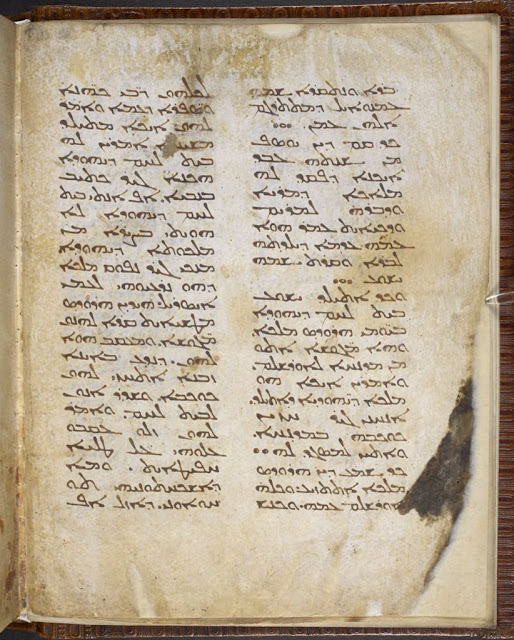

I learned some good news by way of Ian Mills on Twitter today. The British Library has now digitized Add MS 14451, better known as the Curetonian Syriac Gospels. There are a handful of leaves in other places as well (see here). The images from the BL are listed as in the public domain.

Showing posts with label British Library. Show all posts

Showing posts with label British Library. Show all posts

Friday, June 30, 2023

Wednesday, January 09, 2019

A Greek Witness to the Lord’s Prayer, Written in Latin Letters, without the Doxology

Yesterday, I wrote that I would devote a full post to what was one of my favourite items in the Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms exhibition at the British Library.

The catalogue entry gives it the title “The earliest Durham gospel-book”, not to be confused with the Durham Gospels (also on display, by the way).

The manuscript, of which only thirteen folios survive, contains bits of Matthew and Mark in Latin written in the mid-seventh century. Folios are spread across three volumes in the Durham Cathedral Library, but the one on display is MS A.II.10. The text is mostly Vulgate, but Mark 2:12–6:5 are Old Latin (VL 19A). Hugh Houghton writes that its text there corresponds “to the text of the Gallo-Irish subgroup seen in VL 14” (Latin New Testament, p. 221).

|

| Source: Wikipedia |

What makes this manuscript so interesting to me, however, is that it contains the Lord’s Prayer written in Greek but in Latin characters. It is difficult to see, but it’s there in the two lower D-shaped panels.

Now this raises the question to me: should the INTF give it a GA number?

It’s clearly not an amulet or an ostracon, and it’s not written on wood, wax or anything like that. Although it is not strictly a continuous-text manuscript, it does occur between Matthew and Mark in a continuous-text manuscript. It isn’t really analogous to a liturgical manuscript because this bit of text is not located within the context of its place in the liturgy; it’s just there.

If P42 can be P42 though it is a Greek-Coptic book of the Odes, then why can’t this manuscript have its own GA number? It is a Greek-Latin continuous-text manuscript of the Gospels, even if the Greek bit lacks an accompanying Latin parallel, is limited to this one selection and is written in Latin characters rather than in Greek.

Perhaps of greater interest to readers is that, unless I’m mistaken (the text is admittedly difficult to see and my complete inexperience reading Greek in 7th-century Latin transliteration), it appears to lack the doxology of Matt. 6:13. In the second-to-last line, I see puniro (πονηροῦ) followed by what look like a couple of nomina sacra. I also see curion (κύριον) in that last line. Thus, not only is there not room for the doxology, the text that is there seems to be a different kind of ending to the prayer than the traditional doxology (I will happily let any readers spend more time than I did trying to decipher the full text).

What can we make of this? It is a Greek witness to the Lord’s Prayer without the doxology from either Iona or Northumbria in the mid-seventh century. Should it have a GA number? Should it be considered among textual witnesses for that variant?

Tuesday, January 08, 2019

Cats, Bibles and More at the British Library

Over the weekend, I made a trip to the British Library and got to see an amazing exhibit: Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms: Art, Word, War. This exhibition is open until 19 February 2019 and features some amazing manuscripts:

As exciting as that exhibition is, I am sure that all of our readers would be interested in another exhibition, Cats on the Page, because who doesn’t love cats? This one is free, and best of all, if you are coming to the UK for the Birmingham Colloquium on the Textual Criticism of the New Testament (4–6 March 2019), you can make it to this exhibition. It is open until 17 March 2019.

