Saturday, July 29, 2006

Novum Testamentum Patristicum

Thursday, July 27, 2006

Leon Lamb Morris (15.3.1914 – 24.7.2006)

Yet more from SNTS

I've been acquiring lots of books. I did not previously know about:

Bernhard Mutschler, Das Corpus Johanneum bei Irenäus von Lyon (WUNT 189; Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2006). XV + 629 pages, which I couldn't resist.

Prof. Tjitze Baarda (Amsterdam) kindly gave me a copy of his book, Early Transmission of Words of Jesus: Thomas, Tatian and the Text of the New Testament (VU Boekhandel, 1983), which is a collection of his essays.

The textual criticism section today was Josep Rius-Camps giving a paper entitled 'The Pericope of the Adulteress Reconsidered: The Nomadic Misfortunes of a Bold Pericope'. The thesis was, to say the least, unusual and I cannot say that everyone was convinced (understatement). He argued that the PA was originally part of Mark, whence it got into Luke. It was then chopped out of Mark and Luke, was transmitted separately for a wee while and then put into John. The evidence that it comes from Mark, I hear you asking: the PA in D (Bezae) contains 3 historic presents and these are often found in Mark.

More live from SNTS

He proposed emending James 2:1 to omit 'Jesus Christ' so that the whole letter could be read as by someone who followed Jesus Christ (1:1) but was feigning to write to Jews (12 tribes of 1:1) who were wider than just followers of Jesus.

Larry Hurtado picked him up on his cavalier emendation—the main reading of NA27 explains the other readings. Kloppenborg seemed to find the Greek construction so amazingly difficult that emendation had to be used.

The news on the ground is that Cambridge have now appointed their new chair of New Testament. I'm not sure yet whether I am able to announce the name.

Wednesday, July 26, 2006

Ethiopic Gospel of John

Wechsler, Michael G., Evangelium Iohannis Aethiopicum, CSCO 617, Leuven: Peeters, 2005.

with an introduction, mentioning the kind of text Eth John reflects (mixed, as you might have guessed). The main corpus is a critical edited text of Eth John, based on the earliest Ethiopic MSS. Besides, an additional chapter lists minor variants, and another one has suggestions for the NA27 text, in Greek (for that, you do not need Ge'ez!).

It seems to be a thoroughly edited work, which will be very helpful in the future editions of the IGNTP / ECM Gospel of John volumes. In the foreword, he acknowledges, besides others, the help of R. Zuurmond (who edited Eth Mark & Matthew) and of God (who, according to him, seems to have been somehow involved in the production of the Greek Vorlage ...).

Anyone who wants to know more about the Ethiopic Bible: Take a look at the Encyclopaedia Aethiopica, Vol. I and II are now out (Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden). Look for the article "Bible" in Vol. 1. Very helpful.

Live from SNTS

We have other some interesting textual critics here including J.K. Elliott, Tjitze Baarda, Ulrich Schmid, and Mike Holmes.

This morning H.-G. Bethge (Berlin) gave a report on the Gospel of Judas and Larry Hurtado spoke about a volume he has edited on the Freer Biblical Collection.

I picked up the 450 page Festschrift for Heinrich Greeven, Studien zum Text und zur Ethik des Neuen Testaments for £7 from De Gruyter.

If you wish to see famous NT scholars then watch our webcam here. It points down at the area just outside where our book display is. Coffee times are around 11 a.m. and 4 p.m. and it is at this time that some delegates will spill out onto the grass. However, you would probably have to have eagle eyes to recognise any of them.

Monday, July 24, 2006

Open access at Leiden

Take the following articles by de Jonge:

'Erasmus und die Glossa Ordinaria zum Neuen Testament'

'Erasmus' New Testament Translation Method'

In fact there are no fewer than 119 titles by de Jonge available here. But I also saw one piece by J. Delobel and if one were to search the facility I'm sure that more relevant material would emerge.

SNTS in Aberdeen

Saturday, July 22, 2006

How not to compile an index

A general index (of names of scholars and subjects combined) and an index of textual variants is provided. In both cases it would appear that they were constructed by computer without the benefit of sufficient human intelligence in the editing.

