This forum is primarily concerned with textual criticism of biblical literature—and rightly so. Yet, the basic skills acquired in the course of studying biblical manuscripts can also come in handy when studying other textual traditions, including the ever-popular apocryphal Gospels.

This summer, I published a little

study of the so-called

Egerton Gospel (

GEg), an intriguing late second-/early third-century papyrus containing non-canonical Gospel-like material. (Many of our readers will have been familiar with this text, and I'd refer those who aren't to a brief but very lucid discussion in Markus Bockmuehl,

Ancient Apocryphal Gospels [Louiseville 2017] 106–10.) The topic of this article was borne a while ago as I read Francis Watson's

Gospel Writing, in preparation for Peter Head's reading group (which, I'm afraid, I never ended up attending, but that's another story).

In his chapter on the composition of John, Watson argues that the fourth evangelist re-interprets some of the material found in the

GEg, hence the latter preserves a tradition anterior to the Johannine account. Although Watson's overall argument is rather extended and intricate, the point of departure for his entire discussion is, in fact, a single reading of the Cologne fragment of the

GEg (the main portion of the text is housed in the British Library). In particular, Watson contends that, at ↓ 23,

GEg should read 'our fathers'. Thus, the entire

GEg parallel goes like this: εἰ γὰρ ἐπι[ϲτεύϲατε Μω(ϋϲεῖ)]· ἐπιϲτευϲάτε ἄ[ν ἐμοί· πε]ρ̣[ὶ] ἐμοῦ̣ γὰρ ἐκεῖνο[ϲ ἔγραψε]ν̣ τοῖϲ πατ[ρά]ϲ̣ι̣ν ἡμῶ[ν] ('If you had believed Moses you would have believed me, for he wrote them about me—to your fathers'). Most of this resembles John 5.46 quite closely, apart from the 'our fathers' bit, which Watson sets in contrast with John 6.49 where Jesus says: '

Your fathers ate the manna in the wilderness, and they died'. This being the case,

GEg preserves what Watson calls a 'Mosaic' stratum of the tradition, while John's material is a reinterpretation in view of the severance of his community from the synagogue.

At any rate, it would seem that Watson's argument is based on a misunderstanding of editorial conventions as well as of the reading itself. To begin with, he criticises Gronewald for reading ὑ̣μῶ[ν] in his articulated transcription whereas in the diplomatic transcription he prints ⟦η⟧`ϋ̣΄μω[ν. This, however, is a

standard papyrological practice of editing previously unknown literary texts: a diplomatic transcript is followed by a full/articulated transcription (as well as a translation based on the latter) where abbreviations are resolved and scribal corrections of initial errors are incorporated into the main text. Moreover, Watson doesn't seem to appreciate that his preferred reading is quite likely to have been an

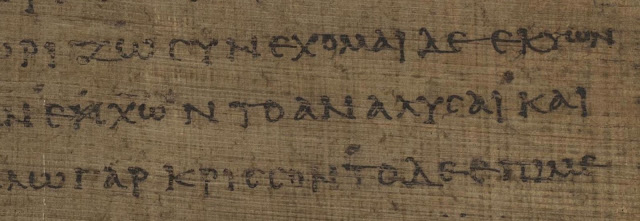

error corrected by the scribe himself (there are three further examples of such scribal behaviour in the papyrus). Although the surface is a bit damaged at this point, one can make out the remains of the eta having been partly written over by a supralinear upsilon (notice the trema over it, right below the iota on the previous line):

|

P.Köln VI 255↓ 22–3.

|

You can easily follow Gronewald's reasoning on the basis of this reconstruction. Obviously, there's always a possibility that both readings are 'good' (i.e. non-erroneous) but reflect divergent traditions—though this would be more plausible in a text with a wider circulation. Who knows how wide, if any, distribution

GEg may have enjoyed. In his aforementioned book, Bockmuehl observes that there's little reason to think that

GEg was widely read in early Christian communities. I tend to agree.