Tuesday, August 29, 2006

An online feast

Monday, August 28, 2006

Farewell to the Prologue of John

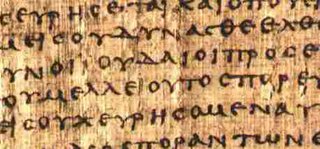

John 1:1-18 is now nearly universally identified as a sense unit of the text of the Fourth Gospel. Frequently the term 'Prologue' is applied to these verses. This paper examines the way the opening of John's Gospel has been divided through history, considering the evidence of manuscripts, early versions, church fathers, liturgy, printed editions and commentators. It is observed that the earliest division (attested in P66 and P75 and probably deriving from the archetype of the textual tradition) marks a division after 1:5, but no similar division after 1:18. At a slightly later stage significant breaks are found in witnesses after 1:14 and 1:17 (1:1-17 frequently forming a lection). Even with the advent of printing, 1:1-14 and 1:1-17 are initially marked as units. As increasingly 1:1-18 is regarded as the basic unit, the break after 1:5 becomes less prominent and a break after 1:13 tends to take over from the break after 1:14 since 1:14 is no longer a final climax. The earlier ways of dividing the text still present significant advantages in analysing the opening section of John's Gospel. The near-universal adoption of 1:1-18 as the basic unit has allowed various speculative theories as to the origin of these verses to arise. Proponents of these theories usually ignore the hypothetical nature of the textual division which is foundational to their proposals.

Where to do a PhD

I describe my own view of the British situtation (here) and Bart Ehrman explains for us the ethos at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, initially responding to the suggestion of Malcolm Robertson that “I would not recommend any state/secular university esp and particularly the University of Chicago or the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, North Carolina USA.”

The whole correspondence is worth perusing, but I think that Ehrman’s exchange with Tommy Wasserman perhaps highlights an area where approaches to TC are diverging most significantly. The messages are: Ehrman, Wasserman, Ehrman’s reponse.

The messages particularly raise the question as to what are the most important skills and competencies for a textual critic to have.

In addition to the issues raised in that thread I want to raise a few more questions that are relevant to choice of a venue for a PhD:

(1) To what extent is it important to study in a confessional environment? The ideal learning environment may vary from person to person and may vary through the stages of life. All education models are imperfect and we are often looking for the least bad one. Confessional environments can sometimes create people who want to escape—they think the grass is greener elsewhere. If you’ve been trained in a non-confessional environment you are aware that it often isn’t.

(2) To what extent is the supervisor the person who should be helping an evangelical student think through matters in an evangelical way? In some settings it might be that an non/anti-evangelical supervisor alongside strong personal intellectual support from a local evangelical thinker might be a better route than simply to rely on an evangelical supervisor to get it right for you.

(3) People need to assess the relative importance of the institution and the supervisor since supervisors may move (or die or get ill or even get promoted into administration). If you go to an institution just for the supervisor, what would your experience be like if that supervisor were no longer available? If they only have one specialist in NT or OT then you may be in a difficult situation.

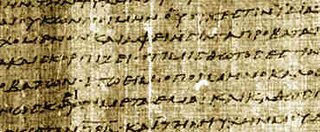

Manuscript pictures link

Saturday, August 26, 2006

Why are the kephalaia of John longer?

The Gospels have the following number of kephalaia:

Matthew: 68

Mark: 48

Luke: 83

John: 18

Why are there fewer kephalaia in John? Is there any evidence that they derive from a different source from those on the synoptics? Could early popularity of John have meant that it gained a system of chapters earlier?

Friday, August 25, 2006

Center for the Preservation of Ancient Religious Texts

There is a lot of activity at the center. They are collecting and digitizing a large number of Eastern Christian manuscripts and they have published electronic facsimiles of thirty-three Syriac manuscripts from the collection of the Vatican Library. At the Syriac section, David Taylor (formerly Birmingham) is involved in a project that will make essential Syriac texts and tools available on-line. The works to be included are listed in a bibliography: http://cpart.byu.edu/ECRL/biblio.php

Tuesday, August 22, 2006

John of Placenta

Amy Anderson joins blog

One of the things that J. Neville Birdsall wrote before his death was a review of Amy's monograph in JTS 57 (2006) pp. 235-46. He was not always lavish in his praise of the work of others but on this occasion wrote: ‘I have little but applause for what it presents’.

Amy is featured as number 6 in round 3 of our identity quiz.