The index of textual variants follows a strictly alphabetical version of numerical order (e.g. 1, 10, 16, 2, 21, 3, 4, etc.) rather than the natural numerical order we should expect.

The general index included a rather full listing of sixteen page references next to Head, Peter, auguring well for some sustained dialogue (I presume I am not alone in occasionally checking an index to see whether I have made it into the discussion). Alas, most of them merely include the word ‘head’ somewhere on the page. I wondered whether it was only parts of the body that merited such treatment, or whether I was being singled out for some reason (disturbingly, the second and third of the references to me in the index refer to ‘the head of an ass’). An investigation of other potentially ambiguous names(‘Brown’, ‘Farmer’, ‘Gamble’, ‘Grant’, ‘Lake’, ‘Riddle’, ‘Tune’) uncovered a series of other errors: the first two references under Brown, Raymond p. 85 & 86, actually refer to Milton Brown, who has no index entry; one reference under Grant, R.M. p. 219 is to the verb ‘to grant’; five of the thirteen references under Lake, Kirsopp p 45, 85, 88, 253, 254 are actually to ‘Salt Lake City’; one reference under Riddle, D.W. p. 206 is to a ‘riddle’ which ‘remains unsolved’; two out of three references under Tune, E.W. are to a musical ‘tune’ p. 8, 78). To my mind this is not adequate; computers are very helpful, but they are not intelligent, for intelligence we need people, but in this respect the key people, both author and publisher, have failed to exercise sufficient critical control and intelligence.

Friday, July 21, 2006

Oxyrhynchus on TV

Documentary about an archaeological discovery in Egypt a hundred years ago that revolutionised our attitudes to the Ancients. It comprised over half a million documents which included not only the lost works of the giants of Greek literature such as Homer, Sophocles and Sappho, but also records of daily life that offered a unique window onto a lost world. New technology developed by NASA promises to reveal some of the most significant finds to date.

Worth watching if you get a chance (or can borrow a video). Makes papyrology look interesting (and complex). Lots of talking Profs from Oxford, UCL etc. (esp. Dirk Obbink). Reconstructions of Grenfell & Hunt etc. Great pictures of Obbink opening up one of the 800 boxes of unedited papyri and looking inside. Repeated claim was that perhaps 500,000 fragments were unearthed and brought to Oxford; so only around 1% have been published so far. Focused on Greek literary texts (Menander, Sappho, Sophocles etc.), nothing on Bible (one small bit on Gospel of Thomas which ended up talking about the Coptic text - which is not from Oxyrhynchus!). Ended up with section on multi-spectral imaging which was interesting.

Thursday, July 20, 2006

Complutensian Polyglot

Wednesday, July 19, 2006

Number of possible variants

Such use of numbers is something we have reflected on before (here). Statistics have long been in use in estimates by textual critics of the reliability of the NT transmission. Numbers of variants were important to Bentley and percentages to Westcott and Hort. More recently Ehrman has found the number of variants in the NT (200-400 thousand?) to be significant, but from a different perspective Norman Geisler would cite 99.5% accuracy for NT transmission.

Such use of numbers is something we have reflected on before (here). Statistics have long been in use in estimates by textual critics of the reliability of the NT transmission. Numbers of variants were important to Bentley and percentages to Westcott and Hort. More recently Ehrman has found the number of variants in the NT (200-400 thousand?) to be significant, but from a different perspective Norman Geisler would cite 99.5% accuracy for NT transmission.One reaction could be to run from all use of numbers, but if we are not to be too dismissive we may at least ask what legitimate ways there are of using them.

Byzantine to Alexandrian correction?

"Maurice Robinson's textual theory holds that the Byzantine text best represents the Original Text of the NT, and that all other text-types are corruptions thereof. Many MSS show evidence of being corrected by a scribe who for whatever reason gave up his project partway through the corpus. Are all of these Alexandrian-to-Byzantine corrections, or, as would be expected if the Alexandrian text-type reigned supreme at some time and place in the history of textual transmission, do some MSS show evidence of an interrupted Byzantine-to-Alexandrian correction process?"

