A long-ish post, but only because I care about data and getting it right.

One of the criticisms of Textus Receptus (henceforth, TR) advocacy is the question, “Which Textus Receptus?” (See the article by Mark Ward here). Instead of dealing with that question seriously, some TR defenders seem to brush it off as irrelevant.

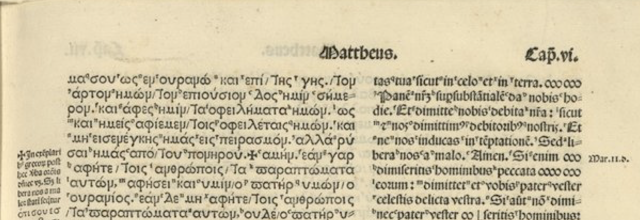

For example, one TR advocate recently claimed that even though there are ‘minor’ differences between editions of the TR, all of them have the Pericope Adulterae (John 7:53–8:11), all of them have the Longer Ending of Mark (Mark 16:9–20), all of them have the doxology on the Lord’s Prayer (Matthew 6:13), all of them have the Comma Johanneum (1 John 5:7–8), and all of them have the Ethiopian’s confession at Acts 8:37.

Unfortunately, that statement is simply not true. Familiarity with the editions of the Textus Receptus themselves demonstrates as much.

I have seen I think at least one TR advocate respond with the No True Scotsman argument, redefining “Textus Receptus” to include only the editions that do have these passages (thus excluding Erasmus’ first two editions). That objection doesn’t work for three reasons:

1. Martin Luther himself used Erasmus’ second edition for his German translation of the New Testament, which lacked the Comma Johanneum. Even though later Lutherans added it after his death, Luther himself still rejected it. Additionally, the 1537 Matthew’s Bible places it in brackets in smaller type, which does indicate textual uncertainty.

|

| Source: my own copy of the 1537 Matthew's Bible facsimile. |

2. By my count there are not two but (at least) six editions of the TR that lack the Comma Johanneum (and if you argue that ‘canon’ extends to the very form of the text, an argument could be made for more editions that have a form of the Comma Johanneum but with a number of variations from the form of the Comma Johanneum in Scrivener’s TR as republished by the Trinitarian Bible Society, which seems to be the standard TR now).

3. The Trinitarian Bible Society provides a definition of “Textus Receptus,” and their definition explicitly includes three of the six editions that lack the Comma Johanneum. In their article “The Received Text: A Brief Look at the Textus Receptus” originally published in the March 1999 edition of the Trinitarian Bible Society Quarterly Record (but presently linked on their website on this page), G.W. and D.E. Anderson write,

Today the term Textus Receptus is used generically to apply to all editions of the Greek New Testament which follow the early printed editions of Desiderius Erasmus. Erasmus of Rotterdam (1469?-1536), a Roman Catholic humanist, translated the New Testament into Latin and prepared an edition of the Greek to be printed beside his Latin version to demonstrate the text from which his Latin came. Erasmus used six or seven Greek manuscripts (the oldest being from the 10th century), combining and comparing them in a process in which he chose the correct readings where there were variants. On several occasions he followed the Latin and included some of its readings in his text. This edition was published in 1516. There was great interest in this Greek text, and it is the Greek text for which the volume is remembered. This New Testament was the first published edition of a Textus Receptus family New Testament.

They continue,

Numerous men during the past four centuries have produced editions of the Textus Receptus; these editions bear their names and the years in which they were published. These include:

- the work of Stunica as published in the Complutensian Polyglot (printed in 1514 but not circulated until 1522);the Erasmus editions of 1516, 1519, 1522, 1527 and 1535;

- the Colinæus edition of 1534 which was made from the editions of Erasmus and the Complutensian Polyglot.

- the Stephens editions (produced by Robert Estienne, who is also called Stephanus or Stephens) of 1546, 1549, 1550 and 1551;

- the nine editions of Theodore Beza, an associate of John Calvin, produced between 1565 and 1604, with a tenth published posthumously in 1611;

- the Elzevir editions of 1624, 1633 (the edition known for coining the phrase “Textus Receptus”) and 1641.

Of note here is that the Trinitarian Bible Society, one of the leading institutions defending the TR as well as the the publisher of what is almost certainly the most widely-used edition of the TR, explicitly names the Complutensian Polyglot, all five of Erasmus’ editions, and the 1534 Colinaeus edition as editions of the TR. If we want to make claims about "all editions of the TR," the Trinitarian Bible Society’s definition of what counts as a TR is probably the best definition to use. Here we should remember that Scripture doesn’t tell us which editions count as true TRs or even which manuscript(s) to use.

In what follows, I want to show that it is simply not correct to claim that “the editions of the TR all contain” those five passages. By my count (and I admit I have not looked exhaustively), there are at least six editions of the TR that lack the Comma Johanneum and one that lacks the doxology of the Lord’s Prayer and Acts 8:37. Then I will follow up with some thoughts.

