Tuesday, January 31, 2006

Designing a Greek New Testament

There is a need for a manual edition that is more focussed on the question of the original text. This would begin to highlight where true uncertainty exists and would allow researchers to focus attention on those parts.

Despite the level of abbreviation that takes place in the apparatus of NA27 it still generally considers variants as whole words. I should like a system that is more willing to pinpoint the variation by letters. Thus, if ° were allowed to apply to single letters within a word,

πιστευ°σητε

could signal the variation in John 20:31 most succinctly, provided the ° could be placed in a way that did not interrupt the flow of the text. Nor is there any particular reason why ╭ ╮ should not occur in the middle of a word.

Monday, January 30, 2006

The E-Commentary Project

I have received the following announcement from Andrew Wilson:

The E-Commentary Project

Anyone dissatisfied with the thin gruel of theoretical minutiae and wanting to get their teeth into the tasty bits of textual praxis is welcome to join the E-Commentary Project.

For a short summary of the E-commentary project go to www.nttext.com/nttop.html. For a fuller statement of the idea behind the commentary and its principles, see the General Introduction at www.nttext.com/commintro.html. The actual commentary discussion will be located on the Forum at http://www.nttext.com/forum

This year, it is envisaged tackling some evangelical favourites: Galatians, Romans, 1 and 2 Corinthians, one chapter per week commencing in March.

In preparation for Galatians, there is also a study posted on the Forum about Scribal Habits in Galatians, analysing the singular readings of all of the MSS in Swanson's Galatians volume. There is also a review of Moises Silva's study of Scribal Habits in Galatians (in the Scribes and Scriptures volume).

Anyone who thinks they might be interested in participating is welcome to register on the Forum and participate in discussions.

Saturday, January 28, 2006

Mark D. Roberts on Ehrman

Earlier comments: here.

Ecumenical project 2

If we're looking for scholarly contribution, I'd say that the groups most likely to have the calibre of scholar we would need would be the RC and the Greek Orthodox churches. Armenian Orthodox, being a group with scholarly tradition based within an independent country, might also be well resourced. However, on OT matters Orthodox groupings tend to be committed to a text quite deviant from the Hebrew, but which is not the 'Old Greek' of the 'LXX' either. So for the sake of argument we might confine co-operation to the NT. Obviously co-operation with the Greek Orthodox would be a natural thing for evangelicals committed to 'Byzantine-Priority' or Majority Text theories. We've already seen a common interest between certain groups of evangelicals and the Greek Orthodox with the production of The Orthodox Study Bible using the NKJV (let's not talk about the textual basis for that!).

What jobs could best be done with such wide co-operation? I suppose that one might be able to launch a major academic project taking apart some of the more cynical reconstructions of early Christians and their treatment of the text. One might also be able to co-ordinate response to books (or other media) that seek to discredit the integrity of Christian scripture (e.g. the likes of that code book by Dan someone or other). Anything else?

Seeds planted

Friday, January 27, 2006

Caragounis on pronunciation of Greek

Thursday, January 26, 2006

Theodore Letis

Jim Leonard has drawn my attention to the page Theodore P. Letis in Memorium [sic], a tribute to an ecclesiastical historian who wrote controversially on matters relating to textual criticism. He died last year in a car accident returning from a gig. There seem to be varied interpretations of what his position was. He could be seen as KJVO, Majority Text, anti-inerrancy, Childsean—categories that do not usually appear alongside each other. He was highly idiosyncratic and it seems that during the last decade of his life he espoused views that he would not have held earlier. I met him in Tyndale House, Cambridge, a few years ago, and had been previously convinced that he was basically an up-market KJVO advocate. However, if I understood our conversation correctly—and he seemed to enjoy mystifying—he basically accepted a fairly standard history of the text during the first four centuries, but believed that what the text that the church had come to receive was the locus of authority. For instance, he thought that Mark 16:9-20 was secondary and inspired. He was aware that some of his conservative constituency did not realize that his position involved this.