To be clear, Cats on the Page did not feature any manuscripts with paw prints on them, but the British Library’s Medieval Manuscripts Blog has a recent post about those manuscripts, with several images. There is also this book, if you need more cats and manuscripts. The exhibition did feature an anti-witchcraft pamphlet from around 1579 with something about a cat in it. There were also a few bizarre recordings that you could listen to, including one of a musical duet featuring two singers meowing at each other, and another that was just sounds of a cat hissing. Fun for children though, for sure.

Does anyone know if there are any manuscripts of the Bible with cat prints on them? Has CSNTM digitised any?

I went to the Cats on the Page exhibit mainly because we had to wait a little while before we could go to the Anglo-Saxon exhibit (and also because cats). If you only have time for one—as much as I’m sure you would be tempted to see the cat exhibit, you should definitely skip it in order to see Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms: Art, Word, War.

We booked our tickets to Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms on the train on the way down, and it had sold out by the time we arrived at the British Library. It truly is an amazing exhibit. If you are remotely in the area, it is absolutely worth a trip. I cannot recommend it highly enough. It took me over an hour to get through, and that was because I had to rush through a lot of it due to having two small children with us. I could have easily spent two hours or longer there.

The exhibition has some of the “greatest hits” of manuscripts connected to the British Isles from way back when. You are met in the first room with The St. Augustine Gospels, one of the books Augustine of Canterbury brought with him on his mission to the English in 597. Other famous Bibles on exhibit include the Lindisfarne Gospels, the St. Cuthbert Gospel, the Harley Golden Gospels, the Coronation Gospels, the Utrecht Psalter, and its copy, the Harley Psalter, the **massive** Codex Amiatinus. There are even a couple of folios of purple parchment from the Stockholm Codex Aureus. You can imagine how I was about as excited as a 4-year-old in a candy store when I turned the corner to see purple parchment. The mood was somewhat dampered when my actual 4-year-old decided to argue with me on the grounds that it was more reddish than purple. In the end, I conceded her point.

Codex Amiatinus (good stuff from the BL here) is especially significant. It was produced at Wearmouth-Jarrow (up near Newcastle) in the early 8th-century—one of three massive single-volume Bibles. It is the only one that has survived, and this is the first time it’s been back to Britain in 1300 years, having been excellently cared-for in Italy through the centuries. What I was shocked to see, however, was that in the middle of the room a few feet from Codex Amiatinus was a less-imposing display of a few pages. These were the Middleton leaves (BL, Add Ms 45025)—some of the few folios that remain of one of the other two volumes made with Codex Amiatinus. Not only do we have Codex Amiatinus in Britiain for the first time in 1300 years, but we have it on display next to the remains of one of its two siblings.

There is also an element of shock to see the tiny St. Cuthbert Gospel and the massive Codex Amiatinus next to each other. Two copies of the Scriptures made near to each other in time and location, yet their outward appearances look nothing alike.

The exhibition features not just biblical manuscripts, either. You can also see the only copy of Beowulf, the earliest copy of the Rule of St. Benedict, and the Great Domesday Book (as well as the Exon Domesday). A number of non-book items are of interest as well, but again, I had to rush through parts of it.

Perhaps one my unexpected favourites of the exhibition was another manuscript. I will post more on it tomorrow morning as it deserves its own discussion.

My only criticism (and I feel guilty for having any criticism at all for this excellent exhibit) is that I would have liked to see f. 1 of BL, Cotton MS Titus C XV. The other four folios are from the 6th-century purple codex N022, but f. 1 has a papyrus fragment of Gregory the Great’s Forty Homilies on the Gospels in Latin that dates right to around the time of the composition of the work itself. Robert Babcock wrote a delightful article a few years ago in which he identified the fragment and speculated (reasonably in my opinion) that it might have been one of the other books Augustine of Canterbury brought with him to Britain in 597. It would have been nice to see it next to the St. Augustine Gospels (though there is a nice image of the fragment on p. 21 of the exhibition catalogue).

It is also always a treat to see some of the treasures of the British Library that are on permanent display, like Codex Sinaiticus, the earliest complete copy of the New Testament.

