Today at SBL, I will be giving a paper in a special section on the 75th anniversary of The International Greek New Testament Project. Revisiting their website reminded me that the IGNTP set up a YouTube channel not long ago and it is full of videos. Today seemed like a good day to remind our readers of this great resource. Go check it out.

Volume 28 (2023)

Articles

- Juha Pakkala, The Rebuilding and Settlement of Jerusalem in Ezra-Nehemiah and 1 Esdras (pp. 1–18)

-

Abstract: This paper reviews Dieter Böhler’s theory about the conception of Jerusalem in MT Ezra Nehemiah and 1 Esdras. According to Böhler, 1 Esdras preserves earlier versions in variants dealing with the rebuilding and settlement of Jerusalem, while the MT was revised to accommodate Ezra (and Neh 8) to the Nehemiah story. This paper argues that Böhler’s theory is highly unlikely. It is based on things lacking in the MT, while there is little positive evidence for the theory in the MT variants. The theory also neglects many passages that contradict the conception of an unsettled and unbuilt Jerusalem before Nehemiah. Textual variants used in favor of the theory are often controversial, heavily edited, and/or the result of textual corruption. In none of the cases does 1 Esdras unambiguously preserve the original reading. A conceptional connection between the MT variants remains unclear or is based on the variants in 1 Esdras. The 1 Esdras variants are connected by Jerusalem, its physical spaces, and temple gates. This may be an attempt to highlight the accomplishments of the Davidic Zerubbabel, which fits well with the anti-Hasmonean stand of 1 Esdras. Nehemiah and his accomplishments (such as references to the wall) were omitted because he was a non-Davidic leader whose memory 1 Esdras sought to eradicate.

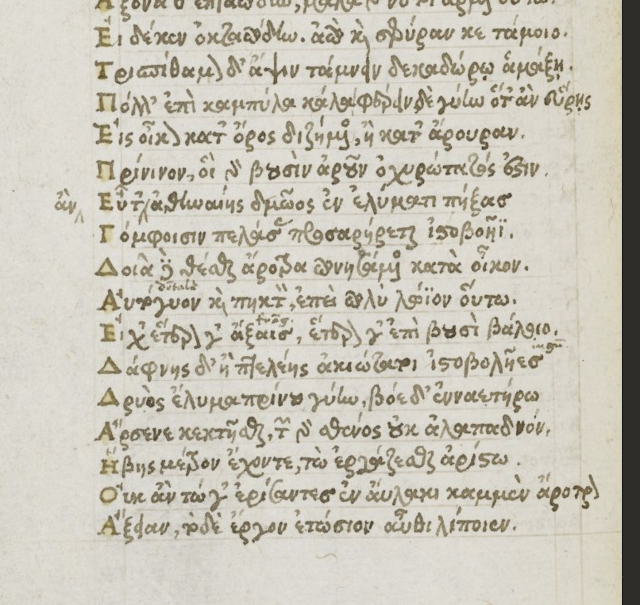

- Zachary J. Cole, Eunike C. Bentson, and Randall M. Shandronski, Scribal Corrections in Early Greek New Testament Manuscripts: The Fragments (pp. 19–41)

-

Abstract: This study catalogs and categorizes the scribal corrections found in the earliest fragmentary Greek New Testament manuscripts (second–fourth/fifth centuries). Although corrections are normally identified and discussed by manuscript editors, this analysis gathers such evidence from a wide range of artifacts in order to observe relevant trends in scribal habits across the group as a whole. Corrections are identified in the earliest 114 fragmentary manuscripts of the New Testament, including papyri and parchment. These corrections are then categorized and discussed, with attention given to the copying process, text-critical evidence, and the identity of the correctors.

- Régis Burnet and Claire Clivaz, The Freer-Logion (Mark 16:14): GA 032, Jerome, and Erasmus (pp. 43–65)

-

Abstract: As regularly noted, the Freer-Logion has not often been studied until today. Its reference by Jerome in Pelag. 2.15 is mentioned, but New Testament scholars have overlooked its first modern commentator, Erasmus, until three 2022 and 2023 articles by Krans, Yi, and Burnet. As a next step, this article presents the first French and English translations of the complete Annotationes of Erasmus on Mark 16:14 next to the Latin text edited by Hovingh (2000). We demonstrate that his philological notes are particularly fruitful for understanding the history of Mark’s ending. Using the term coronis, in the sense of the end of a given unit, Erasmus asserts that the sentences quoted by Jerome have been inserted into chapter 16 and may have come from an apocryphal source. We suggest that the addition after Mark 16:3 in VL 1 can also be seen as a coronis inserted in Mark 16. Finally, we discuss the κορωνίς drawn at the end of Mark in GA 032: this editorial decoration adds supplementary evidence for a fifth-century date for the copy of Mark in W, as proposed by Orsini (2019).

