Saturday, September 30, 2006

More on "Apparatus Criticism"

In an appendix to his volume on the New Testament Greek Manuscripts on 2 Corinthians, Swanson refers to problems in the apparatus of Tischendorf (169), UBS4 (51), Nestle-Aland27 (148), and those in Kenyon's transcription of the Chester Beatty Papyri, all in relation to 2 Corinthians. A large number of these problems/errors occur in areas where the editors of UBS4 and NA27 try to fill in blanks in the lacunae in the manuscripts. It is this "filling-in" which Swanson seeks to question. Swanson also claims to have identified 129 misleading and incorect variant readings in Kurt Aland's Arbeiten zur Neutestamentlichen Textforschung. Text und Textwert der Griechischen Handschriften des Neuen Testaments. II. Die Paulinischen Brief (Walter de Gruyter: Berlin/New York, 1991).

In a comment about Kearfott's thesis on Washingtonianus, Peter Head makes a good points that one should take into account the aims of the apparatus in certain editions (e.g. deliberately not comprehensive and attempting to simplify the evidence at points). I would add that speculating about lacunae is fine, as long as you tell people that you're speculating. This raises the question of whether Kearfott and Swanson have misread the strategy and aims of the apparatus in NA27 and are simply being pedantic, or whether the apparatus that we are accustomed to using really do need to be double checked, more detailed, or overhauled.

One thing I do like about Swanson's volume is that he chooses Vaticanus as his base text rather than an eclectic text and he (rightly) questions the assumption that "an eclectic text is superior to an actual manuscript text that had been scripture for an early Christian community" (p. xvi).

Edition of Protevangelium of James

Friday, September 29, 2006

TC articles in the latest issue of JTS

C. M. Tuckett

Nomina Sacra in Codex E

D. C. Parker

Review Article: The Text of the New Testament: Its Transmission, Corruption, and Restoration. By BRUCE M. METZGER and BART D. EHRMAN. Fourth Edition. Pp. xvi + 366. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005

Tregelles Quote Quiz

"The fact is that Tregelles’s theological intolerance makes the truthfulness of his Greek text all the more striking."

Thursday, September 28, 2006

Original Text, Canon, Editiorial Process

As is well known, there are editiorial notes in the Tora "e.g., "... up to this day". Even taking the most conservative view of the Tora minus one, that Moses wrote the "whole" Tora [the absolute most conservative would be that Moses wrote the Tora and prophesied the future annotations, too] we still have the question of "editions". Our Hebrew Bible editions include the annotations. Is the 'annotated' edition the "original"?

At the other end of the spectrum we have Jeremiah. We appear to have multiple editions (I don't think that textual criticism alone can adequately deal with this.)

To this we could inject a theological starting point, e.g., the words of Yeshua recorded acc. to Mt 5:18 'not one iota or projection will pass from the law' and John 10:35 'scripture cannot be broken'.

Was Yeshua claiming that the 'first edition' was recoverable in the first century down to the exact spelling? Or are we asking the wrong questions? Was he accepting a "canonical text"?

These are rather typical questions of boundaries. At what point does the text become, or stop becoming, "the original text". It may not be too different from defining 'person', or 'life'. At what point? Today most evangelicals tend toward 'conception' as the neat, logical way to define 'become alive'. Something similar is taking place with this 'inspired original' idea. It cannot be easily defined or linked to any one specific hard copy of a text. It is the 'inspired code', the message '(to be) written down', not the ink on any one parchment. Like DNA, it is the code, not any one set of molecules.

If multiple editions were not enough, the Hebrew Bible also raises the question of potential multiple readings. There are points of ambiguity in the unvocalized Hebrew text. Yes, it is true that someone fluently conversant with the language can read most of the text unambiguously. But there remain points of ambiguity. [A related, earlier blog on the Hebrew Bible is: Signficance of Hebrew Pointing]

Writing systems are not the issue here and the unvocalized Hebrew Bible can still include an authorical intention, an 'inspired code' that is only partially recorded in pre-Masoretic periods. That was part of the purpose of having readers in the synagogue with ten 'critics'. The received code remained true. (Ultimately, this was recorded in our MT.) The MT is part of what may be called 'the oral law'. That is part of the reason that the oral law and written law are entwined within Judaism. You can't have one without the other. (cf. Mt 23:3 'do and keep whatever they tell you'.)

Anyway, I think that the way to approach these questions is through bifurication. To posit an 'idealistic' viewpoint and a 'practical' viewpoint. Idealistically, we can posit that there was an official inspired edition, a.k.a. the autograph, the inspired code. [Hopefully, that wouldn't be a fourth revised draft that already included a misspelling or scribal elipsis. Though one could accomate this with an inspiration theory that stretches through various editions.] Practically, we can accept a canonical text that God has given us to orient our lives around.

The NT and OT are inverted here.

The NT 'idealistic' text is almost visable through our rich textual data. (It is visable but there are points of doubt on details and the question of multiple editions is not addressed and unrecoverable.) But the canonical text is less clear. Is it NA27, 28, WH, or the best Byzantine edition? (The Orthodox churches would choose the last item.) Does the canonical text change? Maybe. And as previous discussions on this blog attest, there is a temptation when only looking at the NT to equate the canonical text with the idealistic text.