Editions of the TR that lack the Comma Johanneum

As I mentioned, by my count there are at least six editions of the TR that lack the Comma Johanneum. In his book Biblical Criticism in Early Modern Europe, Grantley McDonald lists another two—in addition to the six I list, he also claims that Bebelius’ 1524 and 1531 editions lack the Comma Johanneum. I have not been able to find images of the 1531, but I did find images of the 1524 and can confirm that it does have the Comma Johanneum, contrary to McDonald’s claims. On that basis, I will also omit the 1531 on the grounds that I haven’t been able to verify its text. I have marked with a red arrow the point after the “there are three witnesses” where we would expect to see “in heaven ...” if the Comma Johanneum were present.

1. Erasmus’ first edition (1516)

|

| Source: https://www.e-rara.ch/bau_1/doi/10.3931/e-rara-2849 |

2. The Aldine Edition (1518)

|

| Source: https://www.e-rara.ch/bau_1/doi/10.3931/e-rara-72721 |

3. Erasmus’ second edition (1519)

This one occurs over a page break for the full text, so here are images of both parts.

4. Gerbellius’ edition (1521)

|

| Source: https://sammlungen.ulb.uni-muenster.de/hd/content/titleinfo/5374967 |

5. Wolfgang Köpfel’s edition (1524)

CSNTM owns a copy of this edition. |

| Source: http://diglib.hab.de/drucke/alv-u-272/start.htm |

6. Colinaeus’ edition (1534)

|

| Source: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/102392967 |

Other instances where an edition of the TR does not agree with others in all five places

|

| Source: p. 2398 at http://bdh-rd.bne.es/viewer.vm?id=0000013439&page=1 |

So what?

At the end of the day, one could argue that there was eventually a consensus and that these examples don’t actually matter. That might be especially the case for the two additional examples from the Complutensian Polyglot—I haven’t checked to see if other TRs make those same omissions. That argument would be fine, except that isn’t the claim that often gets made. The claim that gets made is that TRs all agree in these ‘major’ passages, and they only disagree in ‘minor’ places.That claim is demonstrably untrue—there’s just no way around it.

I expect one could find even more places of difference, especially where the Complutensian Polyglot goes off on its own, and especially in Revelation. But to say with certainty would take more familiarity with the data than I currently have other than in a couple of instances (compare the Complutensian Polyglot to Erasmus’ first two editions at Rev. 1:2 and 1:11, for example). If we focus only on a handful of ‘test passages’, we can easily miss differences that occur where we aren’t looking—especially if we are not even accurately representing what is happening where we are looking. Worse still is taking the ‘absence’ (or rather, unawareness) of evidence where we aren’t looking as evidence of absence in general or assuming that there is no such evidence simply because we are unaware of it.

I am on record for opposing misinformation when it comes to New Testament textual criticism, and I have even had to confess my own sins in this area (see p. 108 in the book referenced in the most recent link). If somebody wants to use a particular edition because textual criticism is hard and they have a hard time evaluating modern text-critical claims but they trust they will be safe if they use an edition that God has used for a few hundred years, I have absolutely no problem with that. However, I do have a problem with misinformation—wherever it comes from (myself and my friends included). God’s Word is too important to make arguments for or against it out of careless (incorrect) assertions about things that can be easily verified. (Perhaps you will have noticed that for some of these longer posts, I try to load them down with links to the actual sources or bibliographic entries so that you can check my claims instead of just taking my word for them.)

Jesus said, “He that is faithful in that which is least is faithful also in much: and he that is unjust in the least is unjust also in much” (Luke 16:10, KJV). The little details matter to Jesus, and they should matter to us as well. All the more reason to work “as to the Lord, and not unto men” (Col. 3:23 KJV) when it comes to having familiarity with the data that we write and speak about, and it’s never been easier than now with so many manuscripts and editions available online, freely accessible by anyone! A great place to start is here.

UPDATE (2 Dec. 2021): I did manage to find images of the 1531 Bebelius edition here, and I can confirm that it does have the Comma Johanneum (page view “[671] - 339r”).

- I’ve seen many claim that TRs differ only in minor matters, so the intent of the post was to give images of divergent editions for anybody who has heard those claims from whatever source. Dr. Riddle’s comments in the interview are just what reminded me that this claim circulates, which is why I linked to the video.

- I don’t think I misrepresented Dr. Riddle when taken in context with how he represented himself in the interview. I assumed it was just a simple mistake. I don’t think it is fair to assume that when he says “all editions,” the average listener will know that he really means “only some editions.”

- The TBS did refer to those editions as editions of the Textus Receptus in their doctrinal statement and/or (explicitly so) in literature posted to their website (by the Andersons).

- Regarding my statement that precipitated the ‘lazy, dim-witted, and emotionally insecure’ comments, I meant nothing negative. Dr. Riddle himself posted the same sentiment approvingly (“... it is the safest course to let the scale of the received text and traditional belief preponderate...”) earlier this year.