Timpanaro on Lachmann II

Tuesday, July 18, 2006

Update Greg.-Aland 2483

Codex E 07

1. This is a very helpful, thorough and useful article. Take a pen right now and make a note in your copy of Elliott's Bibliography of New Testament Manuscripts - you do not want to discuss this manuscript without reference to this article.

2. It is not only about Codex E/07 actually. It is about Basil. Gr A. N. III. 12 - the whole codex in its current form - which is primarily Codex E, but also contains 2087 - portions of Revelation written into spaces on a couple of pages during the twelfth century; and some other replacement leaves from the 14th cent (these have not been assigned a separate number - curiously?), which re-use old leaves (palimpsests). Palau identifies one of the under-written texts for these leaves (folio 207: fragment of Ephraem Syrus in Greek), but the other two contain different unidentified ninth-century Greek texts (folios 160, 214 - there is an invitation for the curious!).

3. Palau provides ten plates (incl. pictures of the binding and other decorations as well as text: fol. 3 = Matt 1.1-6; fol. 24 = Matt 8.19-24; fol. 45 = Matt 13.54-14.2; fol. 96v = Matt 28.16-20; fol. 98 = Mark 1.1-6; fol. 248 = kephalaia for John & Rev 4.8ff in 2087; fol. 249 = John 1.1-10).

4. For the keen there are untold details about quire formation, ruling systems, the decadent form of 'maiuscola biblica' evident here, abbreviations, accentuation, punctuation, decorations, etc. I won't even attempt to summarise that here. There is also a lot of material on the history of the manuscript. Some of this, especially the decorated titles and other elements, are of interest in relation to the reception history of the NT - Codex E/07 is an early example (perhaps the first if 8th cent) of decoration using a full page cross and the inscription IS XS NHKA ('Jesus Christ conquers').

5. Palau argues against the universal consensus - of an eighth century date - in favour of a later, ninth century date. The grounds for this are several (although none stem from a directly palaeographical judgement about the hand - she notes that Cavallo places it early in the 8th cent):

- a judgement about the place of this text in the history of the development of accentuation: 'The abundance and regularity of the accentuation suggest a date in the 9th C.' (p. 479). There is no proof or discussion of this point.

- A further point, which is actually the critical one, is that the abundant colourful decoration is uncharacteristic of the eighth century (see p. 464, cf. pp. 481-485 which deal with decoration and 486). Rich ornamentation is infrequent in the eighth century manuscripts available to us, mostly they have simple embellishments and uncomplicated initials.

- Parallels in borders, mosaics and depictions of the cross in the decorations, combined with some Latinising elements in decorations suggest a place of origin in Northern Italy, perhaps Ravenna.

- 'My conclusions are that the manuscript was copied by a non-Greek, probably Latin scribe, in the 9th c., in an Italian location subject to a strong Byzantine influence.' (p. 506)

6. Palau doesn't approach this from a NT text critical perspective. She accepts the work of Chapman, Geerlings and Wisse on Family E without any substantial interaction: this ms 'is in fact family E's most ancient member and can therefore be considered the most prominent specimen of the group, although not the best codes of the family nor its archetype' (p. 472). Her theory of date and provenance could usefully be followed up by a treatment of the family E manuscripts with a view to codicological and presentational similarities.

7. All in all a good piece of work which raises several research issues for NT text criticism:

- Two unidentified palimpsest sheets to investigate.

- The place of NT manuscripts in the history of the development of accentuation.

- Codicological analysis of Family E manuscripts.

- The use of the cross in NT manuscript decorations as an aspect of NT reception history.

Payne Smith online

Index Locorum

Cornwall and Textual Criticism: Those were the days ...

Cornwall is without doubt one of the loveliest parts of England (my own high opinion of it may be due in some measure to the fact that it resembles the Victorian coastline): sand, surf beaches (click here for surf reports Dave Black take note); rocky coastlines; lovely walks and views (for the view near St Gerrans see here). But it is a long way from decent libraries.

This last was not a problem to Scrivener: 'My other labours relating to textual criticism of the New Testament have been carried on chiefly in a remote corner of Cornwall, whither the liberality of their owners has permitted me to bring many manuscripts for thorough and leisurely examination.' (from the Addendum to the Introduction to his Codex Bezae Cantabrigiensis [1864], lxiv).