In summary, drop what you’re doing and go see this amazing exhibit, but be sure to book in advance.

More to come tomorrow.

Treasures from the British Library’s own collection, including the beautifully illuminated Lindisfarne Gospels, Beowulf and Bede’s Ecclesiastical History, sit alongside stunning finds from Sutton Hoo and the Staffordshire Hoard. The world-famous Domesday Book offers its unrivalled depiction of the landscape of late Anglo-Saxon England while Codex Amiatinus, a giant Northumbrian Bible taken to Italy in 716, returns to England for the first time in 1300 years.Here is a 30-second promo for the exhibition:

As exciting as that exhibition is, I am sure that all of our readers would be interested in another exhibition, Cats on the Page, because who doesn’t love cats? This one is free, and best of all, if you are coming to the UK for the Birmingham Colloquium on the Textual Criticism of the New Testament (4–6 March 2019), you can make it to this exhibition. It is open until 17 March 2019.

|

| Source: I took this photo (no photography permitted in the exhibit) |

Does anyone know if there are any manuscripts of the Bible with cat prints on them? Has CSNTM digitised any?

I went to the Cats on the Page exhibit mainly because we had to wait a little while before we could go to the Anglo-Saxon exhibit (and also because cats). If you only have time for one—as much as I’m sure you would be tempted to see the cat exhibit, you should definitely skip it in order to see Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms: Art, Word, War.

We booked our tickets to Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms on the train on the way down, and it had sold out by the time we arrived at the British Library. It truly is an amazing exhibit. If you are remotely in the area, it is absolutely worth a trip. I cannot recommend it highly enough. It took me over an hour to get through, and that was because I had to rush through a lot of it due to having two small children with us. I could have easily spent two hours or longer there.

The exhibition has some of the “greatest hits” of manuscripts connected to the British Isles from way back when. You are met in the first room with The St. Augustine Gospels, one of the books Augustine of Canterbury brought with him on his mission to the English in 597. Other famous Bibles on exhibit include the Lindisfarne Gospels, the St. Cuthbert Gospel, the Harley Golden Gospels, the Coronation Gospels, the Utrecht Psalter, and its copy, the Harley Psalter, the **massive** Codex Amiatinus. There are even a couple of folios of purple parchment from the Stockholm Codex Aureus. You can imagine how I was about as excited as a 4-year-old in a candy store when I turned the corner to see purple parchment. The mood was somewhat dampered when my actual 4-year-old decided to argue with me on the grounds that it was more reddish than purple. In the end, I conceded her point.

Codex Amiatinus (good stuff from the BL here) is especially significant. It was produced at Wearmouth-Jarrow (up near Newcastle) in the early 8th-century—one of three massive single-volume Bibles. It is the only one that has survived, and this is the first time it’s been back to Britain in 1300 years, having been excellently cared-for in Italy through the centuries. What I was shocked to see, however, was that in the middle of the room a few feet from Codex Amiatinus was a less-imposing display of a few pages. These were the Middleton leaves (BL, Add Ms 45025)—some of the few folios that remain of one of the other two volumes made with Codex Amiatinus. Not only do we have Codex Amiatinus in Britiain for the first time in 1300 years, but we have it on display next to the remains of one of its two siblings.

|

| St. Cuthbert Gospel; source: Wikipedia (but I saw it with my own eyes and this is really it) |

The exhibition features not just biblical manuscripts, either. You can also see the only copy of Beowulf, the earliest copy of the Rule of St. Benedict, and the Great Domesday Book (as well as the Exon Domesday). A number of non-book items are of interest as well, but again, I had to rush through parts of it.

Perhaps one my unexpected favourites of the exhibition was another manuscript. I will post more on it tomorrow morning as it deserves its own discussion.

My only criticism (and I feel guilty for having any criticism at all for this excellent exhibit) is that I would have liked to see f. 1 of BL, Cotton MS Titus C XV. The other four folios are from the 6th-century purple codex N022, but f. 1 has a papyrus fragment of Gregory the Great’s Forty Homilies on the Gospels in Latin that dates right to around the time of the composition of the work itself. Robert Babcock wrote a delightful article a few years ago in which he identified the fragment and speculated (reasonably in my opinion) that it might have been one of the other books Augustine of Canterbury brought with him to Britain in 597. It would have been nice to see it next to the St. Augustine Gospels (though there is a nice image of the fragment on p. 21 of the exhibition catalogue).