Hi, Elijah😊

ReplyDeleteThank you, - wonderful reading👍

I were a ‘TR’ guy in my youth, until I started to study the origin of the manuscripts. There is no doubt among evangelical scollars today, that the passages mentioned are at the best uncertain.

TR and KJV onlyists, are not willing to examim the data, they hold a religious belief in this aspext, - its just lik arguing with ‘Jesus only’ folk’s, - they’ve got all the materials, but draw the wrong conclution.

BUT again, thank you, I think your piece will open som eyes😊

Vidar Fossum, Norway

Thank you for pursuing this issue. My interest in textual criticism comes, at least partially, from my KJV-only background. The argument that eventually convinced me was that the KJV has a few reading supported by zero Greek manuscripts.

ReplyDeleteMy inability to read antiquated language of the King James substantially hindered my ability to read the Bible and coming out of KJV/TR onlyism was one of the most painful experiences of my life. There are days I still feel like a heretic even 8 years later.

I have a strong desire to help others with the same issues I struggled with, but have difficulty knowing how to address these issues with laypeople without undermining their confidence in Scripture. "Which TR?" is a crucial question that I hope can be used to help people see the distinction between inspiration and transmission. One day, if the Lord allows, I hope to do Ph.D. work in textual criticism and make it of service to the church as you are doing. Please continue to pursue these issues. May the Lord bless you as you serve and follow Him.

I love this comment. My background is similar.

DeleteTo address your struggle about not undermining laypersons' confidence in Scripture, remember to do two things. First, don't pile academic arguments on them. Start with one or to clear examples (the CJ is a great place to start). You can add details as interest grows.

Second, be sure to talk about the *means* God used to preserve his word, and how having multiple historical documents with variants is *better* than having one document with no historical background. Emphasize the importance of means in a world where we walk by faith and not by sight, and how the means God chose are the best option in multiple ways.

May the Lord bless you as well!

...one or *two* clear examples... :-(

DeletePossibly one verse you could focus on is Revelation 16:5. It is not as emotionally charged as 1 John 5:7-8, but is just as clear about what happened. Therefore, it can be used without as much prejudice to fight, and it can be used without too badly confusing people who have just learned that there are different editions of the TR. In Rev. 16:5, most Greek manuscripts read ὁ ὢν καὶ ὁ ἦν, ὁ ὅσιος, which can be translated as "The One who is and who was, the holy One." And editions of the Textus Receptus by Erasmus and Stephanus read something like ὁ ὢν καὶ ὁ ἦν καὶ ὁ ὅσιος, and they were translated in ways such as "Which art, and Which wast: and Holy." But then Theodore Beza changed it to ὁ ὢν καὶ ὁ ἦν καὶ ὁ *ἐσόμενος*--with no Greek manuscript evidence listed for it.

DeleteUnfortunately, a few years after that change to the New Testament, the KJV was translated and the translators followed Beza's change in this verse. Thus, the KJV has no Greek basis for "and shalt be".

Centuries later, Scrivener created another edition of the Textus Receptus that also reads "ἐσόμενος"--but it was only because the KJV followed that alteration, not because he thought it was in the autograph.

I think most people who use the KJV want to have the confidence that their Bible has the right words in it. That they have the same Bible (in a translation) that the Apostles wrote.

In this case, the truth hurts a little, because there was a bad change made to the Textus Receptus in the clearly traceable past. It will not really solve the problem to say that, no matter which way the verse reads, it is still true. Because it is not only truth that KJV readers want; they also want to have the confidence that the words of their Bible are preserved and inerrant.

Perhaps, in this case, they will need to pencil in a note at Revelation 16:5 at "and shalt be", saying, all Greek manuscripts read "the Holy One".

I think you speak for many people, Unknown. So I hope such textual differences can be discussed in a way that is constructive in the long run.

Folks might also want to investigate the TR's non-original /omissions/ in Colossians 1:6, Jude v. 25, etc.

DeleteThank you, Elijah.

ReplyDeleteYou write: "Additionally, the 1537 Matthew's Bible places it in brackets in smaller type, which does indicate textual uncertainty."

FWIW, There are several other important early English translations which do the same (or similar) thing, e.g. Tyndale, Coverdale, Cranmer (Great Bible), Taverner’s Bible. (If memory serves.)

MMR, Thanks for this. I figured there are more, but (with the exception of Luther) I wanted to stick to things for which I had easy access to images. It's harder to dismiss contradictory evidence when there's a picture to prove it, and I've seen the inverse of it happen. I seem to recall an instance on this blog of a dissertation-turned-monograph that on the surface seemed to vindicate some TR claims. I pointed out that in the unpublished version, the author had explicitly stated something to the contrary. I recall being met with something like "well we'll just have to wait for the published version then."