So I'm just composing a note to the librarian: 'Following ancient scholarly custom I would like to take a couple of priceless fragile biblical manuscripts down to the beach for the summer "for thorough and leisurely examination"'. How do you think I'll get on?

Monday, July 17, 2006

Select your favourite posts

Saturday, July 15, 2006

Rodgers on Hebrews 10:38

Vleugels on Apostles' Creed

One of our bloggers, Gie Vleugels, has just produced a book on the Apostles' Creed entitled De Leer van de Twaalf (the Teaching of the Twelve—no, this is not a book about the Didache).

One of our bloggers, Gie Vleugels, has just produced a book on the Apostles' Creed entitled De Leer van de Twaalf (the Teaching of the Twelve—no, this is not a book about the Didache).More details here and on the Evangelische Theologische Faculteit, Leuven's webpage.

Thursday, July 13, 2006

Here and there among the blogs

Julian Jensen has started a blog called Text Crit which seems to be going to focus on computers, technology and biblical textual criticism.

M. Leary has an interesting recent post about the Penn Papyri Project, and (hopefully) ongoing posts about his work on Book Culture in Early Christianity (ekthesis - cool name for a blog).

Rob Bradshaw republished a short piece by F.F. Bruce on the (Chester Beatty Papyri ) [which is both interesting and pretty dated as it comes from 1934].

Blogs, Article reviews, Scholarship, and Accessibility

For example, an article review or response is often very helpful for a wider audience but seldom makes it into print. Our blog is of course interesting for those who are following it closely, but how many people will find PMH's critique back in two months time?

Activities at the Complutensian University Further Explained

On 12-13 June, I was invited by Julio Trebolle-Barrera to attend a workshop at the UCM on the Books of Kings (III-IV Kingdoms). My work is on the non-LXX Greek (or, Hexaplaric) readings in Kings, so he invited me to be part of the meeting. There were only two other participants there, besides Julio, Andrés Piquer Otero (also the editor of 2 Kings for the new Oxford Hebrew Bible), and Pablo Torijano Morales. The Madrid team presented their current work in progress, this polyglot of Kingdoms and we had two days of intensive discussion about text history, textual criticism, and other matters pertaining to the text of III-IV Kingdoms. By the way, it should be noted that this is a work independent of the team at CSIC (i.e., Natalio Fernández Marcos’ team).

The project in which they are engaged began with the motivation to assist the preparation of the Göttingen LXX of III-IV Kingdoms, of which Trebolle and Torijano are the editors. The polyglot places six columns to the left of the layout and six columns to the right. There is the option for adding more columns, particularly if they are able to get funding to transform this into an electronic database. At present, however, they have omitted columns like the Syrohexapla. At any rate, the left side of the layout has six columns that are relevant to the text history of the Greek tradition. Thus, from left to right: Georgian, Armenian, Old Latin, Lucianic, B (Rahlfs), and Hexaplaric readings. In fact, to begin with, they were going to ignore the Geo and Arm texts because of uncertainty as to whether or not they would help clarify the picture. However, after discussions with R. Hanhart in Gottingen, they decided that more attention should be paid to the Armenian and Georgian texts. After some preliminary studies, it is surely a good thing that they did. On the right side, the six coumns which are relevant to the Hebrew tradition are: MT, Targum, Peshitta, Vulgate, Chronicles Parallels, and Varia (where Josephus, Syrohexapla, and/or Hebrew mss. variants might be listed).

As the abstract mentioned, the readings are colour-coded to show resemblances and divergences. It is a brilliant method, and one thing emerging early on is the relationship between Geo and Luc., a relationship which in many cases goes against the assumption that Geo and Arm are both so closely related as to be irrelevant for the purposes of text criticism of the LXX. It will be interesting to see how Geo and Luc continue to relate once the editors move from the Kaige section of III Kingdoms. Also of note, Arm’s relationship to the Hexaplaric recension is beginning to show itself diverging from the standard assumptions.

