The following is a guest post from Peter Montoro who is working on a PhD at the University of Birmingham on the NT text of Chrysostom.

Recently, as I was preaching through the Gospel of Matthew

in our church, I came to Matthew 5:21–22, which reads as follows in the

THGNT:

Ἠκούσατε ὅτι ἐρρήθη τοῖς ἀρχαίοις·

οὐ φονεύσεις· ὃς δ’ ἂν φονεύσῃ, ἔνοχος ἔσται τῇ κρίσει·

ἐγὼ δὲ λέγω ὑμῖν ὅτι πᾶς ὁ ὀργιζόμενος τῷ ἀδελφῷ αὐτοῦ

ἔνοχος ἔσται τῇ κρίσει· ὃς δ’ ἂν εἴπῃ τῷ ἀδελφῷ αὐτοῦ·

ῥακά, ἔνοχος ἔσται τῷ συνεδρίῳ· ὃς δ’ ἂν εἴπῃ· μωρέ, ἔνοχος

ἔσται εἰς τὴν γέενναν τοῦ πυρός.

|

| This is not Peter Montoro |

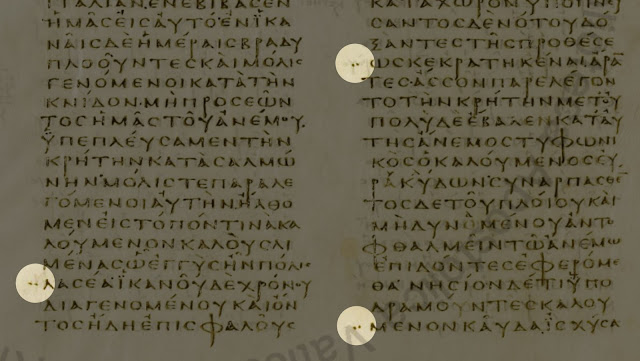

As is well known, a large number of Greek manuscripts read εἰκῆ, “without a cause” or “without true right,” before the second instance

of ἔνοχος ἔσται. Based on the agreement of 01/03 (and most likely P64),

most modern editors (including the THGNT and the NA28) have omitted εἰκῆ in

5:22. The presumed reasoning, explicit in many commentaries, is that the

addition of εἰκῆ is a softening and theologically motivated addition to the

text, an “orthodox corruption” as it were. Metzger, for example, has this to

say in his textual commentary:

Although the reading with εἰκῇ is widespread from the second

century onwards, it is much more likely that the word was added by copyists in

order to soften the rigor of the precept, than omitted as unnecessary.

However, based on patristic discussion of the variant in

Origen and Jerome (as found in Amy Donaldson’s excellent dissertation), a

motivated reading seems to have been far more likely in the other direction—it

was the suggestion that some anger might be permissible that Origen and Jerome

found to be problematic, not the reverse. See for example, this discussion by

Origen:

Since some think that anger sometimes occurs with good

reason because they improperly add to the Gospel the word ‘without cause’ in

the saying, ‘Whoever is angry with his brother will be liable to judgement’

(Matt. 5:22)—for some have read, ‘Whoever is angry with his brother without

cause’—let us convince them of their error from the statement under discussion

which says, ‘Let all bitterness and wrath and anger and clamour and blasphemy

be removed from you.’ For the term ‘all’ here clearly applies to all the nouns

in common, so that no bitterness is allowed, no wrath is permitted, and no

anger occurs with good reason. It is said in the thirty-sixth Psalm, since all

anger is sin (and likewise also wrath), ‘Cease from anger, and leave wrath’

(Ps. 36:8). It is never possible, therefore, to be angry with someone with good

reason. [Donaldson, 352, citing from Heine’s edition 205–206]

As can easily be seen in this discussion (and even more

clearly in Jerome’s repeated discussions of this passage), while we moderns may

assume that the early church would have wanted to soften Jesus’s

teaching, the evidence points instead, in this and many other areas as well,

rather toward a tendency to strengthen it, to remove exceptions,

rather than to add them (this can be seen very clearly in the

overall attitude toward remarriage, even after the death of a spouse).

I therefore decided to take a fresh look at the available

textual evidence. A consideration of the Text und Textwert (TuT) data suggests another explanation

for this textual variation altogether. No less than 21 of the manuscripts

classed as Koinehandschriften, including some that agree at the 97 and 98%

(e.g., 045) levels have exactly the same omission that is found in the

early witnesses 01 and 03. Since there are 64 Teststellen in Matthew, a 98%

agreement means that this is the only Teststelle where this

manuscript differs from the majority.

As Holger Strutwolf explained in his recent paper at the

CSNTM conference (though of course he was dealing with examples from Mark, not

Matthew), this sort of pattern rather strongly suggests that a particular

variant emerged multiple times, and is therefore best explained, not as a

theologically motivated reading, but rather as a simple scribal mistake.

As it turns out, there is a rather simple explanation for

the omission of εἰκῆ, one that fits perfectly with the sort of mistakes that

scribes, early as well as late, are known to make. The sequence ἔνοχος

ἔσται occurs no less than four times in Matt 5:21–22, both before and after

the variation unit in question. Because this second instance (if εἰκῆ is

indeed original) is the only one that breaks the pattern, it would have been a

relatively simple mistake to unintentionally harmonize it to the repetitions of

this same pattern found in the immediate context, the same sort of change we

see over and over again in manuscripts from every period.

On the other hand, there does not seem to be a

straightforward way to explain the addition of this word as a scribal mistake.

Since the TuT evidence makes it very clear that the omission did

in fact occur in late Byzantine manuscripts that are extremely unlikely to have

experienced theologically motivated change, it makes much more sense to see the

omission of this word in early manuscripts as resulting from the same sort of

scribal mistake that we know to have taken place later.

Furthermore, as David Alan Black pointed out a number of

years ago, this very

same chapter of Matthew’s Gospel contains two other examples (ψευδόμενοι in

5:11 and παρεκτὸς λόγου πορνείας in 5:32) of very similar clarifying

qualifiers.

While this is only a brief preliminary investigation, it

seems to be at this point to be likely that the omission of εἰκῆ should be

seen as an early scribal mistake rather than as an example of an “obvious”

orthodox corruption.