DeleteHear! Hear! I'd like defenders of "the TR" to be compelled by honesty and clarity to qualify "the TR" every time they are tempted to utter those syllables. There is no "the TR." There are multiple Texti Recepti. That simple recognition vastly complicates a lot of the talking points used by TR defenders. To have to say, "Scrivener's TR" or "Stephanus' TR" or "Beta's TR" (and I've heard TR defenders name each of these as the perfect one) would be helpful in this debate.

ReplyDeleteAbout a year and a half ago, Peter Gurry had a discussion with some TR defenders at Phoenix Seminary. I took down a bunch of words they used to describe "the TR," and I quote: “Pure,” “Perfect,” “Certain,” “Absolute,” “Stable,” “Settled,” “Not changing,” “Completed,” “Agreed upon.” They said, “There’s not a single place where [we] don’t know what the text says.” They said (didn't catch the exact words) that if there is uncertainty anywhere, there is uncertainty everywhere.

Dr. Gurry asked the question I pushed with my paper, the one you linked to, Elijah: how is it right for TR defenders to use the descriptors above when there is undeniable variation among TRs? There are dozens of differences between just the two TRs I’ve looked at in detail: Stephanus and Scrivener.

There aren’t just spelling and word order differences, though there are those. There are differences in number (sg. vs. pl.); there are differences in person (“us” vs. “you” in Mark 9:40); there are differences in tense and mood (Matt 13:24; Rev 3:12). There are wholly different words (Matt 2:11; 1 Pet 1:8; 1 Tim 1:4; 1 John 1:5; 2 Cor 11:10; 2 Thess 2:4; Phm 1:7; Heb 9:1; Jas 5:12; Rev 7:10).

And, significantly, there is an entire sentence—one which to me feels doctrinally important—present in Scrivener that is missing from Stephanus: 1 John 2:23. (Interestingly, that clause is all italicized in the KJV, which is the equivalent of the very textual-doubtfulness brackets that KJV proponents complain about in the ESV, NIV, etc.)

There are also two overt contradictions between Stephanus’ TR and Scrivener’s TR; see James 2:18 and Rev 11:2.

All TR advocates in my experience wish to continue to wave the “perfect” and “absolute” and “stable” and “settled” and “completed” flags. I don’t actually relish taking those flags out of their hands: I want people to have a sure and settled faith. But it’s when they wave those flags before laypeople and therefore cause division that I must gently pipe up from the back of the room. In my experience, precisely 0% of laypeople (and maybe 5% of pastors) in TR-using churches are aware that there are multiple TRs with differences among them; nor are they aware that the main TR used by their churches is a record of the textual-critical decisions of the KJV translators that never existed in the history of the world until Scrivener put it together in 1881. But I think the percentage of pastors, at least, is inching up—thanks to articles like this one, Elijah. I hope your work here takes some heat out of this debate by showing that it is indeed more complex than TR defenders tend to acknowledge. To their credit, some are starting to make this acknowledgement: I see them at least raising the "Which TR?" question, even if their answers are currently both sketched/incomplete and diverging.

The fact that the Greek text behind the KJV never existed in toto in print until 270 years after the KJV really does make one wonder about to appeals to the text “kept pure in all ages.” Not to mention the fact that Scrivener had to reconstruct it.

DeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

DeletePrecisely. TR defenders have frequently said in my hearing that the critical text never existed in the history of the world till 1881, but that is precisely the case with the TR edition they have been using and promoting—and frequently calling "perfect."

Delete*Correction: I meant "Beza's" TR! But it was kind of a beta version! ;)

I found Dr Riddle to be very Gracious in the interview and I was genuinely looking for some answers on the Confessional Text position. Something I've only heard of a few months ago. I was considering his answers to my questions about the his position and found the "Which TR" question to be a hurdle I couldn't get over. It seems by defining the TR as a tradition rather than an edition, it undercuts his position on providential preservation, because at the TR family level, there are still variants that need to be sorted out, just like the CT... Granted there are fewer, but this appears to be special pleading.

ReplyDeleteI think that if a confessional text advocate conceives of the text as (quoting from Mark's post above):

Delete"Pure, Perfect, Certain, Absolute, Stable, Settled, Not changing, Completed, Agreed upon. ... if there is uncertainty anywhere, there is uncertainty everywhere,"

then they cannot possibly remain coherent. And I think most confessional text proponents would fall into this.

But not all. For example, Theodore Letis expressly disavowed the doctrine of inerrant autographs, and I don't think he would have used any of that kind of rhetoric. I think he would have been as comfortable with the relatively small degree of variation that exists within the TR tradition as modern eclectic text proponents are with uncertainty about the autographs. The difference was that his ideal text was one faithfully represented the ecclesiastical text (his term for what, as far as I can tell, is the same thing as the confessional text), with little concern for how closely this text resembled the autographs. As far as Letis was concerned, if the ecclesiastical text contained "orthodox corruptions of scripture" (he was a huge Ehrman fan), that was a point in favor of both 1) the ecclesiastical text as a product of the Church that was guided to orthodoxy by the Holy Spirit over centuries and 2) those orthodox corruptions as preferred readings within the Church's Bible.