It is also always a treat to see some of the treasures of the British Library that are on permanent display, like Codex Sinaiticus, the earliest complete copy of the New Testament.

In summary, drop what you’re doing and go see this amazing exhibit, but be sure to book in advance.

More to come tomorrow.

Friday, December 16, 2016

British Library and Copyright

The following caught my interest from the BL blog:

“Readers may be surprised to learn that most medieval manuscripts held at the British Library are still in copyright until 2039 under the 1988 Copyright, Designs and Patents Act (as amended). However for unpublished material created many centuries ago and in the public domain in most other countries, the British Library believes making available digital copies of this material to be very unlikely to raise any objections. As an institution whose role it is to support access to knowledge, we have therefore taken the decision to release certain digitised images technically still in copyright in the UK under the Public Domain Mark on our Catalogue of Illuminated Manuscripts website.”

I like their self-understanding as ‘an institution whose role it is to support access to knowledge’. Wouldn't it be great if all scholars thought about themselves in similar terms ...

“Readers may be surprised to learn that most medieval manuscripts held at the British Library are still in copyright until 2039 under the 1988 Copyright, Designs and Patents Act (as amended). However for unpublished material created many centuries ago and in the public domain in most other countries, the British Library believes making available digital copies of this material to be very unlikely to raise any objections. As an institution whose role it is to support access to knowledge, we have therefore taken the decision to release certain digitised images technically still in copyright in the UK under the Public Domain Mark on our Catalogue of Illuminated Manuscripts website.”

I like their self-understanding as ‘an institution whose role it is to support access to knowledge’. Wouldn't it be great if all scholars thought about themselves in similar terms ...

Friday, April 22, 2016

Micrography in Hebrew Manuscripts

The BL has just put up a new website for their digitized Hebrew manuscripts (mentioned here). You can now filter by Hebrew Bible manuscripts. There are 13 in all, seven of which are scrolls. There are some short articles on the new site as well that are worth reading. The most interesting one is on the subject of micrography. The description for the Sana’a Pentateuch (A.D. 1469) describes it this way:

And here is Jonah praying from the fish beside the text of Jonah 2 in the “Jonah Pentateuch.”

For more on micrography, see Illuminating in Micrography by Dalia-Ruth Halperin (Brill, 2013).

Micrography is an original and charming expression of Jewish art dating back to the early Middle Ages still practised today. It entails using minute Hebrew script to create geometric patterns and animate forms. Micrographic decoration can already be found in some of the Hebrew Bibles produced in the Near East in the 9th and 10th century CE. With time, this unique form of Jewish art gradually spread beyond the boundaries of the Near East, to Europe and Yemen reaching its pinnacle between the 13th and 15th centuries CE.There are some incredible designs in this micrography. Here is Psalm 119 in the Sana’a Pentateuch.

Initially, the scribes used the Masorah (body of rules on the reading, spelling and intonation of the scriptural text) to shape the micrographic outlines in Hebrew Bibles, but over time they looked for other sources, a particular favourite being the Book of Psalms.

As with Jewish manuscript illumination itself, micrographic designs tended to follow the trends in the host environment at a particular time. Thus, in Islamic lands and Spain the patterns and shapes delineated in Hebrew minuscule lettering were mainly architectural, geometric and vegetal, whereas in European countries such as France and Germany they were symbolic and figurative. Micrographic grotesques and fabulous creatures became quite popular in hand-copied books produced in Ashkenaz (Franco-German areas) in the medieval period. From the 17th century CE onwards micrography was mainly used to decorate marriage contracts, amulets, Esther scrolls and other types of Hebrew texts written by hand.

|

| BL Or 2348, f. 39r and 38v |

|

| BL Add MS 21160, f. 292r |

Wednesday, March 09, 2016

Hundreds More Digitized Hebrew Manuscripts from the British Library

|

| Add. MS 9401 f. 3r. Genesis. Dated 1588. |

Our followers and readers will be delighted to learn that over 760 Hebrew manuscripts have now been uploaded to the British Library’s Digitised Manuscripts. Generously funded by The Polonsky Foundation, the Hebrew Manuscripts Digitisation Project aims at digitising and providing free on-line access to well over 1250 Hebrew handwritten books from the Library’s collection. The project, which began in 2013 is due for completion in June 2016, when the full complement of manuscripts will be available to a global audience.I haven’t found a reliable way to filter for Old Testament manuscripts yet. If someone knows, let me know in the comments. A keyword search for “Hebrew Bible” returned 818 results but plenty of these were false hits. Just poking around though there are some beautiful Hebrew Bible manuscripts in this collection.