For the OT, most text critics frankly admit that any 'original' is unrecoverable and that there were probably layers of editions that we cannot penetrate. The 'idealistic' can only be dreamed, though in faith we assume that the practical text sufficiently relates to this idealistic text. Ironically, the canonical text may be clearer than a NT "canonical text". The MT, if accepted as canoncial, is very very 'tight'. (More problems develop if either the LXX or other composites of Hebrew tradition are chosen for the canonical text.)

Where do evangelicals stand? Does the acceptance of a "canonical text", warts and all, help or hinder? (Maybe 'blog' format isn't suitable for this. Pls shorten or redirect as others wish.)

Kearfott on Washingtonianus

I googled a synopsis on-line:

"This dissertation documents 1520 discrepancies that occur in the critical apparatus of the 27th edition of the Nestle-Aland Novum Testamentum Graece with respect to the biblical manuscript Codex Washingtonianus and calls for the development of the discipline known as apparatus criticism, by which the manuscript evidence contained in the Nestle-Aland critical apparatus would be rendered thorough and accurate.

- Chapter 1 introduces the discipline of apparatus criticism and establishes its position as a logically prior sub-discipline of textual criticism, as well as its importance to New Testament scholarship in general.

- Chapter 2 provides background on the manuscript which is serving as the case study for apparatus criticism, Codex Washingtonianus. Both the history of the manuscript and the significance of the manuscript are examined.

- Chapter 3 is the bulk of the dissertation and offers the strongest proof of the need for apparatus criticism by documenting the 1520 discrepancies, which occur both explicitly and implicitly in currently recorded variation units as well as where no variation unit currently exists. Correction of these variants is also provided.

- Chapter 4 explores the contributions to be made toward the field of textual criticism by apparatus criticism in general, and this particular exercise in apparatus a criticism. These contributions include accuracy of the critical apparatus, clarification of textual relationships, and knowledge of scribal habits.

- Chapter 5 concludes the work by summarizing the contents and calling for the discovery of the discrepancies which are likely to exist in the remaining New Testament manuscripts, and, most importantly, the rectification of them."

Rod writes:

- Over 200 of the 237 pages consist of a catalog of 1,520 "discrepencies" in codex W that are either not recorded in NA27 or which are recorded incorrectly. It appears that the vast majority of these (1,453) are simply instances of textual variations that are not part of a variant unit recorded by NA27. Only 67 are errors of citation. This is presented as a major flaw of NA27 which is "urgently" in need of correction.

- I'm curious as to the general assessment of this argument (by you and blog members). It seems a bit overdone to me, but I'd be glad for feedback from those in a better position to evaluate the value of this diss.

Tuesday, September 26, 2006

Palmer on LXX Zechariah

Since he's going to be a missionary, he's also had to make the decision not to spend the time preparing his Cambridge PhD thesis for publication. However, lest this opus be lost to the world parts of it can be accessed in two ways:

1) A long abstract will appear in the Tyndale Bulletin 57.2 (2006) 317-320 (PMH will correct me if any details are wrong).

2) A shorter abstract and table of contents appear below. Though I haven't read the work I can vouch for James' diligence and am sure it is a work that can be read with much profit.

Title: 'Not made with tracing paper': Studies in the Septuagint of Zechariah. Supervisor: Prof. R.P. Gordon, Cambridge University, 2004.

Abstract

The first part of the study is concerned with arriving at a clearer estimation of the Greek translator of Zechariah, through a detailed study of aspects of his translation practice, and the second part seeks to explore certain theological themes and concerns within that framework. After the introductory chapter 1, chapters 2-4 attempt to draw a portrait of the translator of the book. In chapter 2 we start by considering the types of literalism which are possible in an ancient biblical translation, and state briefly how the translator of LXX-Zech fits within this typology. Chapter 3 looks at the different ways in which the translator dealt with words in his Hebrew Vorlage that he was apparently unable to comprehend. The excursus that follows demonstrates that more care is needed if we are to talk about the influence of the LXX-Torah on the vocabulary of LXX-Zech. Chapter 4 considers the process of transforming a written text into such a state that it could be translated, looking at the translator’s practice in the areas of vocalisation, discernment of sense and word division. The boundary between conscious and subconscious alterations to the text is seen to be very thin, if it was existent at all. Chapters 5, 6 and 7 explore more ideologically focussed themes in the translation, namely the importance of Jerusalem and the future orientation of blessing (chapter 5), the return of the Diaspora and the incorporation of the nations into the worship of the LORD (chapter 6), and the translation of language about God (chapter 7). It is concluded that the translator intended to translate the sense of the text as he understood it, showing neither a demonstrably conscious theological agenda, nor a concern to represent every detail of the Hebrew Vorlage.

