making one myself (which is certainly possible), I seemed to have happened upon one.

4. Even if 724 should be removed from the Liste, it could still be very interesting. Are there changes from Erasmus' 1516 edition? Do any changes represent textual decisions (or, dare we say it, conjectures?) of Levinus Ammonius? It may be just a boring copy of Erasmus 1516 with the usual sorts of scribal errors, but if we don't look, we won't know.