|

| Add MS 11657 f. 171v. Isaiah. Dated 1300-1399. |

|

| Add MS 15282 f. 75v. Exodus. Dated 1300-1324 |

|

| Add MS 9402, f. 101r. Daniel. Dated 1588. |

Thursday, October 15, 2015

Curator of Ancient and Medieval MSS at the British Library

The British Library is recruiting a Curator of Ancient and Medieval Manuscripts with a special responsibility for Classical, Biblical and Byzantine Manuscripts:

Job purpose

To develop and manage the Library’s collections of Ancient and Medieval Manuscripts, with a special responsibility for Classical, Biblical and Byzantine Manuscripts.

To interpret the collections by using innovative and traditional ways of presenting and researching the collection through online resources, engagement with academic and general users, media work, events, contribution to online resources, exhibitions and the public programme, and updating the catalogue.

To manage projects relating to Ancient and Medieval Manuscripts.

To assist in the development of selection profiles and to monitor the delivery of acquisitions against selection.

To make a personal contribution to the Library’s research and other strategies based on individual specialist knowledge of the collections and particular fields of study.Full description here.

Saturday, June 13, 2015

Conference: The Written Heritage of Mankind in Peril

The Written Heritage of Mankind in Peril: Theft, Retrieval, Sale and Restitution of rare books, maps and manuscripts

Seminar, British Library London, 26 June 2015

The theft of and illicit trafficking in rare books, maps and manuscripts looted from sovereign and other libraries and similar repositories around the world is a global problem that threatens the preservation of the recorded history of mankind. Remarkably, however, there have been few conferences devoted to the examination of the many issues that pertain to this problem.Consequently, the Art Law Commission of the UIA has teamed up with the British Library and the Institute of Art and Law in London to invite those who deal with rare books and other priceless written materials, including representatives of dealers, collectors, auction houses, national collections, law enforcement officials, security experts, attorneys and others, to present a full-day comprehensive seminar devoted to a thorough review of the many aspects of this global epidemic.

Upon the conclusion of the seminar, the various participants and attendees will be encouraged to continue the discussion throughout the following year to address the problems raised and begin to develop a comprehensive set of principles that we hope will lead to the development of solutions to prevent widespread theft and trafficking and restore stolen items to their rightful owners for the benefit of everyone. The plan would be to then hold a follow up seminar in New York in 2016 to assess progress in this area and plan future actions.

Organised by the UIA, the British Library and the Institute of Art and Law

Programme

08.30-09.00Registration, coffee

09.00-09.30

Welcome Address

Kristen Jensen, Head of Collections and Curation, British Library

Introductory Key-Note: Manuscripts as Chattels and Chattels as Manuscripts: How archives, books and manuscripts relate to cultural material at large

Professor Norman Palmer QC (Hon) CBE FSA, Barrister, Expert Adviser to the Spoliation Advisory Panel, Chair of the Treasure Valuation Committee 2001-2011

09.30-10.00

Panel I – The Extent of the Problem: Notorious Examples of Rare Book Theft

– Ivan Boserup, Former Head of Manuscripts and Rare Books, The Royal Library, CopenhagenModerator: Giuseppe Calabi, CBM&Partners, Milano

– Margaret Lane Ford, International Head of Books and Manuscripts, Christie’s, New York

– Professor Keun-Gwan Lee, Professor of Law, Seoul National University

10.40-11.00 Coffee break

11.00-12.00

Panel II – The Legal Framework for Retrieving Stolen Books: An International Case Study

– Sharon Cohen Levin, partner at WilmerHale and former Chief, Money Laundering & Asset Forfeiture Unit, U.S. Attorney's Office for the Southern District of New YorkModerator: Howard N Spiegler, Partner and Co-Chair, Art Law Group, Herrick, Feinstein LLP