Contents

Preface

Abbreviations

1 Midrash and the Text-Critical Use of the Septuagint

(a) Textual Criticism and the Septuagint

(i) Orientation

(ii) Ulrich

(iii) Aejmelaeus

(b) Midrash and the Septuagint

(i) Orientation

(ii) Schaper

(c) The Textual Evidence for Zechariah

(d) Argument

2 Both Literal and Free: The Paradox of Translation

(a) Literalism in Biblical Translation

(i) Barr

(ii) Tov

(b) Paraphrase

(i) Paraphrase of the Verbal Form

(ii) Change of Word-Class

(iii) Paraphrastic Shortening

(iv) Interpretative Paraphrase

(c) Stereotyping and Variety in Translation

(i) Elegant Variation

(ii) Interpretative Variation

(iii) Counter Examples

(c) Word Order

(d) Summary

3 Reading Without Dictionaries: The Semantic Understanding of the Translator of LXX-Zech

(a) Did the Translator Always Understand his Hebrew Vorlage?

(i) Untranslated Words

(ii) Contextual Guesses

(iii) Contextual Manipulation

(iv) Parallelism

(v) General Words

(vi) Etymological Renderings

(α) Root-Linked Renderings

(β) Etymological Guess

(b) Summary and Analysis

EXCURSUS Did the Septuagint Translation of the Torah Serve as a Lexicon in the Translation of Zechariah?

(a) Common Vocabulary

(b) Allusions

(c) Summary and Analysis

4 Believing is Seeing: Homonyms, Homographs and Word Division

(a) Homonyms

(i) The Translator’s Understanding of the Hebrew

(ii) The Immediate Context

(iii) The Wider Context

(b) Homographs

(i) The Translator’s Understanding of the Hebrew

(ii) The Immediate Context

(iii) The Wider Context

(c) Word Division

(i) The Translator’s Understanding of the Hebrew

(ii) The Wider Context

(d) Summary

5 ‘A Future and a Hope’: Jerusalem and the Restoration of Israel

(a) Jerusalem and the Restoration of Israel in the MT

(b) The Distinctive Emphases of LXX-Zech

(i) A Future Hope

(ii)(α) The LORD’s Return

(β) The Exiles’ Return

(iii) Jerusalem: The Apple of His Eye

(α) The Centrality of Jerusalem

(β) Counter Examples

(c) Summary

6 ‘Worship God in Truth’: The Return of the Exiles and Ingathering of the Gentiles(a) The Jewish Diaspora and the Nations in the MT

(b) The Distinctive Emphases of LXX-Zech

(i) The Exiles Will Return to Jerusalem

(ii) The Nations Will Join Israel to Worship the LORD in Jerusalem

(iv) The Canaanites Will Be Excluded

(v) The Influence of Israel Will Expand

(c) Summary

7 Euphemism and the Glory of God: The Theology of LXX-Zech

(a) The Doctrine of God in the MT

(b) The Distinctive Emphases of LXX-Zech

(i) Euphemism and the Visibility of God

(α) Previous Scholarship

(β) LXX-Zech 9:1

(γ) LXX-Zech 9:14

(ii) Euphemism and the Majesty of God

(α) LXX-Zech 12:10

(β) LXX-Zech 11:8

(iii) Two Powers in Heaven (LXX-Zech 13:7)

(d) Summary

8 ‘Not Made With Tracing Paper’: Faithful and Free Translation in LXX-Zech

(a) Summary

(b) Conclusions

Bibliography

Do we contribute to being misunderstood?

“We don’t have the original texts of the NT; we all knew this, of course, already while I was at Moody Bible Institute: that’s why we talked about the inspiration of the autographs. But I came to see that the absence of the originals, and our inability in places to know for certain what was in the originals, rendered the claim that the original texts were inspired more or less irrelevant. What good does it do to say these original texts were inspired if we don’t have them??”

What makes it so interesting is that Ehrman thinks that at this point he is engaging with what evangelicals believe. Although our Lord was misunderstood, I think that we evangelicals should not entirely wash our hands of how we are misunderstood, and Ehrman’s perception of what evangelicals believe is probably shared by many more. The two confusing terms in this passage are ‘texts’, ‘original(s)’, and the confusing phrase is ‘inspiration of the autographs’. As I have mentioned before, ‘text’ is normally defined as something immaterial, though in Ehrman’s sentence ‘We don’t have the original texts of the NT’ it clearly means ‘We don’t have the original material manuscripts of the NT’. The last two occurrences of the word ‘texts’ in this extract purport to represent evangelical belief, but evangelicals would not generally agree with the statement that ‘the original material manuscripts’ were inspired.

‘Original’ is a confusing term too. In earlier phases of English it has meant simply ‘origin’ as in John Owen’s ‘Divine Original’. It has also been common for people to talk of consulting the ‘original’ by which they mean text in the original language.

‘Inspiration of the autographs’ is indeed a phrase that is used by evangelicals, but is hazardously open to misunderstanding. Again it sounds like inspiration is attributed to a material entity. I would propose that we drop speaking of ‘inspiration of the autographs’ and speak of ‘inspiration on the autographs’. The phrase may sound awkward, but it makes clear that we’re not saying that there was anything magical about the papyrus. We’re talking about inspiration of sequences of immaterial words, which happened to be recorded on autographs, which were themselves very unimportant. Just as the transmission of the coding of DNA is what matters in biology, not the particular molecules configured to present the code, so it is the wording of scripture is important within a doctrine of scripture not the autograph manuscripts (though these are of course historically important as artefacts).