I think that some other champions of TR-only folks at the more academic end of the spectrum, such as Burgon and E. F. Hills, may also have been more judicious about their use of the kind of absolute demand for perfection that Mark alluded to than most TR proponents (of whatever specific variety) are.

Incidentally, despite his obvious theological differences with most of those that we encounter in the various TR-only type camps, Letis had a very favorable reputation among them, and by my observation still does with those who are familiar with his writings. Pensacola Christian College was enamored with him and put out a series of TR-only DVDs in the 90's that featured him as the main speaker, which they mailed out by the thousands to fundamentalist churches nationwide.

DeleteSurely Burgon can’t be considered TR-only can he? He roundly rejects 1 Jn 5:7 in the course of his defense of Mark 16:9–20.

DeleteAs do several of the TR editions, as Elijah points out.

DeleteIt might be anachronistic to call him TR-only, since I doubt that anybody would have framed their position as that until much later. But notice that all I said about him was that he is a champion of TR-only folks. I.e. whether he would have welcomed this role or not, TR-only folks today see him as that. I think that much is pretty safe to say.

DeleteEric Rowe,

DeleteIt would be more than anachronistic, it would be incorrect. Now, it is correct that many TR and KJV defenders champion Burgon (to some degree), albiet they are not in agreement with his position and methodology. (Nor resultant Greek text.)

Burgon's mind was made up to follow the most evidence — wherever that may lead, and regardless of whether such and such reading existed within any TR edition. His connection to the TR is basically twofold: 1.) Like Scrivener (and many others) he believed that the TR should be revised, and therefore used as the base text¹ for revision. 2.) That the TR should only be changed in cases where the preponderance of the evidence is notably sufficient. In cases where the evidence against any TR reading is not what he deemed sufficient, it should be left alone. Again, this type of mindset can be found (to some degree) in Scrivener, Wordsworth, Alford and even Griesbach.

If Burgon were alive today, he would likely fall somewhere in-between the views of Robinson and Snapp. Sideing sometimes here, and sometimes there.

¹ I suppose Stephanus 1550 or Mill would have been his final choice here. Although any TR edition would do.

Perhaps another point regarding Burgon and the TR should be noted in this context: He, like Scrivener before him, believed that the TR was closer to the originals than the respective critical text editions of his day.

Delete*Siding

DeletePeter,

DeleteCorrect. I'll try to revisit this point when I get a chance to dig up a quote from Burgon about him longing for the day with a proper revision of the TR would become feasible.

James Snapp Jr.

Seems like if that hasn't happened by now, it's ain't going to. Getting people together who aren't TR-only and don't like the eclectic texts already on offer sounds like wrangling cats.

DeleteBurgon knew nothing of the KJO or TRO movements, but he prophesided of them in his first TC book, The Last Twelve Verses of Mark: "The co-ordinate primacy, (as I must needs call it,) which, within the last few years, has been claimed for Codex B and Codex א, threatens to grow into a species of tyranny,----from which I venture to predict there will come in the end an unreasonable and unsalutary recoil.”

DeleteWhy is the Complutensian Polyglot considered a TR text? It was my understanding that Erasmus' work was developed completely independently of the CP.

ReplyDeleteHi Dwayne,

DeleteGood question.

Erasmus used the Complutensian as a source in his 3rd edition on. And it was used by Stephanus as well, thus it would effect Beza. The CP has a solid place in the TR tradition.

You can consider the general excellence and closeness of the Eramsus editions and the Complutensian Polyglot as a type of mutual corroboration.

My suggestion, read the section by Basil E. Hall (1914-1995) in the book Humanists and Protestants, 1500-1900, published 1990.

"Cardinal Jimenez de Cisneros and the Complutensian Bible."

For me it was a real eye-opener on the excellent scholarship, and the window on a time, pre-Trent, when the RCC was doing a very solid NT textual edition.

Steven Avery

Dutchess County, NY, USA

Here's an older example of Scrivener including the Complutensian Polyglot within the TR corpus:

Delete"It is no less true to fact than paradoxical in sound, that the worst corruptions to which the New Testament has ever been subjected, originated within a hundred years after it was composed; that Irenaeus and the African Fathers and the whole Western, with a portion of the Syrian Church, used far inferior manuscripts to those employed by Stunica, or Erasmus, or Stephen thirteen centuries later, when moulding the Textus Receptus." –Scrivener "Intro." Ed. iv Vol. II pp. 264-265

And yes, the initial "closeness" and later use as a "source" by key TR moulders are both primary factors in it being regarded as part of the TR corpus. (As Avery has already explained.)

Thank you Steven!

DeleteThough I wouldn't be comfortable calling the TR "THE" text, it certainly does have an intriguing history.

We do see Erasmus using the Complutensian in his 4th edition, especially for Revelation, 144 places according to Ignacio García Pinilla. And with a cryptic note where he affirms the CP use.

