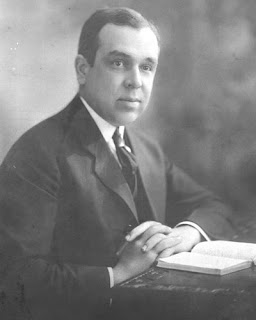

J. Gresham Machen is known for many things: starting Westminster Seminary, starting the Orthodox Presbyterian Church, writing a widely used introductory Greek grammar (one still used when I was in high school!), battling theological modernism, etc. Among his books, the most famous is Christianity and Liberalism, which is celebrating its 100th anniversary this year. It is a classic. If you’ve never read it, you should.

One thing Machen is not known for is textual criticism. Nevertheless, one will find in his major study of the virgin birth a chapter devoted especially to the textual problem of Matt 1:16. It’s a nice treatment overall. But what caught my attention was his response to the conjecture proposed by A. Merx (and others, see here) that the text initially read “Joseph begat Jesus” and this was only later emended in various ways to include Mary and her virginity. Here is Machen:In reply, it may be said, in the first place, that the method of conjectural emendation, which is here followed, can be applied only with the greatest caution to a work which has so extraordinarily rich a documentary attestation as has the Gospel according to Matthew. In the case of many classical authors, where we have only one or two late and obviously very imperfect manuscripts, an editor is often justified in rejecting the transmitted text of a passage and in substituting for it a reading which shall best account for the obviously incorrect wording of those manuscripts that happen to be extant. But in the case of the Gospels, the extant documentary attestation is so very abundant, and the various lines of transmission began to diverge at such an early time, that one has difficulty in understanding how the original text could have been so completely obliterated as to leave no trace. There may indeed be such instances, where all of our extant witnesses to the text have been corrupted; but surely they are very few. Thus although conjectural emendation cannot be excluded in principle from the textual criticism of the New Testament, it should certainly be employed there in the most sparing possible way. The employment of it in any passage should be regarded as a counsel of desperation, to be resorted to only when all ordinary methods fail. If it is possible to regard any one of the extant variants as original, that alternative should be chosen; and the critic should not undertake to reproduce by conjecture a text which has actually left no trace.

In the case of Mt. 1:16, if there is any truth in what has been said above, we are by no means reduced to such desperate expedients. It is perfectly possible to understand the reading attested by our earliest Greek manuscripts as belonging to the original text of the Gospel, and both the variants as having been produced from that reading in the course of the transmission by well-known causes of textual corruption. But if such a solution of the problem is possible, it is surely—in view of the wealth of documentary attestation— decidedly preferable. What need is there of going so far afield to solve a problem for which a satisfactory solution lies near at hand? (pp. 183-184)

I’ll just note two points of interest to me. The first is that, despite his famously staunch defense of the Westminster Confession, Machen is willing to entertain that conjecture might be needed in the rarest cases in the Gospels: “There may indeed be such instances, where all of our extant witnesses to the text have been corrupted; but surely they are very few.”

The second is that Machen’s hesitation about conjecture is based on two points not one. It is not only the “abundance” of manuscript evidence for the Gospels but also that the lines of transmission diverged so early. If this is true, then any convincing conjecture must not only explain why the original text was lost in so many manuscripts, but, more importantly, how it was lost in all the lines of transmission so early. Even still, Machen is not opposed to conjecture tout court.

P.S. It’s pronounced gress-um.

The third point raised here by Machen is that this relates especailly to Matthew. One might (at least in theory) be more open to emendations in the less well attested parts of the NT.

ReplyDeleteI shall propose a conjectural emendation to your last paragraph; it should read "...then any convincing..." rather than "...than any convincing..." Thanks for giving props to the OPC's OG; "You down with OPC?"

ReplyDeleteThe famous (infamous?) "Conjecture isn't required because we have such rich ms attestation" argument has always struck me as a kind of eating your cake and having it too.

ReplyDeleteWhen the wish to reject conjecture (not reject a specific conjecture on its merits or lack thereof, but rather simply rejecting conjectures on principle), these critics are happy to pile up all the existing manuscripts and, standing on that rich pile, boast about their conjecture negating wealth.

But then if you turn to other variants, you can routinely find those same critics rejecting many, most, or the majority of those same manuscripts for the sake of a preferred reading that is found in just a few.

Indeed, I believe I have published a list of variants where the most popular critical text today has preferred readings that have survived in just a single manuscript.

It is simply contradictory to reject on principle the idea that, in some cases, all surviving manuscripts are wrong, while at the same time being willing to accept in other cases that all but one surviving manuscripts are wrong!

Or put another way, you can't sit there boasting about how rich the ms tradition is if you are also already on record saying that in some cases you think they are almost all wrong.

Conservative evangelicals need to be honest - with themselves - about the real richness of the surviving manuscripts.

Yes, we have an awful lot of them, and yes, quite often - most the time even - the most likely original reading is preserved in many of those manuscripts.

But we also know that in a good number of cases, most of those manuscripts are not so rich at all, and in some cases almost everyone of them appears to be wrong. And if they weren't so concerned with propping up an artificially inflated view of the scriptures - one that's higher than the scriptures even claim for itself - they would also be able to see that there are indeed some cases where it's not just almost all the surviving manuscripts which appear to be wrong, but in fact all of them appear to be wrong. In such cases, a true and responsible stewart of the scriptures will use every tool God has given them to restore the text - including the tool of conjecture.