I’d recommend therefore the following clarifications of terminology.

Phrases to drop:

- inspired/inerrant originals/autographs

- inspiration of the autographs

- ‘We don’t have the original texts of the NT’

Phrases to adopt:

- inspired/inerrant wording/text

- inspired on the autographs

- ‘We do have the original text of the NT’ (if you believe that all original wording is preserved somewhere in the manuscript tradition)

New Book on Amulets

According to the review (by Lea T. Olsan), the book begins with pagan and early Christian amulets before focusing on the middle ages. Two points of interest from the review:

- "The very amulet recommended for inquisitor's protection by the authors of the Malleus maleficarum consisted of the words of Christ during the crucifixion written on a parchment in the shape of the measure of Christ."

I wonder if these amulets (later described as "found in so many amulets dating from the last decades of the fifteenth century and well into the sixteenth") have any explicit notation of the Seven words from the Cross (cf. our earlier discussion here); and what is this shape (could they be cruciform like one or two gospel manuscripts?)? - "Skemer provides examples of the use of the opening of the Gospel of John, the most frequently met biblical text written on amulets."

I had thought that Ps 90 was the most popular part of the Bible on amulets; so I would like to see all the evidence. But it raises the interesting possibility of a manuscript base for the delimitation of John's Prologue (cf. here).

Monday, September 25, 2006

Interview with Bart Ehrman

Editorial introduction

Prof. Bart D. Ehrman needs no introduction to this forum as his publications and especially his best-seller Misquoting Jesus have aroused considerable interest on this blog. Nor does it really need to be said that the perspective from which this blog operates and Prof. Ehrman’s own views differ somewhat. He describes himself as a ‘happy agnostic’. However, it is to be hoped that his participation here will lead to some clarification of positions and lead to more fruitful discussion in the future. Owing to the busy nature of Prof. Ehrman’s schedule he has been invited on the understanding that he should not be expected to answer questions placed in comments subsequent to this interview.

Prof. Bart D. Ehrman needs no introduction to this forum as his publications and especially his best-seller Misquoting Jesus have aroused considerable interest on this blog. Nor does it really need to be said that the perspective from which this blog operates and Prof. Ehrman’s own views differ somewhat. He describes himself as a ‘happy agnostic’. However, it is to be hoped that his participation here will lead to some clarification of positions and lead to more fruitful discussion in the future. Owing to the busy nature of Prof. Ehrman’s schedule he has been invited on the understanding that he should not be expected to answer questions placed in comments subsequent to this interview.PJW: So, Prof. Ehrman, what do you think is the best thing about being a New Testament textual critic?

BDE: When I started working seriously in textual criticism twenty-five years or so ago, the field was not at all what it is today. The vast majority of textual critics were technicians who were experts in many of the demanding technical aspects of the discipline. But they had no interest or ability in seeing or explaining how their studies related to broader fields within biblical or religious studies. After doing my dissertation I started realizing that it was impossible to do serious text-critical work without relating that work to such fields as NT exegesis, the social history of early Christianity, the development of early Christian doctrine, to such questions as orthodoxy and heresy, Christian apologia, the role of women in the early church, the rise of Christian anti-Judaism, and so on. Not only were these other fields important for understanding the transmission of the text of the NT, the textual data known almost uniquely by textual scholars were important for seeing developments in these other fields. For me, the most exciting thing about being a textual critic over the past 15-20 years has been seeing how textual criticism has moved beyond its myopic concerns of collating manuscripts and trying to determine some kind of “original” text to situating itself in the broader fields of discourse that concern an enormous range of scholars of Christian antiquity. Textual critics are uniquely situated to contribute to these larger concerns, meaning that now, finally, the work textual critics do can be seen as widely important and relevant, not simply of relevance to textual technicians.PJW: What do you see as your most important contribution to scholarship?

BDE: I think my early work on methods of manuscript classification that I developed in my work on the Gospel Text of Didymus the Blind continues to have a significant role to play. But my most important contribution, I think, was in my book The Orthodox Corruption of Scripture, where I tried to show the symbiotic relationship between the emerging textual tradition of the NT and the conflicts raging in the early Christian centuries between proto-orthodox Christians and “heretics.”PJW: Amongst the various books that you have written do you have any favourites?

BDE: They are like my children. I love them all! But I have to confess a particular tug at my heartstrings for Orthodox Corruption (as a serious scholarly book) and Lost Christianities (as a popular book). (I should note: I try to alternate between writing serious books for scholars and popular books for the Barnes and Noble crowd – and I think one of my contributions has been to show that a scholar can do both, without compromising scholarly integrity).PJW: You’re rather prolific as a writer. How many hours a day do you work and how long does it take you to write a book like Misquoting Jesus?