DeleteBeyond that we have from A. J. McDonald with some information on the variants that are different in the CP, he works with the Edward Freer Hills notes.

The World Perceived: Latin Vulgate readings found in the Textus Receptus compared with the Complutensian Polyglot

A. J. McDonald

http://theworldperceived.blogspot.com/2019/11/latin-vulgate-readings-found-in-textus.html

Discussion of Matthew 10:8 "raise the dead", Matthew 27:35, John 3:25, Acts 9:5-6, Acts 20:28, Romans 16:25-27, Rev 22:19 and Acts 8:37 referenced above.

My info can be found here:

Complutensian Polyglot as a Textus Receptus edition - Evangelical Textual Criticism discussion

https://www.purebibleforum.com/index.php?threads/complutensian-polyglot-as-a-textus-receptus-edition-evangelical-textual-criticism-discussion.2376/

There is also the interesting assertion that Stephanus was more influenced by the CP than by the Erasmus fifth edition.

Hum, stuff l didn’t know. I guess that’s why l read this blog. Thank You, Elijah!

ReplyDeleteExcellent post! Very convicting for me as someone who hopes to help people learn more about the Bible and translation. Thank you for the challenge and encouragement!

ReplyDeleteElijah Hixson did a fine job on this post, and especially used the No True Scotsman reference perfectly. He handled it straight-arrow, which is appreciated.

ReplyDeleteAs far as I can tell this little TR edition error began in a YouTube on May, 2020 in a post by Taylor DeSoto, and we discussed it right away on the Facebook forum of Nick Sayers, Textus Receptus Academy.

Textus Receptus Academy

https://www.facebook.com/groups/467217787457422/posts/1013832369462625/

It is possible that Taylor missed the feedback, which I should better have put in the YouTube. (In addition to the Servetus information.)

Most TR and AV defenders are aware of the questions and issue in comparing TR editions.

Edward Freer Hills considered the AV "an independent variety of the Textus Receptus".

And I have been updating this information:

Pure Bible Forum

editions without the heavenly witnesses - Aldine, Gerbelius, Capito, Colines,

https://www.purebibleforum.com/index.php?threads/editions-without-the-heavenly-witnesses-aldine-gerbelius-capito-colines-bebelius.2366/

Steven Avery

Dutchess County, NY USA

Hi Steven, you write:

Delete"As far as I can tell this little TR edition error began in a YouTube on May, 2020 in a post by Taylor DeSoto..."

•DeSoto was extremely tight lipped when I inquired about this, so I can't really make heads or tails of it all. That said, have a look at this 2019 post by Riddle:

"All the classic Protestant printed editions of the TR, for example, include the doxology of the Lord’s Prayer (Matt 6:13b), the traditional ending of Mark, “the only begotten Son” at John 1:18, the PA, Acts 8:37, “God was manifest in the flesh” at 1 Timothy 3:16, the CJ, etc."

•Link:

http://www.jeffriddle.net/2019/11/wm-140-responding-to-which-tr-objection.html?m=1

•Is he uniformed? Did he blunder? Does he not consider Erasmus ¹ ², etc. as "classic?" Who really knows anymore?

Riddle continues:

"First: The various printed Greek editions of the TR should be consulted.

If this is done, one may find that a variant is discovered in only one or two printed editions (perhaps due to a printing error) and a determination can quickly and easily be made in favor of the dominant reading.

The editions which should be primarily consulted are the classic Protestant ones of Stephanus and Beza, based on Erasmus' foundational work. The Elzevir editions should also be consulted, but with the understanding that they appeared after most of the translations of the TR had first been made into the modern languages of Europe."

•He then goes on to reference Erasmus as a witness in his discussion of Rev. 8:1 ("To follow our tentative principles above, we would begin by comparing the printed TRs. I found that Erasmus, like Stephanus, had only το τριτον...I found that Tyndale (1534) follows the reading of Erasmus and Stephanus: “and the third part was turned to wormwood.”") and 2 Pet. 2:1 ("In this case we might also profit from consulting and comparing the printed Greek editions of the TR, where we find again that Erasmus is in harmony with Stephanus.")

•Ironically, I asked him about I John 5:7-8 in the comment section:

Dr. Riddle,

Judging whether I John 5:7-8 should or shouldn't be accepted as authentic is absolutely the same "kind" of critical task (at it's core), regardless of what Textual Principles (or lack thereof) one follows. I'm not understanding your rebuttal of Dr. Jongkind on this point. It's seems as if you are addressing "scale" and even scope, but not "kind". Is it possible that you have conflated the two?

If two readings present themselves, whether in the manuscript tradition or the TR tradition;--and therefore we are left to choose between reading a.) and reading b.) in both cases, the task before us is identical in "kind"...is it not?" - MMR

Riddle's reply:

"MMR,

There is not a debate about 1 John 5:7-8 in the TR."

•Now, I *highly* doubt that I didn't returned fire on this one¹. He likely scrubbed/deleted my response (a habit of his).