Sunday, August 20, 2006

Rodgers reviews Misquoting Jesus

Saturday, August 19, 2006

The Unity of Luke-Acts and Second Century Gospel Collections

p45 p53 05

(We could include 01, A, B, and C but these usually comprise the whole NT [i.e. eacpr], so the co-existence of Luke and Acts together there is not significant either way.)

In fact, p53 contains Mt. 26.29-40 and Acts 9.33-10.1. (How about a case for the narrative unity of Matthew-Acts based on this manuscript?)

What do the NT manuscripts tell us about the unity of Luke-Acts? If Luke and Acts were rarely found together in the one manuscript/codex, does that provide further evidence that Luke and Acts were not read as a narative unity by second and third century Christians? Does the dislocation of Luke and Acts assail the coveted assumption of literary critics that Luke-Acts was written as a narrative-unity and read that way by its first-century readers? Or, do we have a situation more analagous to that of Josephus' Antiquities and Against Apion, where the preface to Apion (like that of Acts) refers to a previous work but without actually being an extension of it? After all, Luke ends his Gospel with an ascension narrative, while Acts commences his historiography of Christian Origins with an ascension 40 days after the resurrection. Is the assumption that Luke and Acts were originally one literary unitk, but were separated early in the second century, a valid assumption?

Whether TC can shed any light on this topic is one question. What the significance might be to the unity of Luke-Acts is, however, another.

Thursday, August 17, 2006

Two new reviews of Ehrman

The other is an insightful extended review (387-91, nearly five dense pages) by Michael J. Kruger (of the Reformed Theological Seminary, Charlotte, NC). His treatment includes some thoughtful comments re the theological issues raised by Ehrman's book, and a brief analysis of Ehrman's own theological assumptions that shape how he deals with the issue of inspiration (Kruger concludes that "Ehrman is working with his own self-appointed definition of inspiration which sets up an arbitrary … standard that could never be met. Does inspiration really require that once the books of the Bible were written that God would miraculously guarantee that no one would ever write it down incorrectly?"). To cite just one of his major observations, Kruger notes that "Ehrman wants to be able to have his text-critical cake and eat it, too. One (sic!) the one hand, he needs to argue that text-critical methodologies are reliable and can show you what was original and what was not, otherwise he would not be able to demonstrate that changes have been made for theological reasons … Yet, on the other hand, he wants the 'original' text of the NT to remain inaccessible and obscure, forcing him to argue that text-critical methodologies cannot really produce any certain conclusions. Which is it?"

Apparently (though I would be glad to be corrected on this point) currents issues of JETS are not available on line, but for those interested, these two reviews make a trip to the library worth the effort.

Plato and Mark 16:8

Earlier in 2006, Nicholas Denyer published a short article entitled "Mark 16:8 and Plato, Protagoras 328d." in Tyndale Bulletin 57 (2006), 149-150 (previously mentioned and discussed here here)

- Summary:

What we have of the Gospel of Mark comes to an abrupt halt at 16:8 with the words KAI OUDENI OUDEN EIPAN EFOBOUNTO GAR (‘And they said nothing to anyone, for they were afraid’). Such a cliff-hanger was felt intolerable by some ancients, who composed and transmitted to us various passages that bring the Gospel to a more satisfying close. Plato, Protagoras 328d provides further confirmation that EFOBOUNTO GAR (‘for they were afraid’) is an astonishingly abrupt end. But it also provides proof that so astonishingly abrupt an end could well be deliberate.

The relevant section of Plato's Protagoras (in Jowett's English translation anyway):

- Such is my Apologue, Socrates, and such is the argument by which I endeavour to show that virtue may be taught, and that this is the opinion of the Athenians. And I have also attempted to show that you are not to wonder at good fathers having bad sons, or at good sons having bad fathers, of which the sons of Polycleitus afford an example, who are the companions of our friends here, Paralus and Xanthippus, but are nothing in comparison with their father; and this is true of the sons of many other artists. As yet I ought not to say the same of Paralus and Xanthippus themselves, for they are young and there is still hope of them (ed: ETI GAR EN AUTOIS EISIN ELPIDES, NEOI GAR).

- Protagoras ended, and in my ear So charming left his voice, that I the while Thought him still speaking; still stood fixed to hear.