The aim is to have chs. 1-12 of I Kings (III Kingdoms) published by 2007-8. This might not happen, however, because progress is slow. A few more notes to mention:

1. Pablo is collating several Arm mss. that were NOT used by Zohrabian in his Bible of 1805. These mss. are providing him with an ad hoc critical text that will be a better base to work from than Zohrabian. So, while he is not creating an Arm Kings critical edition at the present, he could later publish these books, since he is making a critical apparatus for his own purposes. What will be inserted into the Polyglot will be his text, but obviously without his apparatus. His apparatus is brilliant, and would be a gem to have later on.

2. Andres is likewise working on new Georgian witnesses. All that was said of Pablo in #1 can equally be applied here.

3. I am gratefully supplying the Hexaplaric readings for the Hexaplaric column. That is not to say they are not also working on these readings. But, with the expertise they bring to the Arm and Geo texts, I am hopeful that I will have a better chance at obtaining some interesting results. Further, since I am preparing a critical text of these Hexaplaric readings, I can assist them in obtaining the most reliable readings.

4. Again, the critical text of the Gottingen III-IV Kingdoms is the ultimate goal of the Madrid team. This has its own problems of which they are exasperated with at the present.

The sum of the matter is that at some point in the next 5 years, we will have:

1. A Polyglott presentation of the Versions for III-IV Kingdoms,

2. A critical edition of the Hexaplaric readings for III-IV Kingdoms,

3. At least the seeds for a critical text of III-IV Kingdoms in Geo and Arm, and

4. A critical edition of the LXX of III-IV Kingdoms.

Other Early Christian Gospels

Here is their blurb and the table of contents:

Since the late nineteenth century, our knowledge of early Christianity and its literature has been improved significantly by the recovery of numerous ancient manuscripts. Among the most important finds are the Greek manuscripts that preserve portions of little-known early Christian gospels, such as the "Gospel of Thomas", the "Gospel of Peter", and the "'Unknown Gospel' of Egerton Papyrus 2". These fragmentary manuscripts provide us with direct access to texts that seem to have been written at about the same time as the New Testament gospels. They allow us to study ancient writings about the life of Jesus in their original language, without the filters of later translation or commentary. They make long-forgotten gospels penned by some of Jesus' earliest followers available once again, shedding new light on the formative years of Christianity and, perhaps, even on Jesus himself. "Other Early Christian Gospels" collects all the recently-recovered Greek manuscripts containing parts of long-lost early Christian gospels into a single volume.;It includes new critical editions, English translations, and exhaustive indexes of the Greek fragments of the "Gospel of Thomas", the "Gospel of Peter", the "Egerton Gospel", and six other unidentified gospels. In addition, "Other Early Christian Gospels" features 'student's Greek texts' that present the restored Greek texts without any potentially confusing apparatus, editorial signs, or unidentifiable word fragments. This special student's version makes the fragmentary ancient texts dramatically more accessible to those still in the process of learning Greek.

Content list

1General Introduction;

2Editorial Method;

3Editorial Signs;

4Sigla;

5The Gospel of Thomas;

6Oxyrhynchus Papyrus 654 (POxy 654);

7Oxyrhynchus Papyrus 1 (POxy 1);

8Oxyrhynchus Papyrus 655 (POxy 655);

9The Gospel of Peter;

10Oxyrhynchus Papyrus 4009 (POxy 4009);

11The Akhmim Fragment (PCair 10759);

12Oxyrhynchus Papyrus 2949 (POxy 2949);

13The Egerton Gospel;

14Egerton Papyrus 2 (PEgerton 2) with Cologne Papyrus 255 (PKoln 255);

15Other Unidentified Gospel Fragments;

16The Faiyum Fragment (PVindob G 2325);

17Merton Papyrus 51 (PMert 51);

18Oxyrhynchus Papyrus 210 (POxy 210);

19Oxyrhynchus Papyrus 1224 (POxy 1224);

20Oxyrhynchus Parchment 840 (POxy 840);

21Berlin Papyrus 11710 (PBerol 11710);

22Bibliography;

23Indexes;

24Plates.