•In the end...either way he's confused. (Although, he does get to pick his poison.)

¹ My comment presupposes that there's at least one TR edition that doesn't contain I Jo. 5:7-8!

As do the claims made by Riddle that I was specifically addressing, viz.

"I would counter, to the contrary, that I do not think that the variations in the printed editions of the TR could be said to be equitable (of the same “kind”) with those variations encountered using the modern text critical method. The differences within the printed editions of the TR and the differences within the various modern critical text reconstructions is one both of “scale” AND “kind.”"

Hi Matthew M. Rose,

DeleteYes, Jeffrey Riddle was confused on this edition question and TR consistency in 2019.

My point about Taylor in 2020 was in regard to simply trying to take out the first two editions of Erasmus as non-TR. A bridge way too far!

Steven

“Stephen’s edition of 1550 and that of the Elzevir’s [1624] have been taken as the standard or Received text, the former chiefly in England, the later on the continent…”

ReplyDeleteF. H. A. Scrivener, “A plain introduction to the criticism of the New Testament for the use of Biblical students” (p. 442)

A. J. Macdonald Jr.,

ReplyDeleteDo you have a point?

I ran across an intersting phenomena when looking at the passage on Esword. LITV italicizes the Comma portion of v. 7, but not v. 8. I've seen images of a several 16th and 17th century Bibles which failed to italicize 'earth' in v. 8. I'm not aware of any printed Bible from the first half of the 16th century, in any language other than Latin or its partner in a diglot, in which the entire passage is printed without any text-critical notation.

ReplyDeleteI have updated the post to link to Dr. Riddle's rejoinder and to offer a few brief comments on it.

ReplyDeleteI'm struck by how Riddle uses the word "mature" to distinguish the editions of the TR that he counts. If the TR had to go through a process of maturation to reach its mature and pure form, then that doesn't agree with the belief that this was a text that God by his singular care and providence, kept pure in all ages.

Delete“Kept pure in one age in the editions and translations I like.”

DeleteEric, thanks for this. To me, that editions of the Greek NT didn't get it right until (by providence) they did, has a couple of ramifications: 1. How do we know when they did? Which edition finally 'made it' and got every jot and tittle correct (or, why is it ok to say an edition back then—but not one now—is consistent with 'kept pure in all ages' if it did not get every jot and tittle correct?), and how do we know which edition that is? 2. If providence can work through progressively refining the text then, why can't providence also govern the same thing now?

DeleteSome controversy has erupted over what Dr. Riddle meant when he said that “all those printed editions of the TR” contained certain major disputed passages commonly left out of critical editions of the Greek New Testament.

ReplyDeleteFor my and others’ sakes, here is a transcript of what Riddle said in the interview to which Elijah linked (with a few elements of verbal clutter removed):

--------------------------------

“I like the statement that is put forward by the Trinitarian Bible Society, and I feel—if you’re familiar with the Trinitarian Bible Society, it’s an international Bible society; it’s based in London, and there’s an American office in Grand Rapids, Michigan. But anyway, it’s been around—it actually started as a response to [the] liberalism that was creeping into the Bible societies in England in the 19th century. And the flashpoint was the Trinity. They were having people who were Unitarians who were making translations and working with these Bible societies, and the men who were conservative and orthodox withdrew and founded their own Bible society. [TBS] has a rich heritage of standing for orthodox Christianity [and] trinitarianism. Over the years they[‘ve] stood by the traditional text, the Textus Receptus. They’re the ones who have kept in print Scrivener’s edition of the Greek New Testament.

“So anyway, they [TBS] have a nice statement on their view on Scripture. And in there they say that they believe that the New Testament has been preserved in [a]—I’m not sure if it uses the word ‘family’ or ‘group’ of—printed editions of the TR. And so I think that’s a good way to put it. So sometimes people put forward the so-called ‘Which TR?’ objection. I really think that this objection is overdone. All those printed editions of the TR—all of them included Mark 16:9–20; all of them included John 7:53–8:11; all of them included the doxology of the Lord’s Prayer, Matthew 6:13b; all included the Ethiopian eunuch’s confession in Acts 8:37; all of them included the Comma Johanneum, 1 John 5:7–8. So the differences between them are relatively minor.”

--------------------------------

In context here, “all those printed editions of the TR” appears to be referring to *all of the TR editions named by the Trinitarian Bible Society in their official statement,* approved in 2005. I just checked that statement (screenshot: http://d.pr/gPgWgQ), and that would seem to include “the Complutensian Polyglot, Erasmus[‘]… five editions of the New Testament text from 1516 to 1535, and others [that] were produced by Estienne…, Beza, and Bonaventure and Abraham Elzevir.” (It’s a bit unclear whether they intend to include the Complutensian Polyglot among TR editions, but on balance, I think they do.)

Elijah Hixson pointed out in the post above, with multiple screenshots, that *not* all of those TR editions contained the disputed passages to which Dr. Riddle refers in the above quotation.