- At length, when the truth dawned upon me, that he had really finished, not without difficulty I began to collect myself, and looking at Hippocrates, I said to him: O son of Apollodorus, how deeply grateful I am to you for having brought me hither; I would not have missed the speech of Protagoras for a great deal. For I used to imagine that no human care could make men good; but I know better now. Yet I have still one very small difficulty which I am sure that Protagoras will easily explain, as he has already explained so much. If a man were to go and consult Pericles or any of our great speakers about these matters, he might perhaps hear as fine a discourse; but then when one has a question to ask of any of them, like books, they can neither answer nor ask; and if any one challenges the least particular of their speech, they go ringing on in a long harangue, like brazen pots, which when they are struck continue to sound unless some one puts his hand upon them; whereas our friend Protagoras can not only make a good speech, as he has already shown, but when he is asked a question he can answer briefly; and when he asks he will wait and hear the answer; and this is a very rare gift.

James E. Snapp, Jr. writes:

The material in Denyer's article shows that Protagoras 328c and Protagoras 328d do not support the idea that Mark intentionally ended his Gospel-account with "gar."

Protogoras 328c constitutes the ending of a speech; it is not the end of a book. The conclusion of the speech is essentially a comment made by the speaker to anticipate an objection to the speaker's main idea. Plato's text goes on (in Protagoras 328d) to present Socrates' reaction to the speech which Protagoras just delivered: Socrates continues to stare at Protagoras, expecting him to say more. But Socrates' expectation is not necessarily due to the presence of "gar," and it is easy to picture Socrates responding to the speech in exactly the same way if Protagoras' final statement had been expressed in other words.

Denyer posits that Protagoras 328d "provides proof that so astonishingly abrupt an end could well be deliberate." However, it is one thing to deliberately end a topical speech with the equivalent of, "Some may say that those boys are incorrigible; they are young, however;" it is another thing entirely to deliberately end a narrative with "gar" the way it is used in Mark 16:8. Protagoras' closing comment wrapped up a loose end. The abrupt ending of Mark creates a loose end.

Wednesday, August 16, 2006

L.M. McDonald on Ancient Manuscripts and the Formation of the NT

A. The New Testaments of the early church are very different from the one in use today. The differences include the actual number of the NT writings contained in most collections (e.g. rarely the whole NT) and the existence of non-canonical documents (e.g. Sherpherd of Hermas, 3 Corinthians, Acts of Paul, etc) in these collections. Some Christians may have adopted something like a "canon within the canon" by teaching and preaching from books that had more relevance to their communities.

B. From the very beginning persons within the early church were aware that they did not have access to the "originals" and were also aware of variations within the manuscript tradition.

C. Those churches that had their Scriptures in a translation generally had fewer books available than those who had their Scriptures in Greek. The churches resisted any proclivity to ascribe inspiration and authority to any one particular translation.

D. Since the church's theology was established without original manuscripts and without a full NT canon, how significant is it that early churches did not have all the Scriptures that the church has today?

E. No major teaching of the church hinges on a variant in a mansucript and most intentional changes moved towards orthodoxy, not heresy.

F. How did the lack of original texts and a complete Bible (as we know it) impact the life and theology of the church?

I think that McDonald raises some good questions here.

Whitlark and Parsons on Luke 23.34a

Re: Jason A. Whitlark & Mikael C. Parsons, ‘The “Seven” Last Words: A Numerical Motivation for the Insertion of Luke 23.34a’ New Testament Studies 52 (2006), 188-204.

In this article the authors argue that the saying ‘Father forgive them for they know not what they do’ (Luke 23.34a) was most likely not original to Luke; but was added, as the four Gospels were collected together, because of ‘numerical motivation’ - a desire that Jesus would speak seven rather than six last words from the cross.

They argue that the shorter reading (lacking the phrase) is attested in early representatives of the Alexandrian, Western and Byzantine text-types which also exhibit geographical diversity (there is a lack of detail in this argument, but it is not the original part of the study). The longer reading has early attestation ‘almost exclusively’ within Western witnesses, and only later (post 4th Cent) in other types of witness. This suggests an originally short text, which ambiguous internal evidence cannot over-rule: ‘the logion is a secondary reading added to the text in the late second century’ (p. 194).