– Jerker Ryden, Senior Legal Advisor, National Library of Sweden

– Jutta Freifrau von Falkenhausen, Lawyer, Berlin

12.00-12.30

Key-Note II – The Protection of Ancient Books and Manuscripts: the Turkish Experience

Professor Sibel Özel, Head of Private International Law, Marmara Üniversitesi, Istabul

12.30-13.30 Lunch break

13.30-14.30

Panel III – The Perspective of the Rare Book Trade

– Richard Aronowitz-Mercer, Head of Restitution Europe at Sotheby's, LondonModerator: Monica Dugot, International Director of Restitution, Christie’s

– Norbert Donhofer, President of International League of Antiquarian Booksellers (ILAB)

– Stephen Loewentheil, Founder and President of 19th Century Rare Book and Photograph Shop, Baltimore

14.30-15.30

Panel IV

Preventing the Theft and Trafficking of Rare Books

– Greger Bergvall, Manuscripts, Maps and Pictures Division, National Library of SwedenModerator: Kristian Jensen, Head of Collections and Curation, British Library

– Denis Bruckmann, Director of Collections, Bibliothèque Nationale de France

– Christian Recht, Senior Legal Advisor, Österreichisch Nationalbibliothek, Wien

15.30-16.00 Coffee break

16.00-17.00

Concluding Discussion: Lessons Learned and Recommendations for the Future

– Norbert Donhofer, President of ILABModerator: Gerd-Jan van den Bergh, Bergh Stoop & Sanders, Amsterdam

– Kristian Jensen, Head of Collections and Curation, British Library

– Sharon Cohen Levin, partner at WilmerHale and former Chief, Money Laundering & Asset Forfeiture Unit, U.S. Attorney's Office for the Southern District of New York

– Hetty Gleave, Partner, Hunters Solicitors, London

17.00

End of Conference – Wine reception

More info

The

Written Heritage of Mankind in Peril: Theft, Retrieval, Sale and

Restitution of rare books, maps and manuscripts - See more at:

http://www.bl.uk/events/the-written-heritage-of-mankind-in-peril#sthash.sltg4eQg.EEPn6E0l.dpuf

The

Written Heritage of Mankind in Peril: Theft, Retrieval, Sale and

Restitution of rare books, maps and manuscripts - See more at:

http://www.bl.uk/events/the-written-heritage-of-mankind-in-peril#sthash.sltg4eQg.EEPn6E0l.dpuf

Thursday, January 08, 2015

Here and there

Brice Jones has found a papyrus fragment of John for sale on ebay - see here (it all looks plausible to me). [not for sale anymore - withdrawn from the auction]

Winchester Cathedral is trying to recover illuminations stolen from the twelfth-century Winchester Bible.

The British Library has published a list of the 1220 manuscripts with new digital images in A New Giant List. Meanwhile the British Library is now allowing personal digital photography of items in the collection (applauded by Roger Pearse).

Among the top selling books and manuscripts at auction in 2014 were a number of biblical related manuscripts, including the editio princeps of the Hebrew Torah printed on vellum ($3,871,845)

Duke University is returning a tenth-century Greek manuscript to Greece (not sure what it is a manuscript of, doesn’t look like a NT, but I could be wrong).

Meanwhile some responses to the ill-informed on-line article about the Bible at “Newsweek” can be found from Mike Kruger (two parts, with comments from the author of the article); Ben Witherington; Darrell Bock (two parts); Pete Enns; Dan Wallace [up-dated here] (I’m not sure how this online “Newsweek” relates to the respected old print magazine, the ownership looks murky).

Friday, October 28, 2011

The Lindisfarne Gospels Online

Congratulations to all manuscript lovers: The Lindisfarne Gospels (BL, Cotton MS Nero D IV) have been digitized and are available online at the British Library Digitised Manuscript website.

Congratulations to all manuscript lovers: The Lindisfarne Gospels (BL, Cotton MS Nero D IV) have been digitized and are available online at the British Library Digitised Manuscript website.