BDE: Well, it’s very hard to say how long it takes to write a book. In one sense, Misquoting Jesus was the result of 25 years of study. In another sense, it took me five or six months of additional reading to get ready to write it. The writing itself goes very fast. I’m an intense, focused writer. I can crank out 30-35 pages on a word processor in about six hours. But then I definitely need to take a break and get a work-out!PJW: What is it, do you think, that makes Misquoting Jesus such a success as a book?

BDE: To my knowledge, it’s the first time anyone has tried to make the recondite field of textual criticism accessible to an audience that knows nothing (NOTHING) about the field. People reading the book often don’t know that the NT was written in Greek, they don’t know what a manuscript is, they don’t realize that we don’t have the original writings of the NT, etc. I think the reason no one has tried to write a book like this before is because it is awfully difficult. How do you explain these things in a way that is true to scholarship, on the one hand, but interesting to a complete non-expert on the other? I decided early on that the only way to do it was to tell lots of stories and anecdotes, to keep the writing lively, to avoid all technical discussions, to show what really mattered about this field, to stress the very most interesting aspects of it. I know I’ve gotten in trouble for this – especially among textual critics who would prefer to talk technical language to one another rather than reach out to a broader audience (and also among scholars who aren’t textual critics but who feel like I went too far in making the field interesting). To them all I would say is that if there is a better way to write a book like this – they should do it!PJW: How would you respond to the suggestion that Misquoting Jesus only engages with popular notions of the inspiration of scripture? After all many Christians down history have believed in verbal inspiration and at the same time that they did not have copies that exactly reproduced the inspired words.

BDE: This book is not about inspiration. In it I do talk about my own former views about the authority of scripture, but I don’t ever make any statements (that I recall!) in which I try to lay out a scholarly view of inspiration – I’m not trying to teach a doctrine of inspiration! I begin the book (and end it) with comments about my own spiritual journey away from a view of Scripture that was taught in the evangelical circles I was associated with (I never claim that this was the only view of inspiration in evangelical circles, or other Christian circles; I simply refer to it as the view in the circles I was associated with): the view of “verbal plenary inspiration” (the Bible is inspired completely, in all of its very words).I begin with this autobiographical note in order to show what struck me as the deeper significance of what I came to understand the more I explored the manuscript tradition of the NT. We don’t have the original texts of the NT; we all knew this, of course, already while I was at Moody Bible Institute: that’s why we talked about the inspiration of the autographs. But I came to see that the absence of the originals, and our inability in places to know for certain what was in the originals, rendered the claim that the original texts were inspired more or less irrelevant. What good does it do to say these original texts were inspired if we don’t have them??

For some people this is no problem, and if so – well, what can I say? Most non-evangelicals realize that it is in fact a problem. But if it’s not for someone else, who is an evangelical, well, I think maybe that person and I look at the world differently! (By the way, in direct response to the question: I don’t mean to deal “only” with “popular” notions of inspiration. I deal with one form of the notion – the one that I, and other evangelicals that I knew, used to have. But I must say that this way of putting the question also strikes me as odd: since this book is meant for a popular audience, why would I deal with a view of inspiration that is not popular?? In any event, I’m not making any universal claims about inspiration; I’m simply saying why I can personally no longer subscribe to the evangelical views that I once held.)

PJW: You wrote: ‘The more I studied the manuscript tradition of the New Testament, the more I realized just how radically the text had been altered over the years at the hands of scribes, who were not only conserving scripture but also changing it.’ (Misquoting Jesus, p. 207). Do you think the same could be said relative to the textual transmission of Classical literature?

BDE: I’m not quite sure what the question is after: is it asking whether I realize that other texts besides the NT were changed in the process or transmission? Uh, I am a scholar, not an idiot!There is an interesting issue, of course, of whether classical literature was changed as much as the NT was. I don’t know the answer: we don’t have anything like the manuscript tradition for the classics (even Homer!) that we have for the NT.

Another interesting aspect of the question is that the copying practices of classics and sacred Scripture may have been different. Kim Haines-Eitzen has made a compelling case that Scripture in the early centuries of the church was principally being copied by scribes who wanted to use the copies themselves, whereas the classics in this period were copied by scribes for the use of other people. That no doubt affected the process of transmission of scripture (it is the reason, within the NT textual tradition, that harmonization is so prevalent, as are the elimination of apparent inconcinnities and errors, etc.)

But maybe I’ve misunderstood the question!

PJW: Do you think that anyone might ever come away from reading Misquoting Jesus with the impression that the state of the New Testament text is worse than it really is?

BDE: Yes I think this is a real danger, and it is the aspect of the book that has apparently upset our modern day apologists who are concerned to make sure that no one thinks anything negative about the holy Bible. On the other hand, if people misread my book – I can’t really control that very well. Maybe ironically, this could show the fallacy of the view also held widely among evangelicals (at least the ones I know), that the intention of an author dictates the meaning of a text (since my intentions seem to have had little effect on how some people read my text).My book is about how the NT got changed by the scribes, and here I insist that there are certain things that can be stated as factually true. I try to state these things as clearly as I can in the book. There are over 5000 Greek mss of the NT. These all differ from one another. The differences number in the hundreds of thousands. The vast majority of these differences are completely immaterial and insignificant and don’t matter for much of anything. But some of the differences are very significant and can change the meaning of a passage or even of an entire book. Is there any textual critic who can say that these are not facts?