The new argument developed here is that the foundational motivation for the secondary inclusion of this logion was ‘a numerically symbolic one’. The basic idea being that (following Stanton and Hengel) ‘by the mid-second century, the mainstream of Christendom was working with a four-gospel collection’ (p. 195). Once collected together it would have been apparent that Jesus spoke six words from the cross, but the number six carried a negative connotation in early Christianity (e.g. Rev 13.18; John 2.6; 19.14; Luke 23.44), while seven was clearly positive and significant (various evidence cited on p. 198-201). Thus:

- ‘When the four Gospels were formed into a single collection early on and the narratives read together, the problem of six sayings from the cross emerged and created the “need” for a seventh saying.’ (p. 201)

The authors think that on this view the seventh word ‘gives a gratifying sense of completion’ when Jesus says ‘It is finished’ in John 19.30. But if Luke 23.34a was added first in the Western textual tradition then the order of the gospels would most likely have been Matt - John - Luke - Mark (as it is in Western witnesses)!

Am I being too harsh? Should ‘scribal numerology’ be added to our list of scribal habits

Up-date: the authors respond (ever so lightly edited):

We were given notice that our article was being discussed in this forum; we hope you don’t mind us joining the fray! It is, of course, all authors’ hope that their work will be read and discussed in the marketplace of ideas, and we are grateful to Peter Head for bringing our article to the attention of this group. It is not clear to us, however, that any of the other commentators have actually read the piece, and this is lamentable given the fact that the essay is relatively accessible for NTS subscribers here.

Furthermore, we think Dr Head has given a truncated and weakened version of our argument; this in and of itself is not unusual. In fact, it’s the way most of us score academic points, but such a truncated summary leads naturally, if not inevitably, to the judgment (by someone else) that what we have produced is “piffle” (we don’t know whether or not to be offended by this; we hear a LOT of words in Texas don’t understand, but piffle is not one of them!). As we understand it, Dr Head’s objections to the argument consist in

- not accepting an early date for the four-fold collection of the gospels;

- finding it implausible that a scribe would be ‘numerically motivated’ to add a seventh saying to the collected cross sayings.

BEGIN QUOTATION

Tatian’s Diatessaron is our earliest extant witness (c. 170) to the words of Jesus from the cross collected together in a single narrative, and it also attests to the secondary nature of Luke 23.34a.[1] Tatian’s order of sayings reads: (1) Luke 23.43, (2) John 19.26-27, (3) Mark 15.34/Matt 27.46, (4) John 19.28, (5) John 19.30a, (6) Luke 23.34a, and (7) Luke 23.46a. What is notable about Tatian’s order (at least according to the Arabic witness) is that the sayings from John and the two undisputed sayings in Luke maintain their original canonical narrative order. Only Luke 23.34a is out of place:[2]

Luke John

23.43 (1) 19.26-27 (2)

23.34a (6) 19.28 (4)

23.46a (7) 19.30a (5)

Important witnesses to Diatessaronic readings, the Syriac versions c and s, also attest to the secondary nature of the logion in the Third Gospel. These manuscripts are believed to be from the fourth-fifth century. The texts, however, are thought to go back to the early second and third century. Syrs is thought to be older than syrc—even pre-Tatian. Interestingly, syrs does not contain the logion, ‘Father forgive them’ while, on the other hand, syrc, which is post-Tatian, has the logion (‘Father forgive them’) in its version of Luke.[3] In these two Syriac versions we see the transition from the logion’s absence in the text of Luke in the early second century to its appearance in the text of Luke in the early third century. This is the same time frame suggested below for the logion’s addition to the Third Gospel.

Ephraim’s fourth-century commentary on the Diatessaron has some correspondence to the Arabic witness.[4] Chapters 20-21 are an account of the passion narrative and death of Jesus. Ephraim cites all but the Johannine sayings in this account. He cites Luke 23.43 (20.24-25) first, then Mark 15.34/Matt 27.46 (20.30), Luke 23.46a (21.1) and only at the end in corollary discussions does he quote Luke 23.34a (21.3, 8). What is the significance of these observations? These witnesses attest to the fact that early on the logion, ‘Father, forgive them,’ was not fixed in the text of Third Gospel but was a ‘floating tradition.’ Either it was located in various places in the text or omitted altogether. Such floating traditions are sure indicators that the traditions we are dealing with are secondary to the earliest form of the text.[5]