- Richard G. Fellows, Early Textual Variants That Downplay the Roles of Women in the Bethany Account (pp. 67–82)

-

Abstract: It has been suggested that a number of textual variants in the Bethany account in John 11:1, 2, 3, 5; 12:2 suggest that Martha was not originally present but was interpolated at a later stage to minimize the importance of Mary. This article will argue that these variants are best explained not by a theory of interpolation but by a general tendency to downplay the role of women and by subsequent attempts to harmonize the text to the immediate context. In particular, we will see that an alteration to 11:1 defined Martha by her relationship to her male relative (Lazarus) rather than to her sister Mary and inadvertently created tensions with 11:2–3. This led to later adjustments that we see in the text, in particular in P66. This article makes a contribution to the subject of textual variants that suppress women, a topic that will require more research in the future.

- Lorne R. Zelyck, Bernard Pyne Grenfell: Papyrologist, Professor, "Lunatic" (pp. 83–110)

-

Abstract: The purpose of this article is threefold. First, it provides biographical information about B. P. Grenfell and his afflictions by narrating multiple episodes of incarceration in lunatic asylums, based on his medical records and available archival material. Most readers of this journal have benefited from Grenfell’s scholarship and studied the texts he and A. S. Hunt edited, but few are aware of the severity of his illness. Second, it attempts to clarify the nature of this illness and its effect on Grenfell’s career and collegial relationships. One scholar has claimed that Grenfell was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia, but a comparison with modern psychiatric diagnostic guides suggests that his episodes of psychosis may have been the result of a mood disorder or a multitude of other ailments. A brief portrait of British insane asylums in the 1900s and the societal perception of their patients helps explain the dissolution of Grenfell and Hunt’s harmonious relationship. Last, this article briefly addresses current mental health concerns within the academy and makes a modest appeal for empathy and compassion toward our colleagues who suffer with mental health problems. By discussing the nature and severity of Grenfell’s illness in light of his accomplishments, this article seeks to diminish the stigma surrounding mental illness in the academy.

- Alan Bunning, The First Computer-Generated Greek New Testament (pp. 111–126)

-

Abstract: A plausible Greek New Testament text can be automatically generated by a computer program using statistical analysis and algorithms that weigh the earliest manuscript data in a manner simulating a reasoned-eclecticism approach. This method offers several substantial advantages by providing a consistently weighed text that is openly transparent, without any theological bias, and scientifically reproducible, and the results are very similar to our best modern critical tests. This initial accomplishment could have a number of future implications for the field of textual criticism regarding advances in the use of statistics and algorithms for further refinements in the production of critical texts

Special Feature

- Andrew J. Patton and Clark R. Bates, Special Feature: Decentralizing the Biblical Text in Greek New Testament Manuscripts (pp. 127–130)

-

Abstract: The editors introduce the five articles in the special section of the current volume. These papers were first presented at a workshop at the University of Brimingham.

- Andrew J. Patton, Unchaining the Scriptures (pp. 131–148)

-

Abstract: Ugo Rozzo quipped, “it should also be obvious that the paratext is not the text (even if it is a text).” His sentiment certainly is reflected in most Greek New Testament manuscripts: the page focuses on the scriptures, and paratexts serve the reader in navigating, understanding, and appreciating the sacred words. Determining paratextual relationships in Greek New Testament manuscripts with catenae is more complicated because of the presence of a second extensive text in the same codex. This article explores the relationship between the scriptures and the catenae in manuscripts of the gospels. It proposes that some catena manuscripts reverse the usual text-paratext relationship and decentralizes the biblical text, including it as a reference for the commentary. The format of the constituent elements within a manuscript does not alone suffice to determine the paratextual relationships in commentary manuscripts.

- Jeremiah Coogan, Doubled Recycling: The Gospel according to Mark in Late Ancient Catena Commentary (pp. 149–165)

-

Abstract: In the late ancient Mediterranean, biblical commentary often took citational form through the creation of catenae. The citational gesture of such projects deployed the authority of tradition and embedded the biblical lemma within an interpretative frame. Late ancient catenae for Matthew, Luke, John, and other biblical texts reconfigured prior commentary. Yet because Mark lacked a commentary tradition, one could not use existing commentaries on Mark to construct a catena. The absence prompted an innovative form of recycling: the sixth-century Catena in Marcum repurposed commentary on Matthew, Luke, and John in order to create a novel catena for Mark. This double act of recycling reappropriated existing commentary for a new text. The resulting catena embedded Mark within a fourfold tradition of gospel commentary, underscoring narrative and theological tensions between Mark and other gospels. Since similar tensions and ruptures attend other commentarial projects as well, the Catena in Marcum illuminates the broader practice of recycling in commentary.