Jim Leonard has drawn my attention to the page Theodore P. Letis in Memorium [sic], a tribute to an ecclesiastical historian who wrote controversially on matters relating to textual criticism. He died last year in a car accident returning from a gig. There seem to be varied interpretations of what his position was. He could be seen as KJVO, Majority Text, anti-inerrancy, Childsean—categories that do not usually appear alongside each other. He was highly idiosyncratic and it seems that during the last decade of his life he espoused views that he would not have held earlier. I met him in Tyndale House, Cambridge, a few years ago, and had been previously convinced that he was basically an up-market KJVO advocate. However, if I understood our conversation correctly—and he seemed to enjoy mystifying—he basically accepted a fairly standard history of the text during the first four centuries, but believed that what the text that the church had come to receive was the locus of authority. For instance, he thought that Mark 16:9-20 was secondary and inspired. He was aware that some of his conservative constituency did not realize that his position involved this.The tribute is followed by comments from someone who knew him exclusively as a blues musician. It seems that he kept is identities somewhat separate. (“... we knew him as a swaggering front man who liked Muddy Waters and The Stones above all else in life.”)

Further links on Letis can be found on:

http://www.holywordcafe.com/bible/Letis.html

and

http://www.kuyper.org/thetext/

The second link in particular, which gives no indication of Letis’ death, suggests that there may be some work to do bringing Letis’ intellectual legacy into order.

I discovered the authoritative pronunciation of his name as Lee-tiss when I experienced his strong reaction as I tried to order a taxi for him using the pronunciation Lettuce.

I have not read widely in the Letis corpus; I tended to be disappointed by what I read. I should therefore be interested to know if anyone formed a more favourable opinion of what he had to say.

Update (3/13/18)

Here is video of LetisTuesday, January 24, 2006

Review of Robinson and Pierpont

Review of:

Review of:The New Testament in the Original Greek: Byzantine Textform, 2005, compiled and arranged by Maurice A. Robinson and William G. Pierpont (Chilton Book Publishing: USA, 2005).

Anyone who manages to bring a Greek New Testament all the way to publication deserves congratulation. A vast amount of work must have gone into producing this beautiful edition, which now contains accents, breathings, punctuation, and capitalization (see previous post).

It has an extraordinarily enlightened copyright policy:

'Anyone is permitted to copy and distribute this text or any portion of this text. It may be incorporated in a larger work, and/or quoted from, stored in a database retrieval system, photocopied, reprinted, or otherwise duplicated by anyone without prior notification, permission, compensation to the holder, or any other restrictions. All rights to this text are released to everyone and no one can reduce these rights at any time. Copyright is not claimed nor asserted for the new and revised form of the Greek NT text of this edition, nor for the original form of such as initially released into the public domain by the editors...Likewise, we hereby release into the public domain the introduction and appendix which have been especially prepared for this edition.' (reverse of title page)

The edition seeks to present as faithfully as possible the New Testament in the Byzantine textform, which the compilers also believe is exceedingly close to the original text of the New Testament.

The editors' preference for the Byzantine textform notwithstanding, there are several reasons why this edition is of significance to those who do not adhere to the so-called Byzantine Priority position:

1) It lists all variants between the Byzantine text (as given by the editors) and the Nestle-Aland text. This is the first time that this has been done and it allows one to begin to judge the nature of the Byzantine text in a more systematic way than was previously possible.

2) By its focus on the Byzantine text, this edition highlights certain interesting variants that are not even given in manual editions of the Greek New Testament.

3) Robinson has collated all mss of the Pericope Adulterae. The textforms given here for that passage are therefore uniquely authoritative. In the book of Revelation some information can be gained from this edition that cannot readily be gained from other manual editions—for instance, the identity of passages where there is strong support for the use of Greek letters as numbers and the identity of passages where there is no widespread use of letters in this way.

The 23-page preface explains the rationale for the edition, introduces its layout and concludes with a strongly theological section. In this the editors affirm (after the Westminster Confession) that divine revelation 'has been kept pure in all ages by the singular care and providence of God' (p. xxi). They particularly relate this providence to preservation of evidence. 'The task set before God's people is to identify and receive the best-attested form of that Greek biblical text as preserved among the extant evidence. Although no divine instruction exists regarding the establishment of the most precise form of the original autographs, such instruction is not required: autograph textual preservation can be recognized and established by a careful and judicious examination of the existing evidence. Scribal fidelity in manuscript transmission over the centuries remains the primary locus of autograph preservation' (loc. cit.).

The work closes with an appendix by Robinson, entitled 'The Case for Byzantine Priority', justifying the approach underlying the edition. This has appeared previously in TC: A Journal of Biblical Textual Criticism 6 (2001). This appendix does not contain the explicity theology of the Preface, though it does distance the Byzantine Priority position from approaches that seek to relate 'providential preservation' to a particular Greek text.