In addition, what do we find concerning the order of sayings in later Diatessaronic witnesses? The Middle-English Pepysian gospel harmony has the following order: (1) Luke 23.34a, (2) John 19.26-27, (3) Luke 23.43, (4) Mark 15.34/Matt 27:46, (5) John 19:28, (6) John 19.30, and (7) Luke 23.46a. In the ninth-century Saxon Heliand, songs 66-67 share an almost identical order minus John 19.30 (unless the end of song 67 is an allusion to this saying).[6] The Persian Diatessaron records the sayings from the cross in the following order: Luke 23.34a, John 19.26-27, John 19.28, John 19.30, Luke 23.43, Mark 15.34/Matt 27.46, Luke 23.46a.[7] Also, the common modern homiletical order of the sayings is (1) Luke 23.34a, (2) Luke 23.43, (3) John 19.26-27, (4) Mark 15.34/Matt 27:46, (5) John 19:28, (6) John 19.30, and (7) Luke 23.46a.[8]

In all these later examples, after the logion had been fixed in the canonical text of Luke, the logion, ‘Father forgive them’, is the first logion and maintains the canonical narrative integrity of the sayings of Jesus from the cross in the Gospel of Luke. In fact, the preponderance for starting with Luke 23:34a in the later traditional homiletical order of the seven sayings as well as in other subsequent gospel harmonies makes sense after this logion finds its place in the Gospel of Luke. Putting it first maintains the canonical integrity of Luke’s order of sayings and maintains the logical chronological sequence when all the canonical Gospels’ cruicifixion accounts are read together since this saying is immediately given after the Roman soldiers nail Jesus to the cross.

All this suggests that at the time Tatian wrote his Distessaron (ca. 170 c.e.), this logion had not yet secured its place in the text of Luke. This logion was most likely added to a gospel harmony or harmonized collection of sayings of Jesus on the cross before it was added to the text of Luke.

END QUOTATION

With regard to point #2, namely that we “certainly haven’t shown any evidence that a scribe is likely to count sayings like this”, we would beg to differ. In a later comment, Dr Head admits that we have some evidence for scribal interest in “seven.” In addition to the use of seven as a structural principle at the compositional level (see also François Bovon’s SNTS presidential address in NTS [‘Names and Numbers in Early Christianity’, NTS 47 (2001) 267-88.), we mentioned also the following (200-201):

BEGIN QUOTATION

These previous examples indicate the influence of seven at the compositional level of the New Testament writings and traditions. ‘Seven’ also influenced the post-publication editorial collection of some New Testament texts as well as some non-canonical collections of early Christian texts. The original collection of the letters of Ignatius, written as he was traveling to Rome to be martyred, is a collection of seven letters.[9] When the catholic letters are finally collected together there are seven (1 and 2 Peter; 1, 2, and 3 John; James; Jude). More important to our discussion are the various collections of Paul’s letters by the end of the first century. Likely the oldest collection of Paul’s letters was the seven churches edition when letters to the same communities were counted together (Romans, Corinthians, Galatians, Ephesians, Philippians, Colossians, Thessalonians).[10] The significance of a collection of Paul’s letters addressed to seven churches was not lost upon the early church. The Muratorian fragment contains this interesting statement:

- Since the blessed apostle Paul himself, following the order of his predecessor John, but not naming him, writes to seven churches in the following order: first to the Corinthians, second to the Ephesians, . . . Philippians, . . . Colossians, . . .Galatians, . . . Romans. But although [the message] is repeated to the Corinthians and Thessalonians by way of reproof, yet one church is recognized as diffused throughout the world (emphasis added).[11]

END QUOTATION

This argument tracks well with Mike Holmes’ comment in the blog of the Muratorian fragment and the need for evidence from the second century.

At any rate, thanks again to Peter for bringing attention to our article. We hope it will prompt more discussion (and perhaps even a few more actually to read). We look forward (we think!) to the continuing exchange.

Cheers,

Mikeal Parsons and Jason Whitlark

Tuesday, August 15, 2006

Back to life—TC: A Journal of Biblical Textual Criticism

Wayne C. Kannaday, "Are Your Intentions Honorable?": Apologetic Interests and the Scribal Revision of Jesus in the Canonical Gospels

- Abstract: Scribes working with New Testament MSS sometimes left "fingerprints" on the text that betray their particular theological interests, many of which were apologetic in nature.

Josep Rius-Camps and Jenny Read-Heimerdinger, The Message of Acts in Codex Bezae: A Comparison with the Alexandrian Tradition. Vol. 1: Acts 1.1-5.42: Jerusalem. (Tobias Nicklas, reviewer)

Good luck to the restarted journal!