Still, I know that some evangelicals have raised objections to the book (oddly enough, I don’t know of serious objections raised by non-evangelicals. Or have I missed something? If only evangelicals are concerned, is that because only evangelicals care? Or is it because only they are threatened? If threatened – threatened by what exactly??). Many of the objectors have complained that readers of the book may not read those several strongly worded passages where I emphasize that MOST of the changes don’t matter much, and that they will instead notice only the passages where I discuss significant changes. To this kind of objection I really don’t know what to say. If people can’t read what I say – well, what can I say??

PJW: How do you view fellow textual critics who are evangelicals?

BDE: Hey, some of my best friends are evangelicals! I’ve published books with Michael Holmes and Gordon Fee, and in the guild, there are very very few textual critics of the NT who are not evangelicals! What do I think about them? Well, I like most of them! What do I think about their views? Well, I think their theology is wrong and I personally find their views untenable. And they find my views untenable. Isn’t scholarship great?!PJW: What are your medium or long-term publication goals?

BDE: Right now I’m working on an edition of the apocryphal Gospels: original text on one side of the page (Greek/Latin/Coptic) with fresh facing page translations. It’s a lot of work and is meant, obviously for scholars (it’s a “Loeb-like” edition, but it will be done by Oxford, rather than Loeb). I’m doing it with my colleague Zlatko Plese, a brilliant classicist and Coptologist.I have a whole list of other books I’ll be working on in the next couple of years, some of them scholarly (a commentary on some second-century apocryphal Gospels for the Hermeneia Commentary series) and some of them popular (a discussion of biblical traditions that deal with the problem of suffering). I like doing a range of things in my publications, for a range of audiences, and plan to continue full hilt for the time being.

PJW: Thank you Prof. Ehrman for taking time to respond to these questions

BDE: My pleasure!Links:

Friday, September 22, 2006

Scots NT without John 21

I've just been reading through W.L. Lorimer's The New Testament in Scots (1983). Lorimer was Professor of Greek at the University of St Andrews and his translation of the NT is characterised by a number of independent textual decisions. At the end of the NT he gives four 'spuria', which are not found in the main body of the translation: Mark 16:9-20; John 7:53-8:11; 21:1-25; 2 Corinthians 6:14-7:1.

I've just been reading through W.L. Lorimer's The New Testament in Scots (1983). Lorimer was Professor of Greek at the University of St Andrews and his translation of the NT is characterised by a number of independent textual decisions. At the end of the NT he gives four 'spuria', which are not found in the main body of the translation: Mark 16:9-20; John 7:53-8:11; 21:1-25; 2 Corinthians 6:14-7:1.To give you a taste of the translation, here's John 18:18: 'The servans an Temple Gairds hed kennelt an ingle an war staundin beikin forenent it, for it wis cauldrif; an Peter stuid wi them an beikit an aa.'

As far as I know this is the only printed NT that seeks to exclude John 21.

Thursday, September 21, 2006

Picture of earliest ms of 1 Peter

Checking Patristic Citations

Question: how do you track down the references to check on patristic citations cited in NA27?

My Answer: good question, I'm not familiar with any easy way to do this (and it is even worse in UBS4 which has expanded patristic support, but no indications of source material). [I have expanded my actual historical ipsissima verba answer with some things I have thought of in writing]

- Basically if the passage is in the Catholic Epistles then the ECM gives references and supporting evidence.

- If it is in Luke then the IGNTP gives references and page numbers in editions.

- If it is in Matthew or Mark then Legg gives selections of texts with some reference (although it doesn't always seem complete).

- Otherwise check Tischendorf 1869 (but you have to figure out his referencing system and then you may have to check an old edition of the cited work; and remember that not all patristic works have standard referencing conventions).

- Also try Tregelles 1857-1879 (Tregelles aimed to collect all the patristic evidence of the first three centuries, the 'early Citations' 'with full references to the passages in the works themselves').

- If none of these help (or are available) then start at the other end with the Biblia Patristica which indexes scripture citations in church fathers.

- If it is a controversial passage references (and discussion) can often be found in the secondary literature (detailed commentaries of the type that discuss the text and/or journal articles etc.).

- Remember that TLG is fairly well stocked with Greek patristic literature which can be searched for specific word combinations.

- Further info, method discussion and bibliography check the essay in the Metzger Festschrift ed. Ehrman & Holmes.

Bibliographical Up-date:

ECM = Novum Testamentum Graecum - Editio Critica Maior (Institut für Neutestamentliche Textforschung, Münster); Vol. IV Catholic Letters, ed. by Barbara Aland, Kurt Aland†, Gerd Mink, and Klaus Wachtel.