Wednesday, July 12, 2006

Not a Marcionite Manuscript

In an earlier post (here) I outlined the argument of Claire Clivaz that P69 (P. Oxy 2383) should be regarded 'as a witness to a Marcionite edition of Luke's Gospel' (C. Clivaz, 'The Angel and the Sweat Like "Drops of Blood" (Lk 22:43-44): P69 and f13' HTR 98 (2005), 419-440, citation from p. 420).

Here are some critical reflections on her argument.

Firstly, we should admit that the argument that P69 represents a Marcionite version of Luke (stated on p. 420; suggested on p. 429, 432, restated in conclusion, p. 439), is presented by Clivaz as a suggestion (p. 429), a proposal which offers a plausible fit for the peculiar nature of the text represented in P69. There is an appropriate hesitancy in her presentation of this argument.

Secondly, we need to note that by the nature of the evidence Clivaz’s argument is both difficult to prove and difficult to falsify. Marcion’s text of Luke cannot be determined with confidence for several reasons: no text survives; church fathers were not interested in providing Marcion’s text, but in refuting Marcion from his own text where possible. The primary characteristics of Marcion’s text are determined mostly be omissions and absences (minuses). Clivaz has to make an argument for Marcion’s likely text of this section of Luke and then (lo and behold) identify agreement in this minus between P69 and Marcion. So in effect it is a very complicated argument from silence.

Thirdly, perhaps simply stating the previous point a bit more strongly, there is no actual positive ancient evidence for ANY connection between Marcion’s text and P69.

Fourthly, P69 generally exhibits a pretty free or paraphrastic text (with numerous singular readings, numerous agreements with D although clearly independent of that type). Although Marcion does seem to have paraphrase occasionally as well as omitted material, there is no suggestion of a connection between Marcion’s text and the D-type text elsewhere (I stand to be corrected on this point). Focusing on two aspects of P69 without considering the wider evidence of P69’s text may have led Clivaz astray (ironically enough considering the amount of space given in pp. 425-426 to criticising others who have failed to reckon sufficiently with this manuscript).

Fifthly, in relation to P69’s text of Luke 22.61 Clivaz takes it as significant that Jesus is not looking at Peter, but that Peter is looking (p. 431). This she takes as avoiding the idea that Jesus paid attention to Peter, which fits with the supposedly Marcionite idea that Peter’s status would be diminished. Each of these steps are problematic.

- P69 doesn’t contain the required verb ‘look’ in its extant text. It does contain the last four letters of STRAFEIS followed by O P and traces which are plausibly reconstructed as PETR[OS, so there is clearly an implication that Peter turns, but no explicit indication that he looked. Clivaz appeals to the agreement of Turner and Comfort in reading ENEBLEPSEN in the gap, but this is not really an argument at all. We simply do not know what verb may have stood after PETROS and in a short manuscript which such a free text (several singular readings) we cannot simply assume something is there in order to prove a connection with another text.

- Furthermore, there is no actual evidence that Marcion’s text read ‘Peter looked at him’. Indeed there is no ancient evidence that Marcion’s text contained anything of Luke 22.49-62. As Clavez notes, Epiphanius specifically notes that Marcion’s Gospel lacked the section about Peter and the ear of the high priest’s servant (p. 432 note 94). But she fails to note that there is no positive evidence for the presence of the following section (52-62) in Marcion’s version at all. The second page of P69 contains material that is not attested in Marcion (on p. 431 note 92 such a position is taken by Clivaz as evidence of Marcionite omission of material; she doesn’t register the inconsistency in her argument).

- Clivaz attempts to show that the reconstructed text of P69 at Luke 22.61 can be read in a Marcionite manner as undermining Peter’s status because ‘Jesus cannot bear to look at him’ (p. 432). This may well be an imaginative reading, but doesn’t correspond to the normal Marcionite practice which she uses to illustrate the situation here: the omission of material that doesn’t fit with the Marcionite profile (see p431 note 92, which seems to assume re Luke 22.32 and 23.49 that since ‘neither passage is attested in Marcion’ that is evidence of Marcion deleting this material).

