Last week I published a list of historic English Bibles to complement Pete Head’s list. Today, I want to illustrate one way to use it. In this case, I am interested in how the earliest printed English Bibles handle the famous variant in 1 John 5:7–8. (My interest was originally sparked by Hixson’s post.)

One thing you learn from studying these Bibles is that their translators often used whatever other major editions or translations they could to produce their Bibles. As one example, Coverdale used five “sundry translations” for his 1535 Bible and these probably included Luther, the Zurich Bible, Pagninus’s Latin, the Vulgate, and Erasmus (per David Norton). It’s worth looking at how these early English Bibles navigated the lack of uniformity on the Comma among their sources. So, here is a whistle-stop tour of the main English Bibles up to the King James.

1. Tyndale (1526)

2. Tyndale (1534)

3. Coverdale (1535)

4. Matthew Bible (1537)

5. Great Bible (1539) - paywalled

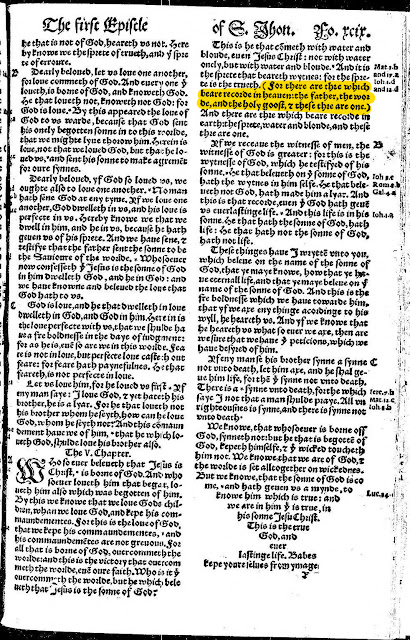

This Bible was a revision of the Matthew Bible done by Miles Coverdale. For our purposes, it needs to be noted that it includes words and sentences from the Vulgate set in smaller type and brackets to “satisfy and content those that herebeforetime hath missed such sentences in the bible and New Testaments before set forth.” The Comma is so marked, as a reading from the Vulgate not the Greek.

6. Taverner (1539)

Along with the Rheims NT below, Taverner is the only English Bible in this period I know of with a note about the textual issue with the Comma. From a cleaner scan on ProQuest, the note says, “This that is printed in other characters after the judgment of Erasmus in his annotations be not the words of John, the writer of this Epistle, but came to be put in, of some other.” (Thanks to Tim Berg for help in reading it.) Despite the note saying it doesn’t belong, it’s still included. Perhaps there’s an analogy here to scribes?

7. Geneva (1557, 1560)

There is no note on the textual issue in these two Bibles famous for their copious notes. To be fair, I haven’t seen any notes in these editions that get in weeds on a textual variant. (The 1557 is available online online in a later reprint.)

8. Bishops’ Bible (1568, 1602)

A revision of the Great Bible. The 1602 edition was the base text for the KJV.

9. Rheims NT (1582)

A translation of the Vulgate, it’s not surprising to find the Comma without any demarcation in the Rheims NT. The accompanying annotation reads, in updated spelling:

7. Three which give testimony. ) An express place for the distinction of three Persons, and the unity of nature and essence in the B.[lessed] Trinity; against the Arians and other like Heretics, who have in diverse Ages found themselves so pressed with these plain Scriptures, that they have (as it is thought) altered and corrupted the text both in Greek and Latin many ways: even as the Protestants handle those texts that make against them. But because we are not now troubled with Arianism so much as with Calvinism, we need not stand upon the variety of reading or exposition of this passage. See S. Hierom. in his epistle put before the 7. Canonical or Catholic Epistles.

One minor point here. When the Rheims says “we need not stand” on the variant or its meaning, the phrase “to stand” at the time often meant “to pause” or “linger on” (per OED). It does not mean “to take a position on” or “defend something” like it does today. The Rheims translators are not saying the decision is of little consequence; they’re just saying they don’t need to spend any more time on it since their current trouble is with Calvinists (who affirm the Trinity) not Arians (who don’t).

Great collection of images. It would be relevant to show what all these editions do at 1 John 2:23, where even the KJV marks uncertainty about the words.

ReplyDeleteAssume (1) that the disputed words are to be omitted; and that (2) a masculine plural participle may govern three neuter singular nouns; then (3) What is the exact/proper translation of the final phrase, “και ‘οι τρειc ειc το ‘εν ειcι”; and (4) exactly what is the referent of “το”?

ReplyDeleteNo comments on translation of the clause and on the referent of το?

DeleteAre you sure the Coverdale quote is from his 1535 text or the Matthew's? I cannot find that in any of the prefaces except something similar in Coverdale's 1538 diglot, which should not be interpreted as the same for his other texts (this one being unique).

ReplyDeleteChristopher, this is what’s in my electronic edition, which has 1535 on the title page. Not sure what you mean by finding it in the prefaces.

DeleteAre you sure the Coverdale quote is from his Bible? I cannot find it in the preface of the Matthew or the Coverdale Bible. A similar statement is in the 1538 Coverdale NT diglot, but I don't think that should be carried over to his other translation work since it was a unique project.

ReplyDelete