- Saskia Dirkse, New Treasures as Well as Old: The Use and Reuse of the Gospel Kephalalaia in Commentary Manuscripts (pp. 167–182)

-

Abstract: This article looks at one of the oldest and most stable Greek gospel paratexts, the kephalaia (known also as the Old Greek Chapters) and their use in gospel commentary manuscripts. Although their original purpose remains the subject of speculation, the kephalaia fulfill various practical functions, acting as a bookmarking tool through the marginal placement of titloi and as an exegetical lens, since each kephalaion brings into focus one particular event or theme of the gospel story. As part of the standard paratextual furniture of gospel books since antiquity, the kephalaia also appear in many gospel commentaries, usually in unaltered form, where they also operate as structuring elements for the lemmata or as section headings for the ensuing commentary text. A few commentary manuscripts, however, feature kephalaia lists that are greatly expanded and specially adapted to the commentary text. This article will focus on one particular set of commentary kephalaia attested in three manuscripts and examine the additions, alterations, and refinements that the standard lists and titloi undergo to suit them to the commentary’s contents. It will also consider how an expanded kephalaia system might affect the reader’s approach to both the biblical and the commentary text in a way that differs from how the kephalaia mediate the text in a standard gospel manuscript.

- Tommy Wasserman, Marginalized Manuscripts of the Greek New Testament in Vienna (pp. 137–191)

-

Abstract: According to the current version of the official register (Kurzgefasste Liste), there are currently ninety-eight Greek New Testament manuscripts housed in the National Library of Austria in Vienna. Resulting from work on this article, three of these manuscripts have been registered and assigned a Gregory-Aland number: two lectionaries (GA L2530, L2531) and one minuscule (GA 3010). A fourth item, one leaf from a commentary manuscript glued into MS Theologicus gr. 164, has not yet been registered in the Liste. Finally, a fifth item, MS Theol. gr. 209, a miscellaneous manuscript, contains a lectionary (GA L155) and a commentary on Matthew that was registered as GA 2988 quite recently (fols. 56r–143v). In my opinion, the first part of this fifth codex, copied from another exemplar with a different commentary on Matthew (fols. 1–55v), also qualifies for inclusion in the Liste as part of GA 2988. In this first commentary, the text from Matthew has been abbreviated at times—an example of how the biblical text has been decentralized in a commentary manuscript (a feature that is not uncommon). In fact, in all these manuscripts, the New Testament text has been marginalized in favor of other textual or codicological features, which has arguably worked against their registration in the Liste

- Clark R. Bates, Materializing Unity: Catena Manuscripts as Vessels for Imperial and Ecclesial Reform (pp. 193–206)

-

Abstract: Ecclesial divisions following the christological controversies of the Council of Chalcedon in the fifth century and leading into the Council of Trullo in the seventh century provide a cultural backdrop for the creation of catenae and offer a potential explanation for how catenae were used in the development and promulgation of a syncretic Byzantine theology. During the reigns of both Justinian I (527–565) and Justinian II (685–695/705–711) attempts were made to unite the divisions within the Greek church—each for divergent purposes. Justinian I established a precedent in legal matters by consolidating the numerous Roman legal codes into a single volume, intended to supersede all previous tomes and become the singular reference source for all discussion. He expressed similar interests in seeking to unite the Byzantine church under a single christological perspective. By the first reign of Justinian II, the Council of Trullo was convened. Within the acts of the council, we read Canon 19, which declares that all clergy are to teach piety and defend the scripture only with the words of the orthodox divines and not from one’s own intellect. This marks a second attempt to unite the church, but this time through the authority of the past. This paper will draw upon historical data to parallel the development of the New Testament catena manuscript tradition, proposing that these manuscripts served as a reference point for clergy, particularly post-Trullo, to preach piety and defend orthodoxy to the confessional community.

Reviews

- James Barker, Tatian's Diatessaron: Composition, Redaction, Recension, and Reception (Ian N. Mills, reviewer) (pp. 207–211)

- Alessandro Bausi, Bruno Reudenbach, and Hanna Wimmer, eds., Canones: The Art of Harmony. The Canon Tables of the Four Gospels (Thomas J. Kraus, reviewer) (pp. 213–215)

- Georgi Parpulov, Middle-Byzantine Evangelist Portraits: A Corpus of Minature Paintings (Thomas J. Kraus, reviewer) (pp. 217–219)

- Daniel Patte, Romans: Three Exegetical Interpretations and the History of Reception, vol. 1: Romans 1:1-32 (Manuel Nägele, reviewer) (pp. 221–226)

- Josef Schmid, Studies in the History of the Apocalypse: The Ancient Stems (Thomas J. Kraus, reviewer) (pp. 227–229)