It is not possible here to engage with the Byzantine Priority hypothesis underlying this edition, except to make a few brief remarks:

It is clear that Robinson has considerable admiration for Westcott and Hort. He even claims that the Byzantine Priority school is 'more closely aligned with that of Westcott and Hort than any other' (p. 539). He naturally thinks that their biggest mistake was their theory of a fourth century Syrian recension. Robinson challenges this notion, and in doing so is in the company of a great many critics. Having rejected a Byzantine recension, it is then rather striking that Robinson opts for an Alexandrian recension: 'the Alexandrian text of the NT is clearly shorter, has apparent Alexandrian connections, and may well reflect recensional activity' (p. 542). Let proponents of the Byzantine text not be so like the unforgiving servant (Matthew 18:23-35)!

A general rule for use of evidence is that big claims require big evidence. Any claim for widespread recensional activity in the early Alexandrian text therefore requires a considerable amount of evidence, but this is lacking. Robinson does footnote one article of his in support: 'The Recensional Nature of the Alexandrian Text-Type: A Response to Selected Criticisms of the Byzantine-Priority Theory', Faith and Mission 11 (1993 [actually published 1997]) 46-74. I have not read this article, but if it does support something as significant as the author claims then it surely ought to be made available in a more widely circulated journal or on the Internet.

Robinson gives a range of arguments in support of Byzantine Priority. One that will be considered here is his claim that the sequential result of eclectic reasoning rarely has support in the manuscripts when an extended length of text is considered. Now it is obviously possible to suggest scenarios whereby manuscripts would contain a mixture of original and secondary readings, making it necessary for critics to restore the original by an eclectic process. However, the more substantial question raised by Robinson's argument is one of the probability of various eclectic solutions. It is clear that most of us textual critics have an eclectic approach but that we do not even contemplate calculating the levels of complexity involved in possible routes whereby our reconstructed text could have given rise to the particular distribution of readings we see in the manuscripts. Given that the number of copying generations between our earliest manuscripts and the original is more likely to be in double figures than in triple figures, we should probably still expect sequences of readings of the original to be grouped together to some extent within extant witnesses. This is obviously an area that requires further analysis.

Although it may be that eclectics do not consider enough the transmissional process implied by their choice of readings, Robinson's solution to reject all forms of eclecticism seems an unnecessary response. His aversion to eclecticism means that he in fact prints two versions of the Pericope Adulterae rather than select between the readings of different manuscript groups. Thus von Soden's μ5 group is printed as the main text and his μ6 group as an alternative in an italicized footnote. Since eclecticism is not allowed in any form then Robinson cannot even consider abandoning the Byzantine text when it is at its most isolated. The bottom line in the Byzantine Priority position as here outlined is that no matter how much support there is for a reading outside the Byzantine tradition it cannot be conceived of as original without wide Byzantine support.

It is clear that the basic textual philosophy of this edition is not going to change in response to the views of those who cannot accept the Byzantine Priority position. However, even while remaining true to the compilers' textual theories, this edition could be improved in a number of ways.

1) A minor point from an academic perspective, but a major point from a user's perspective is that the edition is rather bulky. While the size of type-face certainly has some advantages (e.g. for the visually impaired) this is far too large for those of us who like to slip a Greek New Testament into our pocket. We already sometimes experience difficulty with the size of the Nestle-Aland 27th edn, which is larger than the 26th, which in turn was larger than the 25th. Robinson and Pierpont's edition is more like the size of a street preacher's Bible and its dimensions could easily be reduced.

2) More significantly, many readers will have considerable trouble with the fact that nowhere are any manuscript witnesses cited. Given Robinson's critique of eclectic editions for producing a text with no support over a section of any length in any single manuscript, it is important for Robinson to show that his edition does indeed have the support of manuscripts. While the Preface (pp. ix-x) assures us of its support within the bulk of Byzantine manuscripts, scholars are naturally sceptical, and it would be a great help if, alongside the claims of the Preface, the edition could list specific manuscripts in its support. There is some precedent for doing this in the UBS Greek New Testament's representation of the Byzantine text by giving select witnesses within brackets. Some similar way should be found of confirming the close relationship between this text and actual manuscripts.

The edition may be ordered as follows:

The publishers are Chilton Publishing. Their webpage links to Amazon, where the title retails for $17.95.