Sixthly, a good deal of Clivaz’s case rests on the argument that a scribe, troubled by apologetic difficulties, may have deleted 22.42 by strategy of "negating the objections" by omission; and that this strategy ‘would be practical only in a type of Christianity that preserved a single gospel, as did Marcion.' (p. 429). I don’t see this argument as having much force. Firstly, there is no other evidence for the omission of 22.42 in the textual tradition of Luke. Secondly, there are practically no scribal practices that work consistently over the whole four gospel canon. Thirdly, the evidence (especially from Oxyrhynchus) shows decisively that the gospels were copied predominantly individually right through until the fourth century. Thus the particular connection to a Marcionite redaction doesn't follow. Perhaps we should also note that we have no other evidence of Marcionite material from Oxyrhynchus.

In conclusion I think the suggestion that P69 is a manuscript of Marcion’s Gospel is a very clever idea which is however not proven and not the most plausible context for making sense of this fascinating manuscript.

70 vs 72 disciples

Monday, July 10, 2006

Activities at the Complutensian University

Pablo Torijano Morales, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Andrés Piquer-Otero, University of California-Berkeley and Juan-José Alarcón

"Text-critical Value of Secondary Versions in the Study of The Septuagint 3-4 Kingdoms"

Abstract

"This joint presentation attempts to illustrate the methodology for the treatment of some of the secondary versions of LXX in the context of providing text-critical data for the edition of the Göttingen Septuagint of 3-4 Kingdoms. The focus will be placed on the interest of the Armenian and Georgian versions and their relationship with issues in the history of the Greek text, namely the possible affinities with L (Lucianic) readings. Other versions whose connection with L has been traditionally studied (Old Latin) will also be considered. This global approach will try to explore the possibilities of isolating proto-Lucianic (and hence perhaps Old Greek) readings and will also relate them with other versions, both of LXX (Coptic) and of the supposed proto-M sphere (Targum, Peshitta, variants in Medieval Hebrew manuscripts). The analysis will comprise samples from kaige and non-kaige sections of the Books of Kings, therefore exploring the applicability of the Lucianic text (with the support of other versions) as a witness of Old Greek. The treatment and assessment of the textual problems and cases outlined in this presentation has benefited from a column-based synoptic approach to the texts, together with color codes which give face-to-face description of textual phenomena between the versions. Therefore, this paper and the ongoing research summarized in it underlines the importance of the secondary versions, presented in a polyglot approach, for the understanding of the history of the Biblical text."

This group appears to be working towards a critical edition of the text in a number of languages (including Armenian and Georgian). I have not been able to locate much more about their work online though this page suggests that the work may be nearly at an end. I'd be grateful for details of any more written information on this project.

Welcome to Randall Buth

Randall's publications cover many areas including linguistic, textual and exegetical matters in both testaments.

Saturday, July 08, 2006

Isaiah 53:5: canon and text issues

What would it mean to accept the MT as a canon?

I have a nice example for illustration. Most might follow the LXX in this example and would not think that the MT would need a footnote, even when going against the MT.

Isaiah 53:5 has an interesting reading in the MT uvaHavurato

ובחֲבֻרתוׂ 'and in his joining, in his group'.

Translations and even Hb lexica (!) will list this as "bruise, weal, wound, 'stripe'". However, in Hebrew that word would be uvaHabburato

ובחַבּרתו

I read the MT as distinct and different from the "wound" reading. Of course, the LXX and 1Pet read according to a "wound"-tradition: τω μωλωπι.

If I were reading an unvocalized text here, I would go with the "bruise, wound" reading, Habbura, like the LXX and 1 Peter.

However, I do not believe that that is the MT reading. If I were going to present the MT reading, I might translate as "we are healed in association with him".

I would happily footnote, even "demand" a footnote, along the lines of "we are healed by his wound, according to old Greek and a different vocalization of the Hebrew."

The point here in this post is that the MT is a distinct textual entity and should be respected on its own right. In addition, one may argue that this is a canon. It is certainly a canon within the synagogue.

blessings

Randall

Text and Canon, or, Do we really want an eclectic Hebrew Bible?

שלום חברה

This is a first post to the ETC and hopefully will appear in full if I don’t push the wrong buttons along the way.

There is a theoretical textual question that might be nice to discuss with this group. It is visible with the Hebrew Bible. Most Bible translations and many a commentary assume an unpublished, eclectic Hebrew text (whether they realize it or not) when translating/explaining the Hebrew Bible.