- Instl. 1: James, Pt. 1. Text, Pt. 2. Supplementary Material, Stuttgart 1997; 2nd rev. impr., Stuttgart 1998, ISBN 3-438-05600-3

- Instl. 2: The Letters of Peter, Pt. 1. Text, Pt. 2. Supplementary Material, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-438-05601-1

- Instl. 3: The First Letter of John, Pt. 1. Text, Pt. 2. Supplementary Material, Stuttgart 2003, ISBN 3-438-05602-X

- Instl. 4: The Second and Third Letter of John. The Letter of Jude, Pt. 1. Text, Pt. 2. Supplementary Material, Stuttgart 2005, ISBN 3-438-05603-8

Legg = S.C.E. Legg, Novum Testamentum Graece, secundum textum Westcotto-Hortianum, Evangelium Secundum Marcum: cum apparatu critico nouo plenissimo, lectionibus codicum nuper repertorum additis, editionibus versionum antiquarum et patrum ecclesiasticorum denuo investigatis (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1935); and S.C.E. Legg, Novum Testamentum Graece, secundum textum Westcotto-Hortianum, Evangelium Secundum Mattheum: cum apparatu critico nouo plenissimo, lectionibus codicum nuper repertorum additis, editionibus versionum antiquarum et patrum ecclesiasticorum denuo investigatis (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1940).

Tischendorf 1869 = Novum Testamentum Graece Ad antiquissimos testes denuo recensuit, apparatum criticum omni studio perfectum apposuit commentationem isagogicam praetexuit Constantinus Tischendorf (Lipsiae: Giesecke & Devrient, 1869; 8th ed.) On-line (jpg images - menu driven): http://rosetta.reltech.org/Ebind/docs/TC/ (scroll down a bit)

Tregelles = S.P. Tregelles, The Greek New Testament, edited from ancient authorities, with their various readings in full, and the Latin version of Jerome (London: S. Bagster & Sons: London, 1857-79)

Biblia Patristica = Allenbach, J. ...[et al.]., ed. Biblia Patristica: index des citations et allusions bibliques dans la littérature patristique (7 vols; Paris: Éditions du Centre national de la recherche scient, 1975-2000).

- v. 1 covers the first two centuries

- v. 2 covers 3rd century, omitting Origen

- v. 3 Origen

- v. 4 Eusebius, Cyril of Jerusalem & Epiphanius

- v. 5 Basil of Caesarea, Gregory of Nazianzus, Gregory of Nyssa & Amphilochius

- v. 6 Hilary of Poitiers, Ambrose of Milan & Ambrosiaster Supplement: Philo

- v. 7 Didyme d’Alexandrie

If you go here and scroll down there is a useful guide to the entries in BP.

TLG = The Thesaurus Linguae Graecae (TLG®) is a comprehensive digital library of Greek literature from Homer to the fall of Byzantium in AD 1453. See: Luci Berkowitz and Karl A. Squitier, Thesaurus Linguae Graecae Canon of Greek Authors and Works (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990; 3rd); On-line: http://www.tlg.uci.edu/ (needs subscription, institutional or individual)

UPDATE 2013 (TW):

Here are two additional resources for patristic citations:

Wednesday, September 20, 2006

Orr on Lundbom on LXX Jeremiah

As a undergraduate I have been recently exposed to the wonderful world of text-criticism. One of the cases I have spent a little bit of time looking at has been that of Jeremiah in the LXX and MT. I thought your readers might be interested in a summary of some of Jack Lundbom’s work on this subject.

Lundbom has argued that haplography has affected the LXX of Jeremiah to an extent that has not been recognised before and that severely questions its quality as a text. In a 1999 article with David Freedman he examined Jeremiah 1-20 and argued that there are around 50 cases of haplography in LXXV. When he came to write his commentaries on Jeremiah 21-52, he imagined he would find more expansion in the MT since the section contains more prose. However, he actually found an additional 278 cases of haplography in the LXX. This gives a total of 330 losses in LXX due to haplography - ‘an extraordinary number by any measure’.

Lundbom does acknowledge that some haplographies are clearer than others. So he points out that in Jeremiah 5:15 of the MT we read: גוי איתן הוא גוי מעולם הוא גוי לא־תדע לשנו. If we retrovert the LXX it reads: גוי לא־תדע לשנו. This seems to be a clear case where the scribe’s eye skipped from the first to the second גוי. However, in Jeremiah 1:15 we read: לכל־משפחות ממלכות צפונה in the MT, while in LXXV משפחות is missing. It is not altogether clear if this is a case of the secondary addition of the text under the influence of Jeremiah 25:9 where the word משפחות appears in a similar context; a conflation of two variant readings since משפחות and ממלכות are interchangeable elsewhere (cf. Jeremiah 10:25 and Psalm 97:6) or in fact a case of haplography where the scribe skipped from the מ of משפחות to the מ at the beginning of ממלכות. Lundbom argues that while each case should be investigated individually, haplography should be the default explanation since expansion is ‘complex and difficult both to pin down and explain, since it requires an inquiry into the mental operations of a scribe’. With haplography, we have ‘a well-established and perfectly objective text-critical method [by which] a considerable number of differences between the two texts can be explained’. In many of these cases, such as the above, there may be no way to settle the issue, but Occam’s razor should prevail and ‘parablepsis is a better solution than its alternative’.

