Thursday, August 23, 2018

SNTS Athens Response

Recenty I blogged about the three sessions in the text-critical seminar at the SNTS meeting in Athens which I chaired with Claire Clivaz. On the last day I responded to Juan Hernandez, who has subsequently urged me to post my Powerpoint. I have now uploaded a PDF of my powerpoint for download here if anyone is interested.

Tuesday, August 21, 2018

Ninth century prequels to our current chapter system

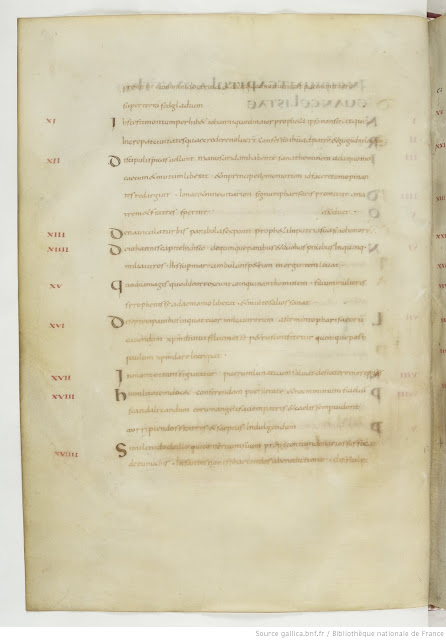

The story is often told of how our chapter divisions go back to Stephen Langton in the early thirteenth century. That’s true enough, but it’s worth noting sometimes how close even earlier divisions can get to our current ones. Here’s BnF Ms 268 from the late 8th/early 9th century.

It’s listing the sections of Matthew. I’ve chosen this page because it’s a particularly good example, but it lists ‘chapters’ 11 to 20 (the first x of xx/20 is no longer visible) of Matthew. The surprising thing is that when we look at the content of each chapter, we see that it only misses our current chapter beginnings for ‘chapters’ 16 and 19.

So what Langton really achieved was to produce a standard system where one had not existed previously.

It’s listing the sections of Matthew. I’ve chosen this page because it’s a particularly good example, but it lists ‘chapters’ 11 to 20 (the first x of xx/20 is no longer visible) of Matthew. The surprising thing is that when we look at the content of each chapter, we see that it only misses our current chapter beginnings for ‘chapters’ 16 and 19.

So what Langton really achieved was to produce a standard system where one had not existed previously.

The ninth century BnF Ms 265 is similar:

Monday, August 20, 2018

History and Development of the Nestle-Aland Editions Funded

Good news out of Münster today. Greg Paulson has received funding to study the history and development of the Novum Testamentum Graece editions. Congrats, Greg! Now, how do I apply to be a research assistant for this?

Here’s the announcement:

Here’s the announcement:

Friday, August 17, 2018

Where Orthography Affects the New Testament Text

Beginning Greek students are often shocked when they discover the gap between the formatting of their modern, printed New Testaments and our earliest Greek New Testament manuscripts. The letters are all “uppercase,” there are few if any spaces between letters, accents and breathing marks are nowhere in sight, iotas aren’t written subscript, and punctuation is rare as well.

Having now been introduced to scriptio continua, the first question they ask is usually “How on earth could they read it?” This is quickly followed by two more questions: “Then who decides where to put all these things in our print editions and doesn’t the decision affect interpretation?” Last year I found myself telling my first-year students that editorial decisions about formatting only rarely affect interpretation (cf. Mark 4.3; Rom 9.5; Eph 5.21–22).

This is probably true in the grand scheme of things. But, almost as soon as I said it, I knew there must be far more examples than I’m actually familiar with. In prepping for a new Greek class this semester, I wanted to close the gap on my ignorance. So, I started compiling a list of places where matters of orthography—especially punctuation, accenting, spelling, and word division—affect the translation or interpretation.

Having now been introduced to scriptio continua, the first question they ask is usually “How on earth could they read it?” This is quickly followed by two more questions: “Then who decides where to put all these things in our print editions and doesn’t the decision affect interpretation?” Last year I found myself telling my first-year students that editorial decisions about formatting only rarely affect interpretation (cf. Mark 4.3; Rom 9.5; Eph 5.21–22).

|

| Rom 9.5 in P46 |

Thursday, August 16, 2018

Museum of the Bible and Dirk Obbink

Somehow I missed this, but back in June, Michael Press wrote an article exploring the latest mandatory tax filing from the Museum of the Bible. Most of the payments are not terribly surprising although Press sees problems with some of the locations of their funded digs. He seems most troubled that the Museum is Evangelical and influential.

Of most interest to me is the end of the article which explains payments to one particular individual associated with the Oxyrhynchus collection. Press suggests that the unnamed “Domestic Individual” is Dirk Obbink, and that certainly makes the most sense. It’s not actually news that he was paid by them (see here), but now I guess we know how much. According to the tax filing, it was $225,311 in 2016/2017. (Who says textual criticism doesn’t pay?)

Of most interest to me is the end of the article which explains payments to one particular individual associated with the Oxyrhynchus collection. Press suggests that the unnamed “Domestic Individual” is Dirk Obbink, and that certainly makes the most sense. It’s not actually news that he was paid by them (see here), but now I guess we know how much. According to the tax filing, it was $225,311 in 2016/2017. (Who says textual criticism doesn’t pay?)