Prof. Robinson writes:

'I hope it soon will be available from CBD (Christian Book Distributors) at a discount from retail, perhaps selling at around $13. The publisher (Chilton) is willing to ship case lots of 12 at the lowest possible price (around US$7-8 per copy with shipping additional), but he is not equipped to ship individual copies. On the other hand, I am willing to ship individual copies within the US for $11 (which includes postage and handling).' (private e-mail)

Justin Martyr conference, Edinburgh

Ehrman, Peter, Paul, and Mary Magdalene

From OUP website:

'Bart Ehrman, author of the highly popular Truth and Fiction in The Da Vinci Code and Lost Christianities, here takes readers on another engaging tour of the early Christian church, illuminating the lives of three of Jesus' most intriguing followers: Simon Peter, Paul of Tarsus, and Mary Magdalene.

What do the writings of the New Testament tell us about each of these key followers of Christ? What legends have sprung up about them in the centuries after their deaths? Was Paul bow-legged and bald? Was Peter crucified upside down? Was Mary Magdalene a prostitute? In this lively work, Ehrman separates fact from fiction, presenting complicated historical issues in a clear and informative way and relating vivid anecdotes culled from the traditions of these three followers. He notes, for instance, that historians are able to say with virtual certainty that Mary, the follower of Jesus, was from the fishing village of Magdala on the shore of the Sea of Galilee (this is confirmed by her name, Mary Magdalene, reported in numerous independent sources); but there is no evidence to suggest that she was a prostitute (this legend can be traced to a sermon preached by Gregory the Great five centuries after her death), and little reason to think that she was married to Jesus. Similarly, there is no historical evidence for the well-known tale that Peter was crucified upside down. Ehrman also argues that the stories of Paul's miracle working powers as an apostle are legendary accounts that celebrate his importance.

A serious book but vibrantly written and leavened with many colorful stories, Peter, Paul, and Mary Magdalene will appeal to anyone curious about the early Christian church and the lives of these important figures.'

Monday, January 23, 2006

An ecumenical project ...

Friday, January 20, 2006

Study papyri in Italy

CENTRO DI STUDI PAPIROLOGICI-LECCE UNIVERSITY

SCUOLA ESTIVA DI PAPIROLOGIA-TERZA EDIZIONE

(Lecce, 3rd-8th July 2006)

The Centro di Studi Papirologici of Lecce University is organizing the Third Edition of the Scuola Estiva di Papirologia that will take place from July 3rd to July 8th 2006.

The School is open to graduates and last-year undergraduates in Classical Studies and to PHD concerned with the deepening of the main topics of Papyrology, such as the contribution of the papyri to the history of Greek and Latin Literature; the history of Greek and Latin writings; the reconstruction of ways and forms of book production and circulation in the ancient Mediterranean area; the study of Graeco-Roman Egypt; the Herculanean Papyri; the Medical Papyri; Papyri and digital Technology.

Moreover, transcription exercises of Greek and Latin documentary and literary papyri are expected.

Only a limited number of participants will be admitted to the courses.

Anyone interested in the School should send the application, a curriculum vitae and a teacher's reference to the Centro di Studi Papirologici by mail or e-mail. The deadline for the final application will be March 31st 2006.

A fee of € 210 will be paid in May 31st 2006.

For further information please contact the Centro di Studi Papirologici

Lecce University

Via V.M. Stampacchia, Palazzo Parlangeli

I-73100 Lecce (Italy)

Tel: 0039-0832-294606

Fax: 0039-0832-294607

E-mail: cspapiri@ilenic.unile.it

Posted from the Papy-list

Thursday, January 19, 2006

A nice-looking, free Greek font...?

'I have obtained from Maurice Robinson the latest text files with the accented 2005 Byzantine Text. I plan to put up a web viewable/searchable version of the Byzantine text (including the parsings provided by Dr. Robinson). I initially planned to use Mounce's Teknia Greek font, but the more I look at it, I see that it's not going to be good enough. Do you have any recommendations for a nice-looking, free Greek font to use with this project?'

My shopping list would be: nice-looking and free and Unicode...

Date of P52

Play it again[, Sam]

This seems to me to be a questionable supposition since there is often a strong oral tradition of citation that is independent of the what is written in copies of the scriptures.

I'm looking for examples, ancient or modern, of the phenomenon whereby, as in Casablanca (see title of this post), the way something is regularly cited is divergent from the original.