Textual Criticism: Theological and Social Tendencies?"

The Fifth Birmingham Colloquium on the Textual Criticism of the New Testament will be held from 16-19 April 2007 at Woodbrooke Quaker Study Centre, Selly Oak, Birmingham.

The Theme is "Textual Criticism: Theological and Social Tendencies?"

[PMH: Interestingly the web-site advertises the title as "Textual Variation: Theological and Social Tendencies?" I wonder if this variant reading arises from any theological or social tendency?]

Proposals are invited for papers of 30 or 45 minutes.

Suggestions for workshops, presenting work in process, are also welcome.

[PMH: Here is the call for papers with email address for proposals]

Get the date in your diaries and get those proposals in now. A very congenial conference.

Griffin on Digital Imaging

Griffin (from the Center for the Preservation of Ancient Religious Texts CPART at Brigham Young University) offers a helpful overview and survey of digital imaging (an issue that we have mentioned several times in this blog), alongside a running comparison with microfilm imaging (which shows that digital imaging is not by any means always better than microfilming, especially for archiving the material), and brief reflections on/mentions of current projects including Sinaiticus, the Freer manuscripts, and Herculaneum papyri. He concludes:

- "Looking toward the future, we may anticipate a day when many textual scholars will have instant access to high-quality images of the most important manuscripts of their fields. That is, in fact, a reasonable expectation, and not merely a fond wish." (p. 70)

Friday, August 11, 2006

Plenty of Textual Criticism at SBL

Wednesday, August 09, 2006

Metzger´s commentary revised?

[work announced on Wieland Willker´s list]

Monday, August 07, 2006

Colour-coded Manuscript

It is less well-known that at least one Gospel manuscript had attempted a colour-coding of its presentation. This is Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Codex Grec 54 (bilingual diglot; 13th Cent. = Gregory/Aland minuscule 16), dubbed by Gregory 'the rainbow manuscript' (Canon and Text, 372). It uses a range of different colour to indicate different speakers:

- bright red ink: simple narrative text

- darker red/crimson ink: the genealogy of Christ, the words of angels, the words of Jesus

- blue ink: OT passages, words of disciples, Zachariah, Mary, Elizabeth, Simeon, John the Baptist

- dark brown ink: words of Pharisees, people from crowd, Judas Iscariot, the devil, shepherds, scribes, the Centurion

For full discussion of the manuscript and its production see Kathleen Maxwell, 'Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Codex Grec 54: Modus Operandi of Scribes and Artists in a Palaiologan Gospel Book' in Dumbarton Oaks Papers, 54(2000) 117-138; esp. p. 123 for the four colours and speakers (pdf here). It is a particularly interesting manuscript because it was unfinished and therefore reveals more of the scribes workings than is usually seen.

Unfortunately I have not been able to find colour pictures (black and white plates published with Maxwell's article are here).Maxwell doesn't discuss the hermeneutical impact of such a colour-coding scheme on readers/viewers.

Biblical Manuscripts on Display in the British Library

Warmly recommended.

Thursday, August 03, 2006

Jongkind on Lilies of the Field

D. Jongkind, '"The Lilies of the Field" Reconsidered: Codex Sinaiticus and the Gospel of Thomas', NovT XLVIII (2006), 209-216.

Wednesday, August 02, 2006

X-ray fluorescence

Bog of the Month?

Tuesday, August 01, 2006

TC Alternate List

The blurb is as follows:

"This is an alternate Textual Criticism group for people with a wider set of views and more diverse backgrounds than just 'university scholarship'.

This group allows discussion of other related topics, like theology and doctrinal issues, as well as humour and politics.

Anonymity is allowed. Credentials are not required or desired. All participants should and will be judged based upon the content of their posts only. Please stick to one name only."

Whose Word Is It? and Misquoting Jesus Compared

Continuum, publishers of Whose Word Is It?, have also brought out the various images rather more crisply.

The pagination is very occasionally different in the two editions, but overwhelmingly pages are typographically identical.

In general typos have been faithfully transmitted from one edition to the other:

- scriptuo continua (pp. 48, 90)

- Desiderus Erasmus (p. 70)

- periblepsis (p. 91 bis)

- v. 27 [for v. 30] (p. 192)

Though ‘the Timothy LeHaye and Philip Jenkins series Left Behind‘ has now been corrected to ‘the Timothy LaHaye and Jerry Jenkins series Left Behind‘ (p. 13).