Press suggests that the payments might be what confused people into thinking the Museum owned P.Oxy. 5345 (previously “First-Century Mark”). That seems unlikely to me since paying for research on a fragment is hardly the same thing as owning it. Also, why would anyone sign an NDA with the people funding the research rather than with the institution that actually owns the object of that research? These questions persist.

Here is what Press has to say about the payment:

Of most interest to me is the end of the article which explains payments to one particular individual associated with the Oxyrhynchus collection. Press suggests that the unnamed “Domestic Individual” is Dirk Obbink, and that certainly makes the most sense. It’s not actually news that he was paid by them (see here), but now I guess we know how much. According to the tax filing, it was $225,311 in 2016/2017. (Who says textual criticism doesn’t pay?)

Of most interest to me is the end of the article which explains payments to one particular individual associated with the Oxyrhynchus collection. Press suggests that the unnamed “Domestic Individual” is Dirk Obbink, and that certainly makes the most sense. It’s not actually news that he was paid by them (see here), but now I guess we know how much. According to the tax filing, it was $225,311 in 2016/2017. (Who says textual criticism doesn’t pay?)Press suggests that the payments might be what confused people into thinking the Museum owned P.Oxy. 5345 (previously “First-Century Mark”). That seems unlikely to me since paying for research on a fragment is hardly the same thing as owning it. Also, why would anyone sign an NDA with the people funding the research rather than with the institution that actually owns the object of that research? These questions persist.

Here is what Press has to say about the payment:

Besides funding institutions, the Museum of the Bible also reports grants to individuals — most of which are non-itemized scholarships. One grant, however, is itemized in some detail: in 2016–2017, the museum awarded $225,311 to an unnamed individual as a “research grant for Early Christian Lives, Proteus/Ancient Lives, and Imaging Papyri projects as well as establishing a research center.” All of these projects involve the Oxyrhynchus papyri, the largest group of papyrus documents from the ancient world. They consist of fragments of several hundred thousand texts from an ancient garbage dump at the site of Oxyrhynchus (modern Al Bahnasa) in Egypt. Most of the papyri were found in excavations at the site in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, conducted on behalf of the Egypt Exploration Society (EES) in the U.K. The Museum of the Bible purchased several Oxyrhynchus papyri that had been gifted to American institutions in the early 20th century and later deaccessioned. However, most of the papyri from the site are still owned by the EES and housed at the University of Oxford.

The unnamed individual who received the grant from the Museum of the Bible is presumably Dirk Obbink, an American-born papyrologist currently at the University of Oxford. Obbink is the principal investigator for all of the projects named on the Form 990. Obbink’s relationship with the museum has been public for years, though the exact nature of it has never been clear. Obbink is listed as Papyrus Series editor for the museum’s publications with the prominent Dutch academic publisher Brill, and has been paid by the museum as a consultant, but in comments to Megan Gannon of Live Science in 2015, Obbink suggested that the Greens had more direct control over his work. Unlike many other collaborations, this arrangement was never made public — there is no press release on the Museum of the Bible website. It was also unusual in that the grant was made to an individual rather than an institution. (In a statement to Hyperallergic, the EES declared that “the EES has not, and has never had, any arrangement of any kind with the Museum of the Bible.”)

This funding arrangement may shed some light on the issue of the rumored “First Century Mark.” Starting in 2012, rumors circulated among biblical scholars of a fragment of the New Testament Gospel of Mark dating to the first century CE. This rumored First Century Mark would be significant as the earliest known version of the text, and one dating shortly after the book would have been written (it is generally dated by scholars sometime in the middle decades of the first century CE). It was thought that the Green family owned or was trying to purchase this fragment, but no firm evidence was ever put forward about this. Last month, the EES posted a note about a recently published Oxyrhynchus papyrus, confirming that this was in fact the rumored First Century Mark — except that it dated to the late second or early third century, and was owned not by the Museum of the Bible but by the EES. The publication of the fragment was edited by Dirk Obbink. The Museum of the Bible’s funding of Obbink’s Oxyrhynchus projects might have some bearing on puzzling aspects of the case, such as why it was believed that the fragment was owned by the Museum of the Bible. (If in fact the Green family is spending hundreds of thousands of dollars funding Oxyrhynchus-related research, then they may have a proprietary attitude toward that research even if they do not own the fragments themselves.)

Tuesday, August 14, 2018

INTF’s New Blog

The INTF has set up a new blog! Although we have featured blogs on our site before (as “Personal Blogs”), our newly implemented Liferay portlet called “Blog” aims to create a centralized portal for offering regular updates on the happenings of the institute and its projects as well as other things that are related (at least tangentially) to New Testament textual criticism.Welcome to the blogosphere! I have added them to our blogroll in the sidebar.

Just to offer one tidbit before our next post, in case you were unaware, there is a paleography database (compiled by Marie-Luise Lakmann) that may be useful for those of you who are transcribing Greek manuscripts: http://intf.uni-muenster.de/NT_PALAEO/. To get started, click on “Suche” on the left-hand column.

Subscribe to:

Posts

(

Atom

)

Loading...