From the Rime of the Ancient Mariner we have:

'Water, water every where, and not a [original: Nor any] drop to drink.' (9,400 Google hits)

From the Bible we have:

'helpmeet' (Gen. 2:18; 'meet' belongs with the following phrase, i.e. 'meet for him')

and

'Our Father who [KJV: which] art in heaven'—has any Bible ever printed 'who art'?

There is also the case of the 'Rich Young Ruler'.

How common is this phenomenon? How common was it in the Patristic period and what criteria could we use to find out?

Wednesday, January 18, 2006

Stanley Porter, the Book of Acts, and Textual Criticism

MB: Dr. Porter, you mentioned at your recent SBL presentation at the Acts seminar that there was little point writing a commentary using the NA27 or UBS4 editions, since the reconstructed texts do not correspond to any extant manuscript. Do you think that it is more viable to write commentary on Acts using the Alexandrian or even the Byzantine text-type as a "template"?

Did I say “little point” regarding the Nestle-Aland or UBSGNT? I think that it is fine to write a commentary on this text, but it would perhaps be more valuable as a commentary on nineteenth- and twentieth-century scholarship, especially German textual criticism, than it would anything else. In fact, this might be quite interesting. However, it would still leave us at a significant remove from the earliest text of Acts. That is why I raised the issue in my paper of whether a commentary that purports to be one on the Greek text of Acts is actually doing justice to this notion by using the Nestle-Aland or UBSGNT text. I think that a better option—if one wants to get closer to the original—is to use one of the early complete manuscripts, such as Vaticanus or Sinaiticus, perhaps supplemented by the early papyri. My contention is that despite the scholarly claims of some textual critics, we do not get closer to the original (and, if rightly defined, I do believe that the notion of an original text is a useful and even necessary one for most purposes) by studying an eclectic text. We get closer when we begin with an early complete manuscript that was actually used in ancient Christian communities. In one sense, I do not agree with you that simply commenting on a text-type is more viable—even if the Nestle-Aland and UBSGNT, so far as I have been able to determine, are based upon the Alexandrian text type and could be considered one of these. What I am arguing is that we should go back to actual early manuscripts. In that sense, commenting on a Byzantine manuscript would also be a viable option in some ways, although, with all due respect to my friends who argue for this text, I do not believe that any of these are as early as the major Alexandrian manuscripts, especially when Acts is concerned. I reject the various theories regarding the Western text of Acts that see it as early as the Alexandrian.

MB: This goes against the trend in recent commentaries that simply assume NA27 or UBS4. What made you come to this conclusion?

My position on this came about through a variety of means. One was on-going seminar discussions with students and faculty colleagues when I taught in the UK. A second was noticing that Hebrew Bible studies and Greek New Testament studies proceed along different lines, with Hebrew Bible studies utilizing single manuscripts. If they can use a single manuscript as the basis of their textual criticism, and that manuscript is around a millennium removed from the actual composition of the text, then I thought that perhaps we should use the Greek manuscripts, especially as they are much closer to the date of composition. A third was my own work in papyrology, where I was involved for some time in studying and editing a number of Greek manuscripts of the New Testament, and, along with my wife, had the privilege of publishing a sixth-century fragment of the book of Acts. A fourth would be my concern for the Bible as a product of and fundamental document within the Church. I concluded that it was more important to comment on actual documents that were used by early Christians than later eclectic texts that never had a home in the Christian Church.

MB: Have commentary writers become too dependent upon Bruce Metzger’s A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament? If so, how can this be avoided?

I have been somewhat surprised but mostly disappointed that most commentators, even those who are commenting on the Greek text, show very little attention to matters of language, and only slightly more interest in matters of textual criticism. The comments made and the choices regarding readings are often not well considered, and are usually confined to the choices presented in the apparatus of the eclectic Nestle-Aland or UBSGNT texts. I am not sure that commentators have come to be too dependent upon Metzger’s textual commentary. The pattern that I note is that commentators look at what their standard eclectic text offers and usually agree with it—sometimes citing Metzger in support. I would simply repeat what I have said above, and that is that if scholars were more familiar with particular manuscripts they would be forced to compare and use them in a fresh way.

MB: The text of Acts represents a whole host of text-critical problems, especially the differences between the Western and Alexandrian texts. What do you think is the best way of accounting for this divergence in the witnesses of Acts?