Far from having a superior text, Lundbom concludes bluntly that ‘the LXX translator(s) of Jeremiah had the misfortune of working from a “bad Hebrew Bible”’ and that we should be ‘glad that more Jeremiah passages were not quoted by writers of the NT, for whom the LXX Bible was normative’.

Lundbom has recently published a summary of his work: ‘Haplography in the Hebrew Vorlage of LXX Jeremiah,’ Hebrew Studies 46 (2005): 301-320.

I was wondering what your readers think of both his conclusion regarding Jeremiah in the LXX and his contention that we should prefer the ‘objective’ explanation of haplography by default.

Tuesday, September 19, 2006

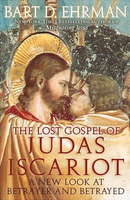

Ehrman, Lost Gospel of Judas

I've just received an offer from Oxford University Press of a free copy of Bart Ehrman's new book The Lost Gospel of Judas: A New Look at Betrayer and Betrayed (OUP: October 9th, 2006). They say: "As a previous reviewer of Ehrman's books, we invite you once again to take part in evaluating the engaging insights of Bart Ehrman, one of the most respected authorities on early Christianity."

I've just received an offer from Oxford University Press of a free copy of Bart Ehrman's new book The Lost Gospel of Judas: A New Look at Betrayer and Betrayed (OUP: October 9th, 2006). They say: "As a previous reviewer of Ehrman's books, we invite you once again to take part in evaluating the engaging insights of Bart Ehrman, one of the most respected authorities on early Christianity."I've only ever reviewed Ehrman on this blog, but it's good to know that OUP have noticed.

Their publicity says:

As you may recall, Ehrman is the author of The New York Times

bestseller Misquoting Jesus, the groundbreaking book that shed light

on the many mistranslations and alterations the Bible has undergone

since its inception. In his newest book, Ehrman promises to be just as

controversial, detailing the events and consequences surrounding the

discovery of the lost gospel of the man believed to be history's most

notorious traitor.

Discovered in a pizza parlor in a Swiss town near lake Geneva, the

Gospel of Judas is perhaps one of the most important and controversial

discoveries of the 20th Century. In The Lost Gospel of Judas

Iscariot, bestselling author Bart D. Ehrman analyzes the impact of

this find, and what it tells us about the life of Judas. A provocative

and compelling account, The Lost Gospel of Judas Iscariot shakes the

very foundations of everything we thought we knew about the man who

betrayed Jesus Christ.

There appears to be no shortage of sensationalism here. I would like, however, to take this opportunity to encourage people to wait a little bit longer for the next OUP book on the Gospel of Judas, which will be by one of our own bloggers, the venerable Simon Gathercole, who should give us plenty of philological learning as well as sound judgement on the subject.

Coptic Digital Resources

[N.B. I am now keeping this list up-to-date on my personal website (here). Unfortunately, Blogger did not allow me to edit this list for several months, so I had to make the move.]

Coptic is the final phase of the Ancient Egyptian language which began in the 3rd century. After the Muslim conquest of 642, Sahidic Coptic becomes the nationalistic and religious language of native Egyptians. Several other regional dialects are prominent (Fayumic, Akhmimic, Sub-Akhmimic, Middle Egyptian, etc...). By the 9th century, Coptic is replaced in the documentary papyri by

Listed below are the main internet resources for the Coptic language. If anybody else knows of good ones, please post them and I will update this list.

Bibles

Nova Sahidica parallel Coptic and Greek Text

A downloadable Coptic-Arabic New Testament (Bohairic, free)

Coptic New Testament, lectionary and dictionary CD (All dialects, $50)

Sahidic New Testament and Nag Hammadi, PHI CD # 7 (free)

Logos Sahidica Parallel GNT and dictionary ($89.95)

E-Sword Sahidic New Testament (Free) This is the only resource now available which is in unicode.

Remenkimi – NT and OT in Bohairic and Sahidic

Fonts

Coptic Standard Fonts

St-Takla.org Coptic Fonts

Moheb Mekhaiel' Coptic Unicode Page

How to enter Coptic Unicode (Donald Mastronarde

Organizations/Websites

Grammar/Learning the Coptic

Ambrose Boles Links Ambrose is training to be a doctor, but has a nice collection of Coptic resources on the web. A couple have been developed by him and are especially useful for the New Testament.

Lance Eccles' Resources Lance has created some wonderful surveys of grammatical forms and construction helpful to the beginner and more advanced student.

Heike Behlmer's Coptic Dialects Bibliography

Peter Williams' Coptic Bible Bibliography

A Key to the Exercises in Lambdin’s Coptic Grammar

Dictionaries

Crum's Dictionary This is the standard in Coptic research. It has recently been republished by Wipf and Stock.

Downloads

Koptische Grammatik by M. G. Schwartze (Berlin, 1850)

Sub-Akhmimic of John by Herbert Thompson (London, 1924)

Other Databases

The Duke Papyrus Archive: Coptic

CMCL (Corpus of Coptic Literary Manuscripts) This is Tito Orlandi's database of Coptic Literary texts. Subscription costs 180 Euro, but apparently the database holds everything a person could want to read in Coptic.