Monday, September 27, 2010

British Library Digitised Manuscript Website pt 4

British Library Digitised Manuscript Website pt 3

British Library Digitised Manuscript Website pt 3

GA 687

GA 688

GA 689

GA 690

GA 691

GA 692

GA 693

GA 1268

GA 1274 pt 1

GA 1274 pt 2

GA 1956

GA 2822 + GA 2823

GA L25 ("L25a" should be changed to L25 in the description)

GA L152

GA L177 (Gregory-Aland number is omitted from contents and description)

GA L188 pt 1

GA L188 pt 2

GA L189

GA L190

GA 687

GA 688

GA 689

GA 690

GA 691

GA 692

GA 693

GA 1268

GA 1274 pt 1

GA 1274 pt 2

GA 1956

GA 2822 + GA 2823

GA L25 ("L25a" should be changed to L25 in the description)

GA L152

GA L177 (Gregory-Aland number is omitted from contents and description)

GA L188 pt 1

GA L188 pt 2

GA L189

GA L190

British Library Digitised Manuscript Website pt 1

Today the British Library launches its Digitised Manuscripts website. Read the announcements here and here ("The Medieval and Earlier Manuscripts Blog" formerly "The Digitised Manuscripts Blog").

In an earlier announcement on the blog this year, I reported that there would be 50 GNT MSS in the first phase. Now, it turns out to be 64! Hooray!

I have compiled an index of the digitized Greek New Testament MSS below. I have divided the index into several parts because of the maximum amount of labels in Blogger. The readers may thus search for a certain MS (GA ...) in the search box in the upper left corner.

GA G 011 (Codex Wolfi or Codex Harleianus)

GA R 027 (Codex Nitriensis)

GA 65

GA 72

GA 81

GA 104

GA 113 (The Gregory-Aland number is missing in the content description of the catalogue for this MS)

GA 114 (The Gregory-Aland number is missing in the content description of the catalogue for this MS)

GA 115

GA 116

GA 201

GA 202

GA 272

GA 312 pt 1

GA 312 pt 2

GA 321 (The Gregory-Aland number is missing in the content description of the catalogue for this MS; "Monologion" should be "Menologion")

GA 385

GA 478

GA 490

In an earlier announcement on the blog this year, I reported that there would be 50 GNT MSS in the first phase. Now, it turns out to be 64! Hooray!

I have compiled an index of the digitized Greek New Testament MSS below. I have divided the index into several parts because of the maximum amount of labels in Blogger. The readers may thus search for a certain MS (GA ...) in the search box in the upper left corner.

GA G 011 (Codex Wolfi or Codex Harleianus)

GA R 027 (Codex Nitriensis)

GA 65

GA 72

GA 81

GA 104

GA 113 (The Gregory-Aland number is missing in the content description of the catalogue for this MS)

GA 114 (The Gregory-Aland number is missing in the content description of the catalogue for this MS)

GA 115

GA 116

GA 201

GA 202

GA 272

GA 312 pt 1

GA 312 pt 2

GA 321 (The Gregory-Aland number is missing in the content description of the catalogue for this MS; "Monologion" should be "Menologion")

GA 385

GA 478

GA 490

Wednesday, February 24, 2010

Fifty Digitised GNT MSS and a New Blog

British Library curator Juan Garcés notified me that he has started a new blog, The Digitised Manuscripts Blog (which of course has now been added to our blogroll). The focus is to report on various issues related to the current digitisation projects at the British Library, in particularly the Greek Manuscripts Digitisation Project funded by the Stavros Niarchos Foundation.

The British Library described the project in their "Annual Reports and Accounts 2008/2009":

Digitisation of Greek manuscripts

We are very grateful to the Stavros Niarchos Foundation for making it possible for us to undertake a project to digitise 250 of our Greek manuscripts to make them fully accessible to researchers around the world through the internet. We will also create catalogue records for each item and create a website that will enable researchers to search using key words and interactive technology that will allow them to upload notes and collaborate with other researchers virtually. We aim to launch the website in summer 2010. We are continuing to fundraise to enable us to add the remaining Greek manuscripts and papyri to the site in the longer term.

In a special post yesterday, "Greek New Testament Manuscripts", Juan announced that in the first phase of that project fifty Greek New Testament manuscripts will be digitized (!): one majuscule from the 7th century; 33 minuscules from the 10th-14th centuries; and 16 lectionaries from the 11th-14th centuries. I don't know, but maybe the majuscule is Codex R (027)? [Update: confirmed by Juan Garcés in the comments.]

Joy to the world: more digitized GNT MSS.

Subscribe to:

Posts

(

Atom

)

Loading...