There is certainly a whole host of text-critical problems if one counts them individually. As I work through the text of Acts, it seems to me that many of them are focused around the difference between the so-called Alexandrian and Western traditions. That is typically represented as the difference between our standard eclectic texts and Codex Bezae (D). When I first started working on my commentary, one of my first tasks was to investigate these two textual traditions, and I concluded that the so-called Western tradition was later and probably a form of interpretation of the Alexandrian. I am thus concentrating on commenting upon the Alexandrian tradition, referencing the Western in terms of interesting later interpretations that it presents, rather than as a competing concurrent primary text.

MB: W.A Strange The Problem of the Text of Acts (SNTSMS 71; Cambridge: CUP, 1992) theorizes that Luke left Acts unfinished at his death, and that Acts was posthumously completed and published by editors who performed independent revisions of the text. Are such theories helpful or needlessly speculative?

I may conclude differently when my commentary is done, but I don’t think that such explanations are particularly helpful. In some cases, they seem more designed to reinforce critical orthodoxy (e.g. around a projected date of composition of Acts), rather than emerging from the text itself. I would argue that Acts is what it appears to be, an account of the events that the author knew up to the time of writing. Acts does not appear to me to be a work cut off in mid-stride, but one that wrote to the extent of the author’s knowledge. If this is the case, then I think that this has implications for the date of composition of Acts (it is early, that is, before Paul’s death), and by further implication for the date of composition of Luke’s Gospel. There are a number of potential further implications, such as theories regarding synoptic dating and origins, but I am not going to let these dictate what I find in Acts. I would note that there are some who recognize an early date for the writing of Acts but who might posit a later edition or re-edition of Luke’s Gospel, and thus have later dates for the synoptics and their development.

MB: What contribution can discourse analysis make to textual criticism?

The role of discourse analysis for most areas of New Testament study is greatly underdeveloped and underemployed. I am encouraged that there are a few scholars who are exploring the use of discourse analysis, although not all of them are using rigorous forms of it. I am an advocate of more rigorous and linguistically based models of discourse analysis being used for the study of the texts of the New Testament, and my commentary on Acts has some of these elements included in it (within the parameters of the series). Textual criticism would be one of the areas that discourse analysis could play a greater part. One of the major problems that I have encountered in textual criticism is the ad hoc nature of making text-critical determinations. The limited scope of our eclectic texts of the New Testament also ensures that we have limited numbers of variants, and no real appreciation of the text-critical characteristics of a single manuscript. I would see discourse analysis as providing potential insight into the character of given manuscripts on the basis of its particular readings. These discourse patterns can then be compared across manuscripts to help make text-critical determinations in particular instances.

MB: Out all the Acts commentaries available at the moment, which one would you recommend to seminary and university students for a concise study of textual issues relating to the Book of Acts?

I think that I would still recommend the earlier (2nd) edition of F.F. Bruce’s commentary on the Greek text of Acts. I know that there are those who criticize Bruce’s commentary for not having as much theology as they would like, but I take this as a stronger indictment of the critics than of Bruce. I believe theology is important, but it needs to grow out of our study of the texts, not be foisted upon them. I always find that Bruce is worth considering and surprisingly fresh and enlightening in his analysis.

Stanley E. Porter (Ph.D) is President, Dean and Professor of New Testament at McMaster Divinity College. He is writing a commentary on the Acts of the Apostles for the NIGTC series.

Tuesday, January 17, 2006

Our Bible and the Ancient Manuscripts (Kenyon)

BTW: There are also 32 plates ("illustrations") including a folio of P46 (of the Beatty portions) following the sequence of the Michigan just described in the previous post. This plate shows Gal 6:10-Phil 1:1, of course not near the same quality but anyway...

Images of P46 (Michigan portions)

Briefly this includes:

Fol. 16-17 = Rom 11.35-14.8

Fol. 19-28 = Rom 15.11-Heb 8.8

Fol. 30 = Heb 9.10-26

Fol. 40 = 1 Cor 2.3-3.5

Fol. 70-85 = 2 Cor 9.7 –end; Eph; Gal 1.1-6.10

Excellent work!

Up-date: this link doesn't work anymore, so I have found the entry in the Way Back Machine and paste some of the information in here (4.12.08). I have re-jigged the links so I hope that they work, but I haven't checked them all.