Dr. Riddle claimed in a YouTube “rejoinder” (see https://bit.ly/3e08iEH) that he meant “mature, classic, Protestant” editions of the TR—so no Complutensian Polyglot, no editions of Erasmus’ Novum Instrumentum.

There is an apparent difference, therefore, between the views of the Trinitarian Bible Society and those of Dr. Riddle. Dr. Riddle has clarified that those printed GNT editions that were “kept pure in all ages” do *not* include all pre-critical GNT editions but only 1) classic, 2) mature, 3) Protestant ones. That is a helpful clarification. It would be helpful also to receive clarification from TBS as to which pre-critical GNT editions count as TR editions—and therefore which textual differences count as “very minor” (to quote the TBS statement)—and why.

Dear Elijah,

ReplyDeletethank you so much for the corrections, which I have added to my corrigenda. I checked my notes, and found that I was relying here on Hatch, "An Early Edition of the New Testament in Greek" (1941), who writes:

"[…] Sessa's edition contains the Comma lohanneum, which is lacking in the Aldine text. This passage is included also in Bebelius III and Valderus. […] Sessa stands with Bebelius III and Valderus against all the above-mentioned editions in Apoc. 18: 7; and he sides with Erasmus III, Erasmus V, Bebelius III, and Valderus against all the others in including the Comma lohanneum."

I should have checked all the Bebelius editions myself.

Dear Grantley,

DeleteThank you so much for your comment and for showing us what it looks like to correct oneself with integrity. It is an easy mistake and one I have made as well. I wouldn't have even known about many of the relevant editions if it weren't for your work, so thank you so much for it.

Dear Elijah,

DeleteI think I'm the one who should thank you for clearing up this point, and so many others!

"Be sure to talk about the *means* God used to preserve his word, and how having multiple historical documents with variants is *better* than having one document with no historical background." Good advice from a comment above. Bible copyists were human just like Bible translators and Bible teachers, and the Holy Spirit works through all three groups of people even in spite of some pretty major errors sometimes. ("The unrighteous shall inherit the kingdom of God," anyone? 1 Cor. 16:9 in the 1653 KJV.) This is a useful post in that it shows how editions of the Textus Receptus differed from each other in a few major places. But if a person recognizes that the "traditional text" goes back further than 1516 (or 1894) and does not put all his faith in one recent printed edition (which the Bible never told us to do), faith in the preservation of Scripture is not shaken by these differences.

ReplyDeleteThere are a number of noticeable places where the Textus Receptus (at least since Beza) has no, or very little, known Greek manuscript support before 1514, when printing by Ximenez and Erasmus disrupted the hand-copying process by which the Scriptures had been preserved up to that point.

Revelation 16:5 "and shalt be" (none; https://evangelicaltextualcriticism.blogspot.com/2019/12/fact-checking-versional-support-for-ecm.html)

Luke 2:22 "her" (none; https://www.thetextofthegospels.com/2022/04/luke-222-his-or-their.html)

Revelation 22:21 "you all" (none)

Acts 10:6 "he shall tell thee what thou oughtest to do" (none)

Acts 9:5-6 "it is hard for thee to kick against the pricks. 6 And he trembling and astonished said, Lord, what wilt thou have me to do? And the Lord said unto him" (none. Minuscule 629 with Latin influence includes only “σκληρόν σοι πρὸς κέντρα λακτίζειν”, not nearly the whole variant.)

Revelation 5:14 "him that liveth for ever and ever" (GA 2045)

Revelation 4:11 OMITS "our Lord and our God, the Holy One" (GA 2814)

Ephesians 3:9 "fellowship" (GA 2817)

Hebrews 12:20 "or thrust through with a dart" (GA 2815)

Revelation 22:19 "book" (GA 1075, and possibly GA 1957 was before 1516; https://www.thetextofthegospels.com/2019/02/erasmus-manuscript-of-revelation.html)

1 John 5:7-8 "in heaven, the Father, the Word, and the Holy Ghost: and these three are one. 8 And there are three that bear witness in earth" (GA 629, and possibly GA 61 was before 1516, but neither of them has a Greek text that is like that in the TR; both differ in numerous ways from the TR.)

Revelation 21:24 "of them which are saved" (none; but has some similarity to GA 254, GA 2186, and GA 2814)

Revelation 8:7 OMITS "and the third part of the earth was burnt up" (GA 1854, GA 2018, GA 2061, GA 2814)

If anyone knows of *original-language* manuscripts *from before 1516* that I did not list for the non-original printed variant, please let us know!

Some of these textual variants did not exist until about three-quarters of the way through the history of the New Testament text's transmission and preservation. Thank you, Elijah, for publishing this article about how a few editions of the Textus Receptus (and Luther's German Bible) actually have the reading that was preserved through the ages in 1 John 5:7-8, and also thanks to Maurice Robinson for publishing a Greek New Testament with the truly traditional readings in these places.