Do we want a new, 21st century eclectic text for the Hebrew Bible?

As a Bible translator I had assumed that a translator’s job included establishing a Hebrew text. It’s what everyone does and what most training directs and presupposes. It is the practice of every published Bible if there are footnotes along the lines of “according to LXX, Hebrew unclear”, or “according to different vocalization, Hebrew reads ‘xxxxx’”.

Some time ago [OK, 15 years already :-) ] I came to the conclusion that we don’t have enough background to produce a definitive pre-massoretic text of the Hebrew Bible. This is not a counsel of despair, but a recognition that the MT is in many respects a very conservative eclectic text with roots to the first century CE. If we accept it as a canon, we can translate it, and footnote our speculations and comparisons with other traditions. (Or, conversely, someone might use an LXX as their canon, and footnote MT differences and speculations outside the text.) Again, without realizing it, this is scholarly practice, where Leningrad is published in the BHS and everything else is footnoted.

Why don’t we acknowledge this and produce translations accordingly? It would mean defining the canon as the MT (or perhaps an LXX for some groups) and relegating all textual questions to “extra-canonical” footnotes.

I’ll give an example in another post on Is53 5 uvaHavurato ובחברתו.

blessings

Randall

Tuesday, July 04, 2006

A Manuscript Witness to a Marcionite edition of Luke?

If this could be substantiated it would be a major discovery, since hitherto we have no actual manuscripts of any of Marcion's works. The contents of Marcion's canon has to be (re-) constructed from the comments of his polemical opponents (esp. Tertullian and Epiphanius, but also others). [For some kind of introduction to Marcion's Gospel see my article on Marcion]

Clivaz makes the following points:

- P69 lacks Luke 22.42-45a

- This reflects a 'conscious omission' since 22.42-45a is a logical narrative unit

- Jesus' request that the cup pass from him (v42) was the most shocking element in the Gethsemane story (for ancient readers, as seen in Celsus; Porphyry, Origen)

- Celsus argued that some Christians had corrupted the text of the Gospels in order to evade the criticisms of opponents (Contra Celsum II.27 with specific reference to this passage)

- This could mean that scribes were omitting material from the Gethsemane account.

- 'This strategy of "negating the objections" by omission would be practical only in a type of Christianity that preserved a single gospel, as did Marcion.' (p. 429).

- Nothing of Luke 22.42-44 is attested in Marcion's Euaggelion (an argument from the silence of Tertullian and Epiphanius, with the authoritative support of Harnack)

- The omission of v42 is congruent with Marcionite Christology

- At Luke 22.61 in P69 Peter (not Jesus) is looking. This avoids any suggestion that Jesus is paying attention to Peter and is coherent with Marcion's avoidance of anything that could magnify Peter's status.

It is an interesting proposal. But can it stand up to critical scrutiny?

Monday, July 03, 2006

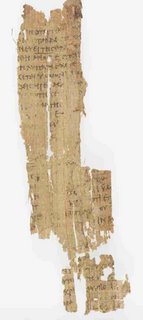

Glasgow, MS Gen 1026/13.

It is important as being one of very few early NT mss written in roll format (rather than codex). The larger piece has a rather badly preserved text for the most part, so I shall have to return next year for a closer look at the blanks!

Here are some pictures (Glasgow University Library has images of all their Oxyrhycnhus Papyri available here).

When did the Psalm titles get smaller?

I'm wondering when exactly this practice began. I've seen it in the facsimile edition of the Geneva Bible (1560), but presume it goes back before then.

What precedents there are for this in the manuscript tradition and in early printed editions (English, Latin, etc.)? I would guess that, while there might be a few analogies for this within mss, manuscripts would more generally have other ways of marking titles (e.g. colour of ink) since a slight change of character size is hard to achieve in a ms.

It seems to me that to use another font, character shape, colour or italics for the titles can usefully separate them from the rest of the text, but that if you print them in a smaller size it will almost inevitably be seen as giving them a lower status.

A few translations, of course, do not give the titles at all (e.g. NEB). Was Coverdale also thus (modern spelling edition here)?