A New Way to Access Michigan's P46 Images

P46 is without question one of the most important manuscripts for New Testament studies, and arguably the most important text of the Pauline Corpus. The manuscript itself was comprised of 104 leaves strung together into a codex. Today 86 of those original 104 leaves are extant and housed in both Michigan and Dublin. The reason for its importance is that it is the earliest extant collection of Paul's letters. The usual date ascribed to it is 200 C.E., though Aland notes that there is leeway on either side (Text 87). The order of the contents of P46 is as follows: Romans, Hebrews, 1 Corinthians, 2 Corinthians, Ephesians, Galatians, Philippians, Colossians, 1 Thessalonians, and 2 Thessalonians. The Pastoral Epistles, in their present form, were not contained in P46 as there was not enough space on the remanding leaves for them to have been included. Most scholars claim that 2 Thessalonians was counted, despite the fact that it has not been preserved over the centuries. Parts of Romans and 1 Thessalonians are also missing. 1 Thessalonians, if I recall correctly, does not contain an alpha in the title, thus some have argued that 2 Thessalonians was never included because the collater of P46 only knew 1 Thessalonians as Paul's only letter to that group. Another issue with P46 is how it handles the doxology in Romans by placing it after Romans 15:33 and before chapter 16. P46 is generally categorized as belonging to (or preceding) the Alexandrian text-type, though there are some Western qualities about it.

As I mentioned above, part of P46 resides in Michigan at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. They possess thirty of the 86 leaves, which they have made availabe on their website (which I blogged about in August). I often refer to the APIS (The Advanced Papyrological Information System at U Michigan) website to look at the very detailed images of P46, yet their system is often very difficult to navigate. I finally took the time to list the contents of each of the leaves (front and back, thus sixty images) and link to them individually, which is what I have below:

3553 • Rom 11.36—12.8

3554 • Rom 12.10—13.1

3555 • Rom 13.2-11

3556 • Rom 13.12—14.8

3557 • Rom 15.11-19

3558 • Rom 15.20-28

3559 • Rom 15.29—16.3

3560 • Rom 16.4-13

3561 • Heb 1.7—2.3

3562 • Heb 2.11—3.3

3564 • Heb 2.3-11

3565 • Heb 3.3-13

3569 • Rom 16.14-23

3570 • Rom 16.23—Heb 1.7

3571 • Heb 3.13—4.4

3572 • Heb 4.4-14

3573 • Heb 4.14—5.7

3574 • Heb 5.8—6.4

3575 • Heb 6.4-13

3576 • Heb 6.13—7.2

3577 • Heb 7.2-11

3578 • Heb 7.11-20

3579 • Heb 7.20-28

3580 • Heb 7.28—8.8

3581 • Heb 9.10-16

3582 • Heb 9.18-26

3583 • 1 Cor 2.3-11

3584 • 1 Cor 2.11—3.5

3585 • 2 Cor 9.7—10.1

3586 • 2 Cor 10.1-11

3587 • 2 Cor 10.11—11.2

3588 • 2 Cor 11.3-10

3589 • 2 Cor 11.12-22

3590 • 2 Cor 11.23-33

3591 • 2 Cor 11.33—12.9

3592 • 2 Cor 12.10-18 (typo on APIS)

3593 • 2 Cor 12.18—13.5

3594 • 2 Cor 13.5-13

3595 • Eph 1.1-11

3599 • Eph 1.12-20

3600 • Eph 1.21—2.7

3601 • Eph 2.10-20

3602 • Eph 2.21—3.10

3603 • Eph 3.11—4.1

3604 • Eph 4.2-14

3606 • Eph 4.15-25

3607 • Eph 4.26—5.6 (typo on APIS)

3608 • Eph 5.8-25

3609 • Eph 5.26—6.6

3610 • Eph 6.8-18

3611 • Eph 6.20—Gal 1.8

3612 • Gal 1.10-22

3613 • Gal 1.23—2.9

3614 • Gal 2.9-21

3615 • Gal 3.2-15

3616 • Gal 3.16-29

3617 • Gal 4.2-17

3618 • Gal 4.20—5.1

3619 • Gal 5.2-17

3620 • Gal 5.20—6.8

He also wonders about whether 2 Thessalonians was in the original collection: "1 Thessalonians, if I recall correctly, does not contain an alpha in the title, thus some have argued that 2 Thessalonians was never included because the collater of P46 only knew 1 Thessalonians as Paul's only letter to that group."

This doesn't actually relate to a Michigan piece at all, but fol 94r (in Chester Beatty Library).

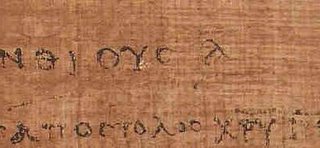

I think it is a bit of a stretch to say that the absence of a clear alpha is significant here, since it is a rather damaged piece, reading basically:

PROS [QESSALONEIK]EIS [A

Here is a scan:

It seems to me that the tiny trace is at least compatible with either the tip of the alpha or the bar (for comparison we need fol 38v (also Chester Beatty). Scan of the 1 Corinthians title (blown up a bit):

Monday, January 16, 2006

Old Syriac texts online

A Test in Emendation

Worrel, William H. "Fayumic Fragments of the Epistles." Societe de la Archaeologie Copte 7.

The description comes from: http://www.panikon.com/phurba/biblio.html

There are evidently quite a few problems with this bibliographical entry, including the author's name and mistakes in the French. I should be most grateful if someone would use text-critical devices or their own knowledge of the material to tell me what the publication details really should be, so that I can add it to my Coptic Bible Bibliography.

More on Misquoting Jesus

Other postings on Misquoting Jesus are:

Ehrman's Preferred Title, Dan Wallace Reviews Misquoting Jesus, Review of Bart Ehrman Misquoting Jesus, Further Reflections on Ehrman, Live and Late from SBL.

Sunday, January 15, 2006

How to write proper

Saturday, January 14, 2006

Boanerges and B(w)oston

Order your papyrus leaves here!

Truth and grammatical error

Wednesday, January 11, 2006

An Evangelical Bible Society

The advantage of an evangelical Bible society is that it also might be able to be a market force to counterbalance evangelical publishers. They each like to have their own translation since translations sell well. An evangelical Bible society would not be for profit and would be able to put pressure on publishers not to use Bibles as a source of profit.

The Trinitarian Bible Society was, originally, a mainstream evangelical Bible society, with a rather broad compass (e.g. Edward Irving). Its exclusive commitment to our beloved KJV has, however, meant that it can no longer serve the mainstream.

Thoughts?

Evangelical Textual Criticism

Tuesday, January 10, 2006

Wieland Willker's Online Textual Commentary

D, F, and G in the Pastorals

Monday, January 09, 2006

Carson in JBL

'Syntactical and Text-Critical Observations on John 20:30–31: One More Round on the Purpose of the Fourth Gospel'.

Ehrman's preferred title

'The title, btw, wasn't at all my idea. In fact, I was strongly against it. I wanted to call the book "Lost in Transmission."'

I suppose this just raises the question as to what exactly was lost. This title doesn't appear to fit the content of the work any better.

Previous comments here.

Saturday, January 07, 2006

Papyrus seeds or plant wanted

Friday, January 06, 2006

Accents in Robinson and Pierpont (final)

Thursday, January 05, 2006

Dan Wallace reviews Misquoting Jesus

Dan Wallace has now written a review of Bart Ehrman's Misquoting Jesus on the Aspire2 Blog. His review takes the subject from a different but complementary angle to mine. I limit myself to one quotation:

Dan Wallace has now written a review of Bart Ehrman's Misquoting Jesus on the Aspire2 Blog. His review takes the subject from a different but complementary angle to mine. I limit myself to one quotation:'Unfortunately, as careful a scholar as Ehrman is, his treatment of major theological changes in the text of the NT tends to fall under one of two criticisms: Either his textual decisions are wrong, or his interpretation is wrong. These criticisms were made of his earlier work, Orthodox Corruption of Scripture, which Misquoting Jesus has drawn from extensively. Yet, the conclusions that he put forth there are still stated here without recognition of some of the severe criticisms of his work the first go-around.'

God-given words and textual criticism

Verbal inspiration is not merely an evangelical concept, but one presupposed in OT phrases that speak of God’s ‘words’ (e.g. Ps. 119:130). This pre-Christian idea has at various times been embraced by a wide range of historic churches. In fact, verbal inspiration has proven such a powerful notion that it has even been attributed to translations of the Bible, e.g. the Septuagint, or part thereof (Philo, De Vita Mosis 2.37-38), Vulgate, and, in the last century, even the KJV. This of course raises the question of the extent of such inspiration. We should avoid multiplying unnecessarily entities that have been thus inspired. Protestants at the Reformation maintained that verbal inspiration applied to the Hebrew/Aramaic text of the OT and the Greek of the NT, and evangelicals have generally continued in the same belief. My questions are as follows:

1) What, according to textual criticism, are the principal problems with maintaining that the 39 + 27 books of the (Protestant) Bible are verbally inspired in the original languages?

2) What are the ways one might go about addressing these problems?